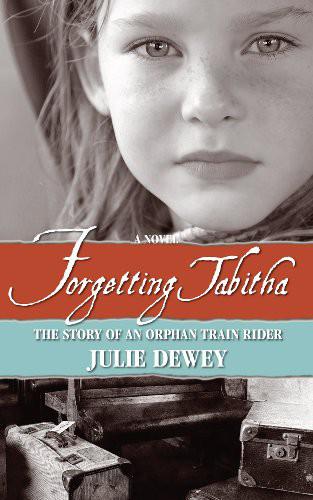

Forgetting Tabitha: An Orphan Train Rider

Read Forgetting Tabitha: An Orphan Train Rider Online

Authors: Julie Dewey

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #Retail

Chapter 5 Binghamton, New York

Chapter 6 Scotty in New York City

Forgetting Tabitha

The Story of an Orphan Train Rider

By Julie Dewey

Dedicated to my beautiful mother

Who never waivers in her support

Who has taught me to be a better person

Who has encouraged me to go after my dreams

Who has loved me unconditionally,

Thank you Mom!

“Happiness is not a destination, it is a way of life”

Copyright

© 2013 Julie Dewey, all rights reserved worldwide. No part of this book may be reproduced or uploaded to the Internet, or copied with out written permission from the author.

Thank you for respecting and supporting authors.

Prologue 1920

In my reverie now, an old lady settled in a creaking wicker rocker, amongst a bounty of lush gardens, I recall Mama’s stories about my birth and our early years both on the farm and in the city. I hear the whispers from yesterday, creeping backwards through time reminding me of who I am, where I came from, and how I came to survive my plight. Certain moments flutter by like the seeds from a dandelion blowing wishes in the wind, but others stand out and bear the weight of my shaping.

I close my eyes and remember our spread out farming days in the summertime, the gentle nuzzle of Oliver’s velvety nose as I fed him a juicy apple picked fresh from our very own tree. His soft mane and calm nature as he guided me through our pastures, always steady of foot. I ruminate over the harshness of many a winter, huddling together with Mama and Da by the fire to stay warm and sharing nettle tea to fill our trembling bellies in the lean months. But mostly I remember the spring, for that is when the daffodils and crocuses came to life, when the earth thawed and where Mama always began with my birth story.

My story begins amidst the wild meadow, I can see the landscape of budding flowers in my mind’s eye and hear the comfort of my parents’ voices by my side filling me with the memories I hold dear once more and pass down to my children now.

I was birthed just as the violet crocuses in the meadow nudged their dainty goblet shaped heads through the thawing soil announcing with them spring. It was a chilly but clear morning when my mother woke early feeling the strain of an over ripe bladder. Retracing her steps towards the outhouse she counted her paces and filled her lungs with the crisp morning air. She was not due for several weeks but the pressure on her pelvis had increased inconveniencing her by doubling her trips to the bathroom. Upon her return to the farmhouse she lit a fire and began to prepare her morning meal of oat groats. She stoked the embers and rearranged logs when she felt a syrupy substance stream down her thigh. Standing in a puddle of her own making she contemplated whether or not she emptied her bladder in its entirety. Looking down, she saw blood mixed with her waters and simultaneously felt pain pulse through her abdomen stealing her breath. She lowered herself into a crouch and alternated between cradling her immense belly and holding her ankle bones for balance. The contractions were hard and fast keeping her low to the ground.

Da had finished the milking chores and quickened his pace back to the house to ease his wife’s burden with breakfast. He entered the kitchen with a fresh pail of the sudsy drink he craved and found his wife laboring on the wooden floor. Da jumped immediately into his rehearsed role of midwife, laying fresh towels down across the bed they shared and filling a basin with warm water. He hefted my mother from her crouch to a more comfortable position on her pallet, climbing in behind her massive naked body, massaging her cramping back and belly.

Maura had not birthed before and without the advice of a midwife she followed her instinct. My da having witnessed many animal births helped prepare my mother by massaging oils around her perineal tissue hoping she wouldn’t tear. When she felt the pressure was at its greatest and begged to push, Da rearranged himself in front of my mother’s belly in between her legs, and together with four loving hands entwined they brought me gently into the world.

“A girl!” Da exclaimed out of breath, worry etching itself across his brow in deep furrows.

The seconds ticked by and I had not yet mustered a cry. My airways were clogged with birthing matter and mucus and my skin was turning grey. Da resuscitated me by putting his largemouth across my small nose and mouth and sucking deeply. Suck-spit-repeat, he did this several times to no avail, when finally he held me upside-down and whacked my back. On cue I wailed, no longer safe in the warm confines of my mother’s womb.

The year was 1850 and I was blessed and named Tabitha Colleen Salt.

Tabitha

was my name alone but

Colleen

was a tribute to my paternal grandmother whose blessing and purse made it possible for us to be on American land farming our small plot of acreage in West Chester, New York.

Salt,

our sir name, was assumed and passed down by our great great grandfather who worked in the salt mine in Northern Ireland near Carrickfergus. The story goes that great great grandfather Salt lived to a ripe age of one hundred and seven; his longevity, he claimed, was due to the healing properties of the mineral.

Chapter 1 City Life 1860

My head was itchy, particularly on the base of my skull behind both ears, and my fingernails had dried blood under them from the scabs I scratched open sometime in the night. Mama was clawing at her skin too, not just on her head but also on her woman parts. One time I saw her woman parts when she climbed out from our wash basin and reached for a towel. I didn’t mean to look but I was curious and surprised to see a little puff full of hair there too. Now she was itching that place a lot.

The school teacher called it “lice.”

“Tabitha Salt,” Miss Marianne pulled me gently aside one day, “you may not be present in school until your head lice are gone, they are not only contagious but disrupting the other students when you itch so much. You can hardly sit still.” When I told my mama I was cast out from the classroom she cried softly into her open hands before pulling me in for a hug.

“Well, okay then, we will get rid of it at once and get you back into school,” she said with a conquering nod of her head and faraway gleam in her eyes. If there was one thing my mama was determined about it was my education. She and my da didn’t risk their lives on board the

Emma Prescott

in 1847 only to die from starvation or stupidity once on solid ground. Together they sailed from their beloved Galway towards religious freedom and a brighter future in America where they believed education was the key for a better life.

The lice came in on one of the shirts we laundered, which was not unusual given our clientele included

manky

sailors and dock hands. The critters attached to our hair and got into our bed sheets. The scavengers bit us something fierce feasting on our dry scaly skin before laying eggs. The nits were barely visible so you couldn’t snatch them up or swat at them like a fly. We had to cut our hair and wash with lye soap, and scald our clothes and sheets. Our mattresses were stuffed with straw, horsehair and old rags to even the lumps, but now they would have to be burned and we would sleep on the floor until we could buy or make new ones. The thought of fresh plumped straw mattresses was pleasing; my back was getting sore from these old ones. Plus they smelled rank, but my mama said we had to make do and that’s what we did.

We walked hand in hand to the barbershop on Bowery Street that offered shoe shines and dental work as well as haircuts and shaves, and asked how much to cut my hair. The barber was settling a customer into a reclining red leather chair, draping him with cloth and lathering his cheeks, chin and neck with white fluffy foam for a shave. Without looking up he said very curtly that he didn’t do girls hair and sent us to a salon house down the street.

“We’ll we certainly don’t need up do’s, do we? If the barber can’t help us we will tend to it ourselves.” We left the barber shop and when we got home my mama used her sewing scissors on my curls instead. The shear’s ends weren’t sharp so it hurt badly, I cried when I saw my red curly tendrils of hair drop to the floor. All my pretty curls were lying around my feet and soon after all my mama’s pretty curls were laying around my feet too. We sobbed and then laughed when we swooshed our heads back and forth; they felt so light and airy. But we had to cut them closer to the scalp where the eggs were laid. We went back to the barber and asked if he would shave us now and after he dipped his razor into some bluish liquid he did, for a nickel.

We each wore red handkerchiefs over our heads to cover our baldness, but I never thought my mama, Maura Salt, looked so pretty. Her blue eyes sparkled with flecks of gold and her freckled cheeks looked fuller, her right cheek looked rosier too.

She had a toothache she said, but when I looked at it from underneath I didn’t see a hole or black spot among the grooves that would indicate a cavity. She could only eat tepid foods because anything cold or hot caused discomfort; she chewed on her left side and after a few days became sluggish and bedridden. After several more days of the pain rendering my mama immobile, she gave in and sent for a dentist. She could have had the barber look at it, but she preferred someone with only one specialty. The dentist told her the tooth would need to be pulled immediately, and it would cost two dollars.

“Tabitha, open my top dresser drawer, behind the stockings that need mending you will find a pouch. Count out two dollars in change, then bring the coins to me please.” After I counted the money, I replaced the pouch and noted the light weight of it now, making me feel uneasy.

Two burly men accompanied the dentist filling up all the space in the undersized two room dwelling we rented from our land lady, Mrs. Canter. They offered my mama a three finger full shot of Jim Beam whiskey that she threw down her throat quickly so they could get on with it. They offered one to me too so I would sleep through the bellowing but I said, “No thank you, I am much too young for whiskey and I wish to help my mother.” So I held my mama’s clammy hands tight and the big man with the black suspenders and greying white shirt that desperately needed laundering held her shoulders back and down. The smaller mustached man sat across her legs. The dentist put a large metal tooth puller that resembled a key into her delicate mouth, counted to three and twisted the instrument clockwise before pulling with all his might at the tooth. The tooth cracked in several places, blood poured down my mama’s chin, and the dentist wiped at the sweat running into his eyes and said he would have to charge more to get all the splinters out. By the looks of his grimace, he didn’t like causing his patient pain any more than she liked receiving it. Tears flowed from her eyes and I kissed her hands and squeezed them tight to give her courage.

“It will be all right soon,” I said. Mama, frozen with fear, nodded at my encouragement and mustered the strength to withstand the increasing pangs in her mouth.

“Sir, maybe you ought to have a shot of that whiskey,” I said to him without cynicism.

He chuckled at me as if I were a comedian and wiped his sweaty brow again before looking deeper into his patient’s mouth.