Fraudsters and Charlatans (15 page)

Read Fraudsters and Charlatans Online

Authors: Linda Stratmann

Tags: #Fraudsters and charlatans: A Peek at Some of History’s Greatest Rogues

After his successful extraction of money from Bogle Kerrich and Co., de Pindray next went to a Florentine shopkeeper called Phillipson to take up some more money on the letter of credit. The letter was left with Phillipson, but that evening Phillipson returned the letter to de Pindray saying he had some doubts as to its genuineness. De Pindray was in a difficult position. The operation had only just begun and already suspicions had been aroused. After banking closed that afternoon (the bank's hours were 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.) MacCarthy, one of Bogle's partners, met Phillipson, who, while not able directly to prove his suspicions, left MacCarthy with a very uncomfortable impression. He decided to speak to Bogle about it, but search as he might, he could not find him. Eventually, between 4 and 5 p.m., he left a letter at Bogle's lodgings stating his suspicions and asking to see him; but Bogle did not respond. MacCarthy did not see Bogle until the following morning, when he simply said that the note had spoiled his appetite but that he was not inclined to discuss it further.

Who should then arrive at the bank but de Pindray, who explained that having heard about the doubts and as âit is a point which touches my honour',

11

he was returning the £200. Moved by his frank and open manner, his defiance of all suspicion and an exquisite sensitivity that had led him to return money he might have retained, the bank agreed to take back the £200 and wrote on the circular letter that the payment had been cancelled at the desire of the bearer. Not only had de Pindray established his reputation but the annotation on the letter gave it a further stamp of genuineness. Where Bogle had been on the evening of 21 April was never discovered, but he might have been with de Pindray persuading him to defuse suspicion by returning to the bank.

Meanwhile, the other conspirators were having better luck. On 22 April Frederick Pipe obtained £600 from Nigra and Son of Turin, on the 23rd £800 from Pasteur Girod and Co. of Milan, and on the 24th £800 from Louis Laurent at Parma. From there he and Graham took a steamer to Leghorn and arrived at the Villa Micali to report their progress to de Bourbel and hand over the money to him, retaining some as their share. On 28 April de Bourbel was in Florence, where he deposited 1,700 gold napoleons with the accommodating Freppa.

Since the fraud had not yet been detected it was considered safe to continue, and Pipe and Graham proceeded to Rome, where on 28 April they obtained another £200 from Monsieur Le Mesurier. So easy was this transaction that Pipe returned and asked for another £1,300. At this, Le Mesurier hesitated, recalling that he had never honoured a Glyn's letter before. Pipe pretended great indignation. He said he had been sent out by his father to purchase some pictures and that if he did not receive the £1,300 he would return the £200, and once back in England commence an action against Glyn's, claiming the expenses of his wasted trip and damages at being prevented from fulfilling his engagement. He must have been convincing. Le Mesurier gave the matter further thought, consulted the English consul, and paid up. Alexander Graham obtained only £150 in Aix-la-Chapelle before becoming too ill to continue.

De Pindray left Florence with his letter of credit soon after the scene at Bogle Kerrich and Co. and proceeded to Venice, where he obtained £347 from Landi and Roncadelli and £40 from the brothers Dubois. On 29 April he was in Trieste, where he received £1,612 6

s

from Mr Richard Routh. This gentleman found de Pindray's manners so pleasing that on that very night he invited him to share his box at the opera and later take supper at his house. So friendly and trusting were the two by then that de Pindray left Routh his carriage to dispose of, asking him to remit the proceeds to him in Greece or Egypt. From there de Pindray, who may never have had any intention of surrendering most of his gains to de Bourbel, decamped with the whole of the money. What became of the carriage was never reported, but, according to

The Times

, Routh was ruined.

Marie Desjardins, disarmingly accompanied by a little girl and travelling in a private carriage with a courier, was finding that the fraud was running smoothly in the cities of the Rhine. She received £500 from Messrs Oppenheim and Co. in Cologne, £500 from Messrs Deinhard and Jordan of Coblenz, a further £520 from Gogel Koch and Co. of Frankfurt, and £500 from Humann and Mappes Fils in Mayence. She then proceeded in elegant triumph to Paris.

Perry, accompanied by D'Arjuzon, had difficulties from the start. In Liège Perry asked for the sum of £550 from the bankers Nagelmackers and Co. but was refused because he did not have a proper passport. Obliged to go to Brussels to obtain one, on the following day he returned and was able to draw £100, of which D'Arjuzon took charge of £80. In Brussels they did better with a fresh letter of credit, obtaining £750 from Engler and Co., of which Perry got £250. In Ghent Perry presented the letter on which he had received £100 at Liège to de Meulemeester and Son, but that firm, not having a letter of advice from Glyn's, declined to make a payment.

On 23 April Perry went to Antwerp, where he asked a Monsieur Agié for £750 on the same letter he had presented to Engler and Co. Agié was suspicious. He could see, as it was noted on the letter, that Perry had obtained £750 only the previous day, and he was surprised that a man of Perry's appearance (presumably a reference to Perry not being dressed as a gentleman) should require so much money. Perry had revealed that he was soon returning to England, and the banker thought it strange that he should be drawing money abroad so shortly before his return, when he could obtain the sum in England without paying commission. Agié smelt fraud. He refused payment, stating that he did not have the necessary advice from Glyn's, and after Perry had departed he wrote to Engler, who contacted the police. Perry was so rattled by the experience that he burned the incriminating document. On 25 April he was on board the Ostend steamer bound for London accompanied by Angelina Pipe when they were both arrested and questioned by the Belgian police. Angelina, while admitting she knew de Bourbel, D'Arjuzon and his mistress, Perry and Alexander, denied all knowledge of the fraud, but Perry, perhaps hoping for clemency, made a full statement of his part in the affair and openly named the other conspirators, including Allan Bogle.

The game was up, and it was clear that de Bourbel had greatly overestimated the potential rewards, since the gang made in total only £10,700 (about £700,000 today), excluding the £2,000 de Pindray had absconded with. The news first broke in the Brussels newspapers and then in

Galignani's Messenger

in Paris, but it was to be some weeks before the case became an international sensation.

Since the events of 21 April, things had been going on as usual at Bogle Kerrich and Co.; however, matters were about to take a serious turn for Allan Bogle. On 9 May the bank received a letter from Messrs Oppenheim and Co. of Cologne warning that forged letters of credit from Glyn's were in circulation, and there were rumours that Graham and de Bourbel were involved. That same evening a packet of papers arrived at the bank from Mr Fox (later Lord Holland), the English

chargé d'affaires

at Florence. Fox had received a copy of Perry's deposition from the Belgian authorities, and sent copies both to the Tuscan government and to Mr Kerrich. Kerrich, who had thus far entertained no suspicions of his partner, was appalled. As soon as the bank closed for the day he looked for Bogle in all his usual haunts and eventually that evening found him at his lodgings, where he confronted him with the documents. âHe appeared greatly distressed,' Kerrich said later, âso much so that it was painful to witness.'

12

Still wanting to believe in his partner's innocence, Kerrich waited for Bogle to say that he was not involved in the conspiracy, but he did not, and neither did he confess; he could only moan that he was ruined. Kerrich stayed with him for some time, and possibly afraid that his partner and friend would do something desperate, decided it was best not to leave him alone. He took Bogle to his mother's house, and left him there, that unfortunate lady and her two daughters âin a most painful state of distress'.

13

Graham, who had returned to Florence to be with his family, departed in secret as soon as he realised he was under suspicion.

There were a number of courses open to Allan Bogle. He could have made a complete denial of the charges; he could have gone to the English ambassador and lodged a protest; or he could have consulted a solicitor. It is tempting to suppose that an innocent man would have done all three. Instead, he returned home, took to his bed and despite all entreaties to come out and make a formal denial, did neither. On the following day, Kerrich sought out MacCarthy and told him about Bogle's situation. The two men went to see Bogle at his lodgings on 11 May between 11 and 12 in the morning, and found him still in bed. When he saw his two partners he became agitated and declared that he would never enter the bank again. Kerrich implored him to reconsider, but Bogle would not be moved and told the men to take away his keys. Kerrich urged him to get out of bed and show himself at his âusual places of resort',

14

but Bogle could only whimper âI cannot. I have not the spirits.'

15

Reluctantly, at Bogle's request, MacCarthy prepared a notice of dissolution of the partnership, which was duly signed. During the next few days Bogle left his lodgings only once a day to travel to his mother's house in a closed carriage, to dine.

By 10 May de Bourbel realised he must make his escape, but his name was too well known and to travel under his own passport would invite arrest. He was staying in Empoli, near Florence, from where he wrote to Freppa, imploring him to obtain a passport in Freppa's name, or if he could not, to supply him with the means to erase his name from his own passport so that he could substitute another. In due course he obtained what he needed and departed for Spain.

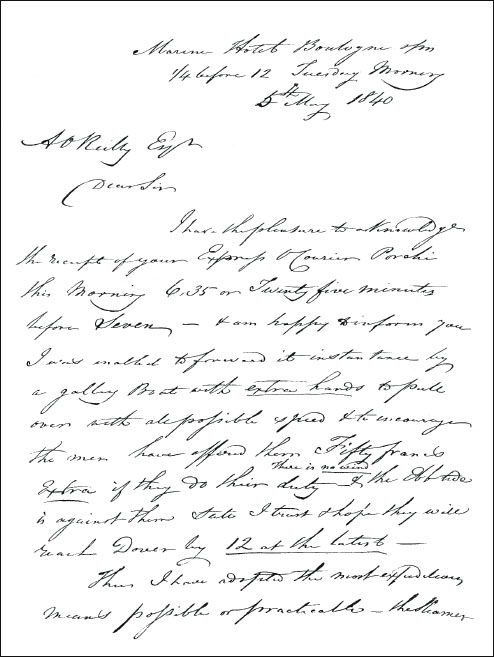

Letter of 5 May 1840 from M. Barry to Andrew O'Reilly about letters sent to

The Times

from the Continent. (The Times

International Archive

)

On 22 May Bogle unexpectedly arrived at the bank in great distress, saying he had been served with a signed order from the government of Tuscany to leave the Duchy in five days' time. He begged the partners to intercede on his behalf, and MacCarthy obligingly accompanied him to see Mr Fox, but all appeals were in vain. Bogle decided to go to England, despite anxiety about travelling through France, where he thought he might be arrested. Before he left, a packet, probably of letters, arrived at the bank from Algiers, addressed to Bogle, and Kerrich took it to him. Bogle retained the packet but did not open or refer to it. When he left Florence on 28 May he took it away with him.

On 23 May William Cunninghame-Graham, who had been living at Marseilles, returned to Leghorn on a steamer via Genoa, not suspecting that he was being closely watched by the Genoese banker who had been robbed of £1,500. On arrival Graham was denounced to the authorities, detained on board ship and questioned for three hours. He was carrying a great deal of money, and in his trunk were found four stamps for forging bills, including one for the firm of Glyn and Co.'s letters of credit. Despite these finds, it was felt that there was insufficient proof to identify him as one of the fraudsters, and the banker withdrew the charges. The stamps were returned to Graham before he was escorted over the Tuscan frontier and ordered never to return.

O'Reilly's article appeared in

The Times

on 26 May: it was explosive, naming all the members of the gang and quoting Perry's statement and de Bourbel's letters.

Graham's wife and daughters were ordered to leave Tuscany at the end of March, but before they did so they sent some of Graham's possessions, including his lathe, tools and machines, to the bank, asking that they be looked after. Kerrich had the items placed in a store-room, and for some months did not give the matter further thought.

On 8 June another packet from Algiers arrived at the bank, addressed to Bogle, and on 17 June a third. Mr Kerrich retained the papers but did not feel justified in opening them until 29 June, when Le Mesurier of Rome visited Florence. Under a growing conviction of Bogle's guilt, Kerrich showed the packets to Le Mesurier, who at once said: âThat paper is in the handwriting of the man who swindled me.'

16

The handwriting was later confirmed to be that of Frederick Pipe. The packets were opened in the presence of the English ambassador, and they contained letters, some of which were addressed to the Marquis de Bourbel and others to Charles Smith, poste restante, Florence, advising the recipients that the writer had arrived in Algiers and was planning to go from there to Marseilles and then Paris, and from there to London, and asking that his wife be advised to meet him at a pre-arranged place on 17 June. He further instructed that any letters should be sent to him under the name of Mr Lamont, General Post Office, London (Lamont was the maiden name of Mrs Pipe). It was thought that Charles Smith was in fact Bogle, although this could never be proven. This aside, the mere existence of the correspondence addressed to Bogle was highly incriminating.