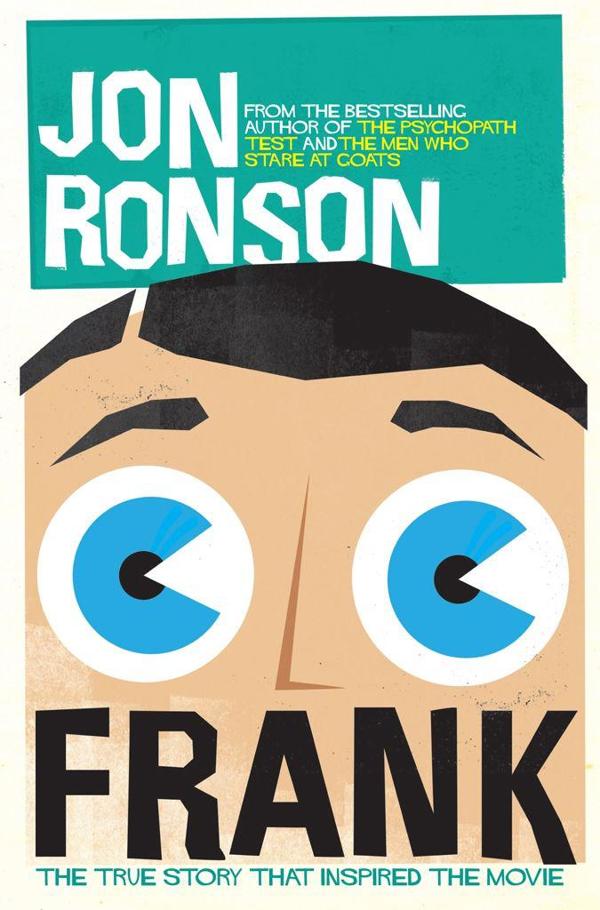

Frank: The True Story that Inspired the Movie

Read Frank: The True Story that Inspired the Movie Online

Authors: Jon Ronson

| Frank: The True Story that Inspired the Movie | |

| Jon Ronson | |

| (2014) | |

| Tags: | ttt |

FRANK

THE TRUE STORY THAT INSPIRED THE MOVIE

JON RONSON

PICADOR

To Stevie Lee

Frank

, the movie.

One day in 2005 I was in the park with my little boy when my phone rang.

‘Hello?’ I said.

‘

HELLO!

’ yelled Frank Sidebottom.

‘ . . . Frank?’ I said.

‘

OH YES

,’ said Frank Sidebottom.

We hadn’t spoken in fifteen years.

‘It’s been so long,’ I said.

Between 1987 and 1990 I was the keyboard player in the Frank Sidebottom Oh Blimey Big Band. Frank wore a big fake head with a cartoon face painted on it – two wide bug

eyes staring, red lips frozen into a permanent half-smile, very smooth hair. Nobody outside his inner circle knew his true identity. This became the subject of feverish speculation during his

zenith years. His voice, slightly muffled under the head, was disguised too – cartoonish and nasal, as if he was a man-child pretending to be a nightclub comic. Our act involved us doing

amateurish plinkety-plonk cover versions of pop classics such as ‘I Should Be So Lucky’ and ‘We Are The Champions’. Frank was all a little wrong, like a comedian you’d

invent in a dream – funny but not funny, meticulous and detailed but repetitive, innocent but nightmarish in a certain light. We rode relatively high. Then it all went wrong.

And now Frank was on the phone. He was ready to stage a comeback. Maybe I could help by writing an article about my time in the band? I said of course I would. When I got home from the park I

tried to remember our lives back then.

***

Frank Sidebottom.

In 1987 I was twenty and a student at the Polytechnic of Central London. I was living in a squat in a huge decrepit townhouse in Highbury, North London. The students who rented

proper rooms ended up miles away in places like Turnham Green, while the squatters lived for free in salubrious places like Islington and Bloomsbury. It was an otherworldly life. You could find

yourself squatting in some abandoned mansion with ballrooms and chandeliers. One group lived for a while in the Libyan Embassy in St James’s Square. A staff member had shot out of the window

at an anti-Gaddafi protest and a policewoman had been killed. The Embassy staff fled and the squatters moved in.

Most of the squatters were sweet-natured, but sometimes you’d find yourself living with chaotic people who were too frenzied for the mainstream world. In Highbury I’d stand in the

kitchen doorway and watch a man called Shep smash all the crockery every time Arsenal lost. He’d grab cereal dishes from the sink and hurl them in a rage across the room, his dreadlocked hair

tumbling into his face like he was some kind of disturbed Highland Games competitor or a Dothraki from

Game of Thrones

.

‘He is

SO

mentally ill!’ I’d think with excitement as I stood in the doorway. Arsenal were destined to lose 25 per cent of their games in the 1987/1988 season, finishing

sixth. Shep was a terrifying

Grandstand

football-score service. We were in for a tumultuous time in the communal kitchen.

One time Shep noticed me staring at him. ‘What?’ he yelled at me. I didn’t say anything. I felt like a cinema audience watching an adventure movie, emotionally engaged only in

the shallowest way. I was just delighted to not be living in Cardiff any more.

In Cardiff, where I had grown up, I’d been bullied every day: blindfolded and stripped and thrown into the playground, etc. It was the sort of childhood a journalist ought to have –

forced to the margins, identifying with the put-upon, mistrustful of the powerful and unwelcome by them anyway.

I dreamed about becoming a songwriter. My handicap was that I didn’t have any imagination. I could only write songs about things that were happening right in front of me.

Like ‘Drunk Tramps’, a song I wrote about some drunk tramps I saw being ignored by businessmen:

Drunk tramps

Ignored by businessmen

They walk right past you

Don’t even see you

But you’re the special ones!

With pain but hope in your eyes

Drunk tramps

I did make some money busking on my portable Casio keyboard. There was one song I played fantastically well. It was a twelve-bar blues in C. It was literally the only song I knew how to play.

For busking this was fine – nobody stayed around long enough to become aware of my limitations. But one day a man approached me and said he ran a wine bar in Guildford, south-west of London,

and did I want to play a set at his club?

‘That sounds great,’ I said.

I caught the train to Guildford and found the wine bar. I set up my keyboard and played my song. The owner turned to his bar staff and gave them a look to say, ‘See?’

After ten minutes I stopped. There was a lot of applause. Then I played my song again but slower. Then I played it again, but back at the original speed. Someone shouted, ‘Play a different

song.’

I looked at the crowd. They were evidently puzzled. And irritated. A fake pianist had entered their world and was banging away at the keys, a young man being odd and dysfunctional on the

makeshift stage, presumably unaware not just of what was required of a wine-bar pianist but of how to be an adult human in general. Panicked, I hurriedly invented something – an

unsatisfactory improvisation around my song. The owner asked me to stop and go home.

***

I went to comedy shows. I’d creep backstage and stand there, looking at the comedians. I saw Paul Merton and John Dowie try and out-funny each other in a gloomy

underground dressing room at a club in Edinburgh. Paul Merton made a joke. John Dowie responded with something funnier, then Paul Merton said something funnier still, and so on. Everyone was

laughing but it was tense and disturbing, like the Russian roulette scene from

The Deer Hunter

.

Backstage at a different club the comedian Mark Thomas stalked angrily over to me.

‘You always just

stand

there,’ he said. ‘When are you going to

do

something?’

So I decided to try. I put myself forward in the student union election to become the college entertainments officer.

It was to be a year’s sabbatical. I’d be in charge of two venues – a basement bar on Bolsover Street in Central London and a big dining hall around the corner

on New Cavendish Street. I’d have a budget to put on discos on Fridays and concerts on Saturdays and comedy on Tuesdays. Then after a year I’d return to finish my degree. Nobody stood

against me. It was a one-horse race. I was elected.

The entertainment office was on the top floor of the Student Union – a 1960s building in Bolsover Street. I’d sit in the corner, the social secretary elect learning the ropes from

his predecessor. I took it all in – how he negotiated fees, dealt with the roadies and the bar staff, even what he said when he answered the phone. He said, ‘Ents.’

He warned me that the big music-booking agents tended to see the likes of us as easy prey. If anyone would book their terrible bands it would be us. History would prove this right. I

did

book their terrible bands.

One day I was sitting in the office when the telephone rang. I was alone. My predecessor was off dealing with some issue. I wasn’t supposed to answer the phone. But it kept ringing.

Finally I picked it up.

‘Ents,’ I said.

There was a silence. ‘

What?

’ the voice said.

‘ . . . Ents?’ I said.

‘Oh,’ the man said. ‘I thought you said Ants. Jesus! OK. So Frank’s playing at your bar tonight and our keyboard player can’t make it and so we’re going to

have to cancel unless you know any keyboard players.’

I cleared my throat. ‘I play keyboards,’ I said.

‘Well you’re in!’ the man shouted.

I glanced at the receiver. ‘But I don’t know any of your songs,’ I said.

‘Wait a minute,’ the man said.

I heard muffled voices. He came back to the phone. ‘Can you play C, F and G?’ he said.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Well, you’re in!’ he said.

The man on the phone said I should meet them at the soundcheck at 5pm. He added that his name was Mike, and Frank’s real name was Chris. Then he hung up.

I looked at the receiver.

I arrived at the bar at exactly 5pm. The place was dingy even in daytime – we were deep in a basement – and empty except for a few men fiddling with equipment some

distance away across the sticky carpet near the stage.

‘Hello?’ I called.

The men turned. I scrutinized their faces. In the three hours since the phone call I’d learnt a little about Frank. Frank Sidebottom – how he wore a big fake head on stage and there

was much speculation about his real identity. Some thought he might be the alter ego of a celebrity, possibly Midge Ure, the lead singer of the band Ultravox, who had just had a huge hit with the

New Romantic song ‘Vienna’, and was known to be a big Frank Sidebottom fan. Which of these men looking at me might be Frank? And how would I know? If I looked closely would there be

some kind of facial indication?

I took a step closer. And then I became aware of another figure kneeling in the shadows, his back to me. He began to turn. I let out a gasp. Two huge eyes were staring intently at me, painted

onto a great, imposing fake head, lips slightly parted as if mildly surprised. Why was he wearing the fake head when there was nobody there to see it except for his own band? Did he wear it all the

time? Did he

never take it off

?

‘Hello, Chris,’ I said. ‘I’m Jon.’

Silence.

‘Hello . . . Chris?’ I said again.

He said nothing.

‘Hello . . . Frank?’ I tried.

‘

HELLO!

’ he yelled.

Another of the men came bounding over to me. ‘You’re Jon,’ he said. I recognized his voice from the telephone. ‘I’m Mike Doherty. Thank you for

standing in at such short notice.’

‘So,’ I said. ‘Maybe we could run through the songs? Or . . . ?’

Frank’s face stared at me.

‘Frank?’ Mike said.

‘

OH YES?

’

‘Can you teach Jon the songs?’ he said.

At this Frank raised his hands to his head and began to prise it off, turning slightly away from me, almost as an act of modesty, like he was shyly undressing. I thought I saw a flash of

something under there, some contraption attached to his face which he seemed to quickly remove, but I wasn’t sure that had happened at all. It was all so fast and discreetly done.

‘Hello, Jon,’ said the man underneath. He had a nice, ordinary face.

‘Hello . . . Chris?’ I said.

Chris gave me a sheepish smile, as if to say he was sorry that I had to endure all the weirdness of the past few minutes but it was out of his hands. He took me to a corner and patiently taught

me the songs. I picked them up pretty quickly. They were indeed comprised almost entirely of C, F and G. There were one or two other notes, but certainly not the full range. They were mostly cover

versions of Queen and Beatles hits.