From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (9 page)

Read From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 Online

Authors: George C. Herring

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #Geopolitics, #Oxford History of the United States, #Retail, #American History, #History

It was one thing to

plan

for governing and incorporating this territory, quite another to control it, and here the Confederation government was far less successful. Continued rapid settlement of the West and effective use of the land required protection from Indians and Europeans and

access to markets. The government could provide neither, encouraging among settlers in the western territories rampant disaffection and even secessionist sentiment.

The state and national governments first addressed the Indian "problem" with a massive land grab. Americans rationalized that since most of the Indians had sided with the British they had lost the war and therefore their claim to western lands. The state of New York took 5.5 million acres from the Oneida tribe, Pennsylvania a huge chunk from the Iroquois. Federal negotiators dispensed with the elaborate rituals that had marked earlier negotiations between presumably sovereign entities and instead treated the Indians as a conquered people. The British had not told the Indians of their territorial concessions to the Americans. The Iroquois came to negotiations at Fort Stanwix in October 1784 believing that the lands of the Six Nations belonged to them. Displaying copies of the 1783 treaty awarding the territory to the United States, federal negotiators informed them: "You are a subdued people. . . . We shall now, therefore declare to you the condition, on which alone you can be received into the peace and protection of the United States." In the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Iroquois surrendered claims to the Ohio country.

87

Federal agents negotiated similar treaties with the Cherokees in the South and acquired most Wyandot, Delaware, Ojibwa, and Ottawa claims to the Northwest.

Such heavy-handed tactics provoked Indian resistance. Native American leaders countered that, unlike the British, they had not been defeated in the war. Neither had they consented to the treaty. Britain had "no right Whatever to grant away to the United States of America, their Rights or properties."

88

Leaders such as the Mohawk Joseph Brant and the Creek Alexander McGillivray, both educated in white schools and familiar with white ways, found willing allies in Britain and Spain. Brant secured British backing to build a confederacy of northern Indians to resist American expansion. The Creeks had long considered themselves an independent nation. They were stunned that the British had given away their territory without consulting them. McGillivray tried to pull the Creeks together into a unified nation to defend their independence against the United States. In a 1784 treaty negotiated at Pensacola, he gained Spanish recognition of Creek independence and promises of guns and gunpowder. For

the next three years, Creek warriors drove back settlers on western lands in Georgia and Tennessee.

89

By the late 1780s, the United States faced a full-fledged Indian war across the western frontier.

The threat of war pushed Congress into making the pragmatic adjustment from pursuing a policy of confrontation to treating the Indians more equitably. Americans were also sensitive to their historical reputation. Certain that they were a chosen people creating a new form of government and setting higher standards of behavior among nations, they feared that if they did not treat Native Americans equitably, as Secretary of War Henry Knox put it, "the disinterested part of mankind and posterity will be apt to class the efforts of our Conduct and that of the Spanish in Mexico and Peru together."

90

American negotiators reverted to native ritual and custom in the negotiations, admitted that the British had no right to give away Indian lands, and even offered to compensate Indians for territory taken in earlier treaties. The Northwest Ordinance provided that Indians should be dealt with in the "utmost good faith" and that "their land and property shall never be taken from them without their consent."

91

Under Knox's direction, Confederation leaders also set out to Americanize the natives, conferring on them the blessings of "civilization" and eventually absorbing them into American society. The goal was the same; the methods changed to salve America's conscience and preserve its reputation. The new approach produced policies that would be followed far into the future. But it did not resolve the immediate problem of quelling Indian resistance.

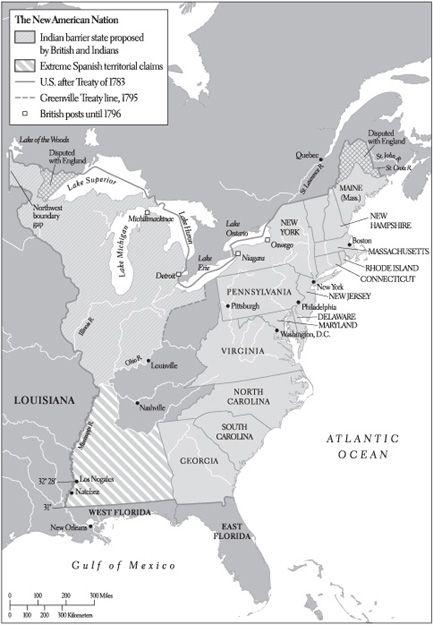

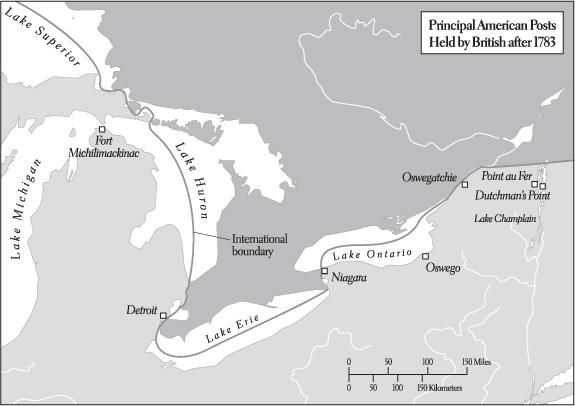

Equally serious threats came from the British and Spanish, and the Confederation's inability to deal effectively with these problems provided some of the most compelling arguments for a stronger national government. In the Northwest, the British refused to evacuate a string of frontier posts at Detroit, Niagara, and other points along the Great Lakes and used their presence on territory awarded the United States in the treaty to abet Indian resistance to American settlement of the Northwest. British diplomats insisted that they had not upheld their treaty obligations because the United States had not carried out provisions relating to payment of debts owed British creditors and compensation for Loyalist property confiscated during the war. In truth, Britain had refused to vacate the posts as a matter of policy, deliberately using the treaty provision that called for their departure "with all convenient speed" as a rationale to

reap maximum profits from the lucrative fur trade. Whenever Americans protested their retention of the posts, however, British officials hurled back at them charges of their own non-compliance.

The Confederation government could not get the British off its territory. Negotiations accomplished nothing; it could not force them to leave. Jay tried hard to meet British objections, but in the case of debts and treatment of Loyalists, the real power resided with the states. They were not inclined to fulfill, and in some cases actively obstructed, the vague promises made to creditors and Loyalists. The United States also sought French support. Nervous about U.S. obligations under the 1778 alliance, Jay at first explored the possibilities of extrication, only to be informed that "those who have once been the allies of France are her allies always."

92

Unable to wriggle free of the alliance, he sought to use it, appealing for French support in getting Britain to abide by its treaty obligations. France refused to meddle in Anglo-American affairs. In any event, French policy after the Revolution was "to have the United States remain in its present state" and not "acquire a force and power" that it "would probably be very easy to abuse."

93

Some French officials, including the

comte de Moustier, minister to the United States, were dreaming up an ambitious scheme to restore the French empire to North America.

The United States fared worse with Spain. Of all the European nations, Spain was the most threatened by the new nation and therefore the most hostile. A declining power, Spain was in poor condition to defend its once proud empires in North and South America. It was especially nervous about the Americans, whose restless energy and expansionist thrust endangered its weakly defended colonies in the Southwest. Spain sought to hem in the United States as tightly as possible by treaty or military force. It refused to recognize the Mississippi as the western boundary of the United States and contested the southern boundary set by the United States and Britain in 1783. It rejected American claims to free navigation of the Mississippi from its headwaters to the sea, a crippling blow to the economic viability of the expanding settlements in the Southwest. Spanish officials also negotiated treaties with and provided arms to Southwestern Indians to resist American settlement. They conspired with western settlers and rascals such as the notorious James Wilkinson to promote secession from the United States. After a visit in 1784, George Washington reported that "the western settlers stand as it were upon a pivot; the touch of a feather would turn them any way."

94

Jay and Spain's special envoy Don Diego de Gardoqui set out in 1785 to resolve these differences. Fearing that the rapid population growth in the American West might threaten its holdings, Spain sought a treaty as a shield against an expanding United States. It hoped to exploit northeastern distrust of the West to achieve its goal.

95

The government authorized Gardoqui to accept the boundary for East Florida specified in the 1783 Anglo-American treaty, but to reject 31° north for West Florida. He was to insist on Spain's "exclusive right" to navigate the Mississippi and seek a western boundary for the United States well east of that river and in some areas as far north as the Ohio River.

96

In return for acceptance of Spain's essential demands, he could offer a commercial treaty and an alliance guaranteeing the two nations' possessions in North America. A congressional committee informed Jay, on the other hand, that an acceptable treaty must include full access to the Mississippi and the borders set forth in the 1783 peace agreement. The secretary was given some flexibility on boundaries, but he could conclude no agreement without consulting Congress.

The Jay-Gardoqui talks took place in the United States, lasted for more than a year, and eventually produced the outlines of a deal. Gardoqui had first met Jay in Spain. Viewing him as self-centered, "resolved to make a fortune," and, most important, dominated by his socialite wife, the Spanish envoy concluded that "a little management" and a "few timely gifts" would win over Mrs. Jay and hence her husband. "Notwithstanding my age, I am acting the gallant," he cheerily advised Madrid, "and accompany Madame to the official entertainments and dances because she likes it."

97

In the best traditions of European diplomacy, he also presented Jay the gift of a handsome Spanish horse, which the secretary accepted only with Congress's approval.

Such extracurricular exertions could not overcome the standoff on the Mississippi. As Spain had hoped, Jay eventually concluded that Gardoqui would not give way on that issue and decided on an "expedient" that waived U.S. access to the river for twenty-five years. In return, Spain would grant the United States a generous commercial treaty, and the two nations would guarantee each other's North American territories. Jay did not discuss the terms with Congress, as he had been instructed—yet another manifestation of his independent cast of mind—although he did consult with individual legislators. A negative response from Virginian Monroe, who had drafted his original instructions, failed to deter him. In May 1786, he offered the agreement to Congress.

Jay's proposal exposed sharp sectional differences and sparked open talk of secession. The onetime Hispanophobe insisted that since Spain was the only European power willing to negotiate, the United States should conclude an agreement. He defended the terms on the basis of the commercial benefits: full reciprocity; the establishment of consulates; Spain's commitment to buy specified American products with much-needed hard currency; full access to the ports of metropolitan Spain. "We gain much, and sacrifice or give up nothing," he claimed. Concession on the Mississippi was "not

at present

important," he added, and "a forbearance to use it while we do not want it, is no great sacrifice."

98

Regarding a concession on the Florida boundary, he argued that it was better to "yield a few acres than to part in ill-humour."

99

Southerners thought otherwise. They minimized the value of Spain's commercial concessions and maximized the importance of the Mississippi. "The use of the Mississippi is given by nature to our western country,"

Virginia's James Madison proclaimed, "and no power on earth can take it from them."

100

Failure to gain access to the river would splinter the West from the East. Lurking behind heated southern opposition was the hope that the addition of new states beneath the Ohio River would enlarge their power in the national government. Jay's proposal required them to abandon their expansionist aims for the benefit of northern commerce. Monroe accused him of a "long train of intrigue" to secure congressional approval.

101

Westerners vowed to raise an army of ten thousand men, attack Spanish possessions, and even separate from the United States.

102

To "make us vassals to the merciless Spaniards is a grievance not to be borne," one spokesman thundered.

103

Northern delegates tried to mollify their southern brethren by holding out for the 31st parallel as a Florida boundary. But when seven northern states voted to revise Jay's instructions, southerners questioned the viability of the national government. "If seven states can carry a treaty . . . , it follows, of course, that a Confederate compact is no more than a rope of sand, and if a more efficient Government is not obtained a dissolution of the Union must take place."

104

It took nine states to ratify, and Jay reluctantly concluded that a "treaty disagreeable to one-half the nation had better not be made for it would be violated." Gardoqui went home empty-handed. The debate over the abortive treaty produced the sharpest sectional divisions yet. Southerners began to suspect that the deadlock threatened the unity of the new nation.

105