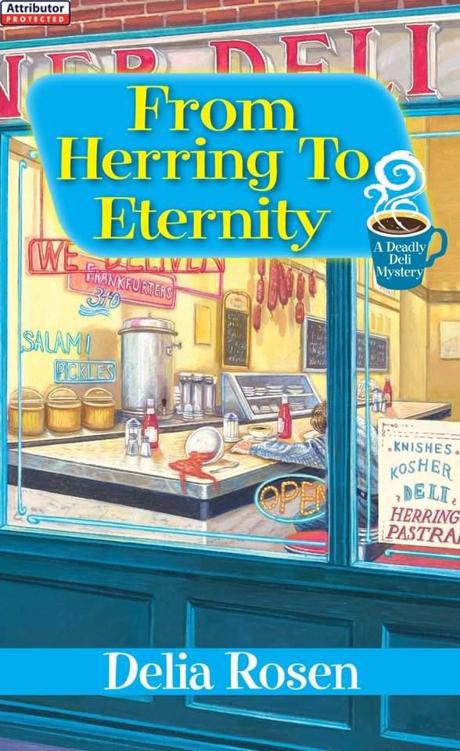

From Herring to Eternity

Also by Delia Rosen

A BRISKET A CASKET

ONE FOOT IN THE GRAVY

A KILLER IN THE RYE

From Herring To Eternity

Delia Rosen

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Also by Delia Rosen

Title Page

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Copyright Page

Chapter 1

A.J. strode into the deli kitchen, stopped, shuddered from her shoulders to her fingertips, then folded her arms and looked me square in my baby browns.

“I am

not

going back out there!”

I had been standing behind the long stainless steel table, scrambling eggs for Luke, who was filling in for my cook, Newt, when she entered. A.J. was the star of my waitstaff, the Pavlova of the serving tray. With just Raylene and Thom on the front lines during the breakfast rush, I couldn’t afford to lose her.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

Her thin, lightly freckled face was taut with horror as she said, “That witch is here.”

The ponytailed blonde was the poster child for southern gentility. When she used the term “witch” or anything that rhymed with it, I knew she meant it literally.

“Mad’s here for breakfast?” I asked.

A.J. nodded.

That’s odd

, I thought. “Don’t worry—I’ll take care of it, A.J.”

“Sorry, but her face—”

“I know.”

“It even scares Thomasina.”

“I understand. See to the other customers,” I said as I finished scrambling the half-dozen eggs and handed the bowl to Luke.

Managing a restaurant is 10 percent stirring, 10 percent cutting, and 80 percent psychoanalysis and handholding.

“Breakfast, huh?” Luke said as he flipped extra-crispy slices of turkey bacon. “Should I stir-fry frog’s eyes in hen’s blood for the Chicken Wiccan Omelet?”

“Only if you plan to eat it,” I told him.

“You’re disgusting,” A.J. said to him as she turned and went back into the dining room.

“Hey, Ozzy used to gnaw off bat heads!” the aspiring rocker shouted after her.

“I’m not sure the folks at the counter are interested,” I said as I removed my apron and laid it on the table.

“Well, they should be,” he said. “It’s history, man.

History

.”

“Right. Cook, Luke, unless

you

want to be history.”

“Haw!” he laughed.

He was right. God help my loyalty to Uncle Murray’s staff. They had seen me through some tough days and a supersteep learning curve when I’d inherited Murray’s Deli from my late uncle. I owed them all. And however challenging they could be, I liked them.

It was difficult to believe it had been three hundred sixty four days since I first came down here to run the place—I, Gwen Katz, an NYU-educated accountant, a New Yorker whose idea of making lunch was a snap-shut plastic container, tongs, and a salad bar. I had only been to Nashville a couple of times during the previous twenty years to visit my I-left-your-mother-to-figure-my-life-out father and his brother, and friends had urged me to sell the place. But I had just gotten out of a bum marriage, was tired of working at a brokerage firm that was under fire from Obama and from frightened investors—talk about DP, “Double Peril”—and at thirtysomething I decided to do something different.

I’d succeeded. Folks around here now referred to me as “Nash,” short for “Nashville Katz,” as though I was southern-born and raised on the pastrami game. In addition to learning the deli business—with the help and endless good will of my God-fearing hostess, Thomasina Jackson, who knew more about the place than I did—I’d also managed to be onhand for a couple of homicides. I hadn’t reached the point of wondering whether I was some kind of human GPS signal for the Grim Reaper, but it was a little freaky.

Speaking of freaky, that was the word which best described the lady who was sitting alone by the side window at the end of the counter. Her name was Mad Ozenne, the “Mad” being short for Madge. According to Thom, she was Creole on her father’s side, Missourian Ozark on her mother’s side, and living in Nashville because she had planned to marry a Cherokee jeweler named Jim Pinegoose. But the artisan had died just days before the wedding, suffering heart failure during a tribal competition dance at the Twentieth Annual Tennessee State Pow Wow in 2003.

“And just last week she tried to contact him through the tribal

atskili

,” Thom had told me. “A witch. It was the talk of the church. Parishioners said they saw her and Sally Biglake in the woods behind Barbara Mandrell’s home, incantationing.”

“Why there?” I had asked.

“No one knows,” Thom had said, inadvertently spookily.

“Maybe she likes the song ‘Stand by Your Man,’” I’d suggested helpfully.

Now, here’s what I meant about the attentive patience of my staff. Thom had looked at me sadly, took my hand in both of hers, and said, “Girl, that was Tammy Wynette. You want to take care not to make mistakes like that among the customers, ’less you want them laughing behind your Yankee back.”

“Good advice,” I had said. “And how should I take the—what did you call it? Incantationing?”

“Seriously,” Thom had replied without a trace of sarcasm. “That stuff has some potent qualities.”

The woodsy witchery was forgotten for more important business. The next day, Thom had given me a big stack of CDs. Within weeks, I was so immersed in country that I not only knew the lyrics to “Jambalaya,” I knew what “Me gotta go pole the piroque” meant.

No longer a mistrusted Northerner, I beelined smiling through the “good mornings” of the diners to station number seven.

Mad Ozenne was in her early fifties, a tiny, bony woman whose long graying hair hung loose over her ears. She wore cotton crinkle skirts and caftans, typically with astrological patterns or crescent moons. The pagan attire wasn’t the strangest thing about her, however. What had set A.J. off, and what drew stares from diners who did not know Mad, were the tattoos on her cheeks. She had all thirty-two teeth inked on the outside.

Sweet young Dani, who usually worked the afternoon shift—and was no stranger to piercings and body art—once asked, “Ma’am, forgive my askin’, but didn’t that

hurt

?”

“Very much,” the woman had replied.

“Then why—?”

Mad had looked up at her and said, “The better to eat you with, my dear.”

When she came for lunch, Mad always ordered chicken broth soup with a side of

gefilte

fish, heavy on the horseradish. I was frankly curious why she was here for breakfast and what she’d have. The woman was studying the menu, mouthing the words as though they were a runic conjuration.

“Good morning,” I said pleasantly. “We don’t usually see you here so early.”

“I’m not an early riser,” Mad agreed. “The dawn moon and Venus required it. The earth is not happy. I will have three raw eggs in a bowl with Hebrew salt on the side, and four slices of dry rye toast.”

“You mean kosher salt,” I clarified.

“The large crystals.”

“Yes, that’s kosher salt,” I said. “You got it.”

“It’s very tasty,” Mad said, opening and closing her mouth in anticipation and causing her ink teeth to move in an unnatural, sinuous fashion.

“I’ll be right back,” I smiled.

I was accustomed to patrons making innocent comments about “Hebrew” this and “Jew” that. I liked to believe it was uneducated shorthand, not malice. For nearly a year, though, I wished that some of these people were thrust suddenly and without preparation into Manhattan and faced the quick education I had had to endure down here. They wouldn’t survive a week.

Mad watched me as I hurried off. As I passed the end of the counter on the way to the kitchen, Lippy Montgomery stopped humming—it was more like one of those soft, sibilant whistles where your tongue is pressed to the inside of your upper teeth. He swiveled and tugged at my sleeve. His round face, looking older than its late-twentysomething years, with its chronic hangdog expression, seemed more distressed than usual. He held the check in one hand; the other hand rested protectively on the battered trumpet case which sat on his lap, plump and frayed like a pet Pomeranian.

“Excuse me, Nash, but I don’t think this check is right,” the young man said.

“What’s wrong?” I stepped around to glance at the bill.

“The herring platter, while uncommonly tasty, as was the grapefruit juice, is usually six ninety-five, not seven-fifty.”

“The Russians are charging us more,” I explained. “We’re not making an extra red cent profit—if you’ll pardon the pun.”