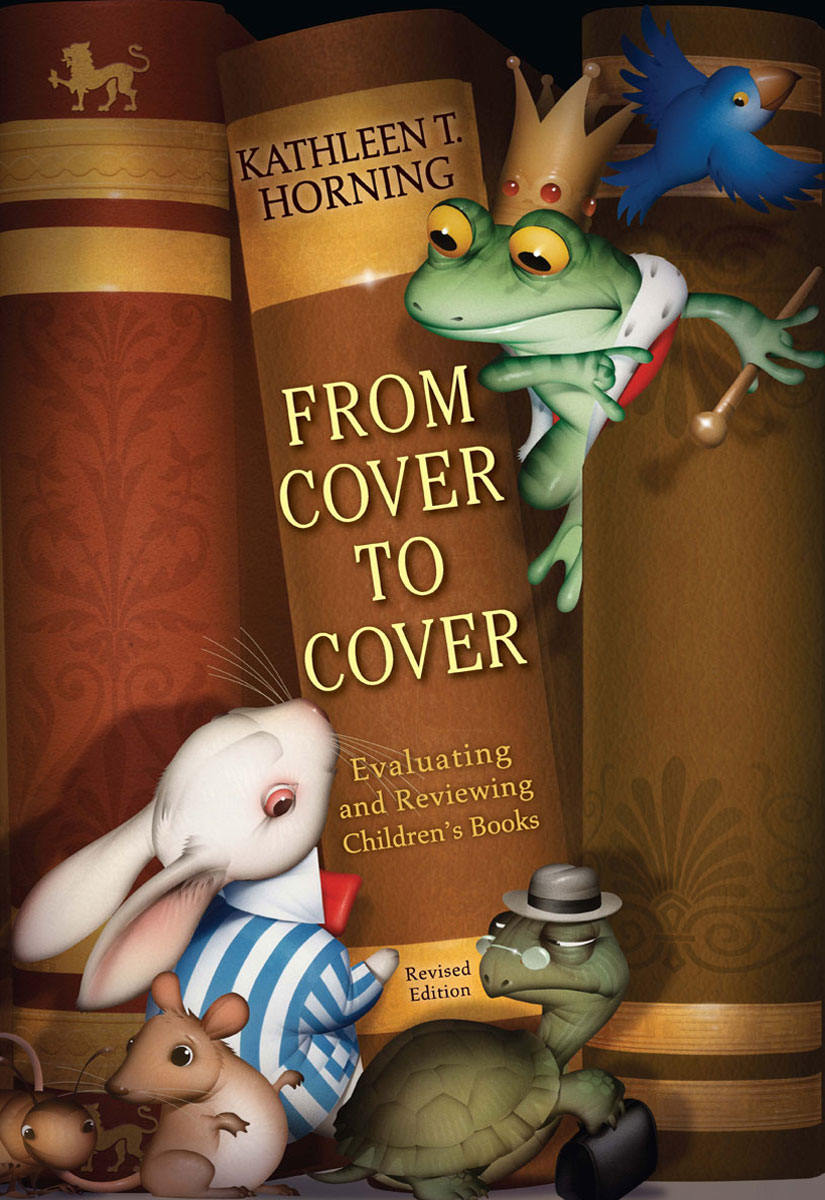

From Cover to Cover

Read From Cover to Cover Online

Authors: Kathleen T. Horning

From Cover to Cover

Evaluating and Reviewing Children’s Books

Revised Edition

For Emily

1.

A Critical Approach to Children’s Books

2.

Books of Information

3.

Traditional Literature

4.

Poetry, Verse, Rhymes, and Songs

5.

Picture Books

6.

Easy Readers and Transitional Books

7.

Fiction

8.

Writing a Review

With approximately five thousand new books for children being published every year, it may seem an overwhelming task to wade through them. But with this embarrassment of riches, it is important for adults who work with children and books to sharpen their critical skills so they can select the best books available. But how do we determine which books are the best ones? What makes a good children’s book? Are there simple standards we can apply across the board? Or are there different sets of standards for different types of books? Or for different needs or audiences? This book is meant to serve as a beginning place for those who want to evaluate or review books published specifically for children. It will provide concrete examples of aspects to consider when looking at children’s books with a critical eye.

DISTINCTIONS BETWEEN EVALUATION AND REVIEW

For our purposes, we will use the term

evaluation

to refer to a critical assessment of a book—in other words, the thought process one goes through in order to formulate an opinion of the book. Sometimes book

evaluation can be done very quickly, drawing on a wealth of professional or personal experience; other times it requires a great deal of deliberation, careful thinking, perhaps even consultation with outside sources of information. This book will offer guidelines for evaluating the various genres of children’s books: nonfiction, folklore, poetry, picture books, beginning readers and easy chapter books, and fiction. It will also offer advice on how to write a review.

A

review

is a formal written expression of the critical assessment, generally printed soon after the book under consideration has been published. Good reviews help readers create a mental picture of the book by briefly describing it and presenting an assessment of its quality.

WHAT MAKES A GOOD CHILDREN’S BOOK?

There are no quick, easy answers to this question because there are so many different kinds of children’s books that can be outstanding for different reasons. Furthermore, as times change and our perception of children evolves, so too do our standards for excellence in children’s books. Each chapter in this book will open with a brief history that will help provide a context for the type of books under discussion, followed by evaluative criteria, using examples from outstanding books. Newcomers to the field may wish to seek out these exemplary books to expand their general knowledge of children’s literature by reading some of the best books we offer children.

It’s been more than ten years since the first edition of

From Cover to Cover

was published, and in that time there have been changes in the

children’s book world. The chapters included here have been updated to reflect that, and the chapter on fiction now includes a section on subgenres. In each chapter new books have been included as examples of some of the best that children’s literature has to offer.

A Critical Approach to Children’s Books

Reading a book for the purposes of evaluation and review requires more attention to detail than reading a book for pleasure or for information. When you read to evaluate, your assessment of the book will ultimately affect other potential readers. It may make a difference as to whether or not a book is purchased for a library or a school or as a birthday gift for a child you’ll never meet. In fact, it may make a difference as to whether or not the book is read by a child at all. It is your professional responsibility to try to take your evaluation beyond a personal response.

This is not to say that your personal response doesn’t matter. It would be impossible for you to put it completely aside—you are a reviewer, after all, not a robot. What the responsible reviewer strives for is an informed and reasoned opinion, clearly articulated so that others can learn about books they haven’t read.

In essence, a children’s book reviewer reads and writes with two audiences in mind: (1) adults who read reviews to help them select books for children and (2) the children themselves. If a review is printed in a publication that has a national distribution, it may also be read by the author and publisher of the book in question; however, neither is the intended audience for your review. In other words, it is not your goal to write a

review to stroke an author’s ego or to pick a bone with a publisher.

Still, it is important to remember that most books for children are created with the best intentions in mind. No one sets out to produce a crummy book that kids will hate. If this is your initial assessment of a book you’re reviewing, it would be unfair and unwise to let it stand as your final one without a great deal of further consideration. You’ll need to take a closer look at the book. What was the author’s intent in writing the book? What qualities did the editor see that led him or her to believe that the book merited publication? Why did the illustrator choose this particular style? The answers to all these questions have their origins in the history of the book’s creation. While it isn’t necessary for you to know the details of a book’s publishing history in order to review it, an understanding of the general context in which children’s books are created will help you read more critically.

HOW CHILDREN’S BOOKS ARE PUBLISHED

Many publishing houses have divisions or departments that are devoted to publishing books for young people. These were, for the most part, established in the 1920s and developed through the pioneering efforts of women such as Louise Seaman Bechtel, May Massee, Helen Dean Fish, Marian Fiery, and Virginia Kirkus, who were the first children’s book editors. Unlike adult book divisions, which are driven by the consumer market (bookstore sales), children’s book divisions developed largely in response to an institutional market. Sales to libraries and schools accounted for a high percentage of the total number of children’s books sold. As library budgets began to shrink in the 1970s and 1980s, children’s book publishers began to turn their attention toward consumer sales as well, although the institutional market continues to be an important influence in the children’s book industry.

There are books that are created specifically for one market or the

other. Those that are produced for the institutional school market alone are called

textbooks.

They are generally sold to entire school districts rather than to individuals. They are also created in a separate division of the publishing industry that specializes in producing books to fit the exact needs of teachers working with specific school curricula and guidelines at various grade levels. Books that are produced with only the consumer market in mind are called

mass-market books

. These are generally produced as paperbacks or as picture books with inexpensive cardboard covers (such as Little Golden Books) and they may be sold in supermarkets, airports, drugstores, and convenience stores as well as in bookstores. While there are publishers that specialize in producing mass-market books, most children’s book departments produce mass-market books to some degree.

Books created for both the consumer market and the institutional market are called

trade books

. These are sold to schools and libraries, and they are also sold directly to consumers through bookstores. Both quality and child appeal are taken into account when weighing the sales potential. From the publisher’s point of view, the best kind of children’s trade book is one that will succeed in both the consumer and the institutional market and will continue to sell well for decades. This is the type of success guaranteed by a book that wins the Newbery or Caldecott Medal.

Most children’s books start out as an idea in the mind of an author. That may seem obvious to you, but I mention it here because many people seem to have the notion that ideas start with publishers, who then assign them to authors. People often ask children’s editors: “Why don’t you publish more books about X?” in a tone that suggests they hold editors personally responsible for the lack of X books. But editors don’t tell authors what to write. They must wait for X to develop in the mind of the author, and then they have to determine if it’s good enough

to publish. The editor’s role is to find and nurture the talents of authors and artists who will create good children’s books. If they cast their nets widely enough, their catch may include an author who will come up with the idea of writing about X on his or her own.

Once a manuscript is accepted for publication, the editor works with the author to help shape the book into its final form. An editor may make suggestions about chapters that need to be rewritten, characters that need to be developed, or ideas that need to be clarified. The ultimate responsibility for the writing, however, rests with the author. If the author has submitted the text for a picture book, the editor will choose an artist to illustrate it. While the author may see preliminary sketches of the illustrations, chances are that the author and illustrator will never meet while the book is in production. Generally the author has very little to say about the illustrations other than their factual content.

When the final version of the manuscript is completed, the editor—in conjunction with the designers—will estimate the number of pages there will be in the printed book, specify the

trim

(size of page), and decide the type of binding. He or she will also discuss jacket art with the art director, who will in turn assign the work to an artist if it’s not an illustrated book; most picture book jackets are illustrated by the artist doing the interior art. Again, the author generally has little or no say in such matters. The manuscript is turned over to a

copy editor

, who will read it to correct spelling, grammar, and inconsistencies in style and internal plot. A copy editor may question noticeable errors in fact but will not retrace every step of an author’s background research. In most cases the author has final say about the copy editor’s changes.

A copy of the manuscript is also given to a

designer,

who will choose an appropriate

typeface

. Based on the number of

characters

(letters, numbers, spaces, and punctuation marks) in the final manuscript, the designer will choose a typeface that will fill the number of pages estimated earlier.

The designer may print out sample pages at this point so that the editor can look at the

page layout

(what the printed page in the book will look like) and decide if the type and page design are appropriate for the look of the book. The size of type in a children’s book is especially important, as it often dictates the age level of the book’s audience. Children are surprisingly sensitive to typeface. If they decide it’s too small, they’re likely to reject a book as “too hard,” no matter the content. If they decide it’s too large, they may scoff at a book as “babyish.”

When the editor and designer have made the final decisions about typeface, number of lines per page, margins, and other design elements, the manuscript is set into pages. Computer-generated page proofs are circulated for proofreading and final corrections. An author rarely makes any substantive changes in the text at this point, although the author, editor, designer, and a proofreader will look at the proofs carefully in case there are any printer’s errors or any blatant mistakes that were somehow missed earlier. Meanwhile, the sales department estimates the number of copies in the initial print run. The production department will arrange to have paper—chosen for its color, weight, and cost—and material for the binding, often chosen to coordinate with the jacket, sent to the printer. The final approved pages are sent to the printer for the actual edition run.

Because of the visual nature of picture books, they undergo a different production process. After an artist has been commissioned to illustrate a picture book, he or she discusses layout and design with the editor and the art director and makes preliminary decisions about how each page will look. Next he or she prepares and submits

roughs

, detailed pencil sketches for each page spread. Usually, the designer creates paged layouts placing text with relation to the artist’s roughs and the trim size of the book. There can be several layouts or dummy stages before the roughs are approved, and the artist completes and delivers the finished artwork

for the book. The designer prepares a camera-ready digital

mechanical

that shows the position of text and illustrations and includes instructions for the printer. The first set of color proofs comes back from the printer, and they are carefully checked against the originals by the artist, art director, designer, and editor so that any problems with color, size, and position of the illustrations can be corrected. When these final decisions and adjustments are made, and after a few more proof stages for final checking, the book goes off to be printed and bound.

In the meantime, the editor has enthusiastically described the book to the company’s in-house sales representatives at the seasonal sales conference and has provided a description of the book for them to use in their catalog. They in turn will try to get the book into bookstores across the country. The publisher’s marketing and publicity departments have been working on behalf of the book, as well, to get the word out to the world that the book exists. A glowing description of the book will be placed into their print and/or online seasonal catalog. They may include the title in announcement ads of the season’s forthcoming books that appear in trade journals such as

Publishers Weekly

and

School Library Journal

. They may choose to buy advertising space in a children’s literature review journal that will specifically highlight the book. Or they may create posters, bookmarks, flyers, or buttons advertising the book to give away to librarians and teachers at professional conferences. They may promote the book through their company website, online catalogs, and blogs.

They will also send out

advance review copies

of the book (often specially printed from uncorrected proofs so reviewers can evaluate the book early) to professional journals and to some general publications. In addition, review copies are sent to large library systems and departments of education for their own internal review. Favorable reviews and recommendations for purchase by these large systems can be important

to the success of any children’s book, since institutional sales still account for a significant part of the children’s trade book market. Throughout most of the twentieth century, children’s librarians set the critical standards for children’s trade books, and they continue to have a great deal of influence in the twenty-first century. The ultimate prizes for a children’s author and illustrator are the Newbery and Caldecott Medals, respectively. These are the only book awards that have nationwide impact on sales, and they are given annually by children’s librarians under the auspices of the American Library Association.

Just as a bit of background about the publishing industry can help to inform your reading, so too can an understanding of the book itself as an object.

For the most part, children’s books are still considered as physical entities, although we are at a point in history where technology is rapidly changing. After a few decades of fits and starts,

electronic books

, or

e-books

, have finally become accepted in the adult trade publishing world, but they have been slower to take hold in children’s book publishing. While some experts have observed that children, with their affinity for computers and technology, would seem to be a natural audience for e-books, others have pointed out the special challenges the industry faces when it comes to children, from creating a satisfying electronic picture book to issues of access since many children do not own the necessary technical devices needed to read an e-book.

Although books may vary widely, there are several constants in the way they are designed that should be familiar to you. It’s useful to know the special vocabulary of the book—to know what endpapers are, for example, or what is meant when someone refers to flap copy. As a critical reader, you should be aware of all the parts of a book that contribute

to the whole. You may even find a piece of information in the author’s acknowledgments or on the copyright page that will help you with an assessment of the book.

Beyond the body of the book proper, created by an author and/or illustrator, we can look at three additional parts:

binding, front matter

, and

back matter

.

BINDING

The cover

: Children are notorious for judging books by their covers and that, of course, is the opposite of what the critic strives for. Most hardcover children’s trade books come with a paper jacket, or

dust jacket,

that includes color artwork designed to entice potential readers. The part of the jacket that folds around the inside of the cover is called a

flap,

and it contains printed information, known as

flap copy

. The front flap generally gives a brief summary of the book and typically concludes with a lot of superlatives about how great the book is, while the back flap often includes biographical information (

bio

) about the book’s creator(s).