Gabriel's Journey (13 page)

Authors: Alison Hart

Pa stays very quiet so I can't tell what he's thinking.

“When this war's over,” I rush on in my excitement, “the North and South will both need horses. After you're mustered out of the army, we'll buy our own farmâMa, you, me, and Annabelle if she wants. A farm with sweet grass and a few mares so Aristo can sire a whole herd of fine Thoroughbreds! Maybe we'll even head out west, where land is cheap.”

When I pause to take a breath, I swear I can see those horses in the firelight: strong steeds galloping free, their manes blowing, their nostrils flaring as they race across the pasture of flickering flames. This journey has been long and hard and full of death, but somehow it hasn't brought me to an end. It's led meâled

all

of usâto a beginning.

“Do you see them, Pa?” I whisper. “

Our

horses on

our

farm? Or am I dreamin'?”

“You ain't dreamin'.” Pa's arm tightens around my shoulder as he gazes into the fire, a smile slowly creasing his face. “I see them, Gabriel. I see those horses, too.”

Gabriel and his family and Captain Waite are fictional characters, but the story of the Fifth United States Colored Cavalry and the battle of Saltville and the Saltville Massacre is real. The following characters in the story are based on real soldiers who fought at the battle.

NION

:

General Stephen G. Burbridge:

Relieved of command several months after the defeat at Saltville.

Colonel Charles Hanson:

Wounded in action; Confederate surgeons saved him from being murdered by Rebel guerrillas.

General Hobson:

Commanded a brigade of Kentucky mounted infantry and cavalry at the battle of Saltville.

Colonel Robert Ratliff:

Originally commander of the 12th Ohio; also placed in command of the 11th Michigan and the Fifth Colored Cavalry for the battle of Saltville.

Colonel James Brisbin:

Wrote a letter after the battle proclaiming the courage of the soldiers of the Fifth.

Colonel James F. Wade:

Promoted based on his performance at the battle of Saltville.

Private Joseph Black:

Listed as missing in action after the battle of Saltville.

Private George Lewis:

Wounded in the left side during the battle of Saltville. Listed as murdered by the enemy.

Private Andrew Crutcher:

Missing in action after the battle of Saltville; later identified as killed in action.

Corporal George Vaughn:

Promoted to quarter sergeant after the battle of Saltville.

ONFEDERATE

:

Champ Ferguson:

Rebel guerrilla; one of several men who were believed to have murdered wounded soldiers of the Fifth. Hanged (for other war crimes) on October 20, 1865.

General John C. Breckenridge:

Arrived in Saltville with a force of cavalry after the Union army departed.

G

ABRIEL'S

J

OURNEY

B

LACK

S

OLDIERS IN THE

C

IVIL

W

AR

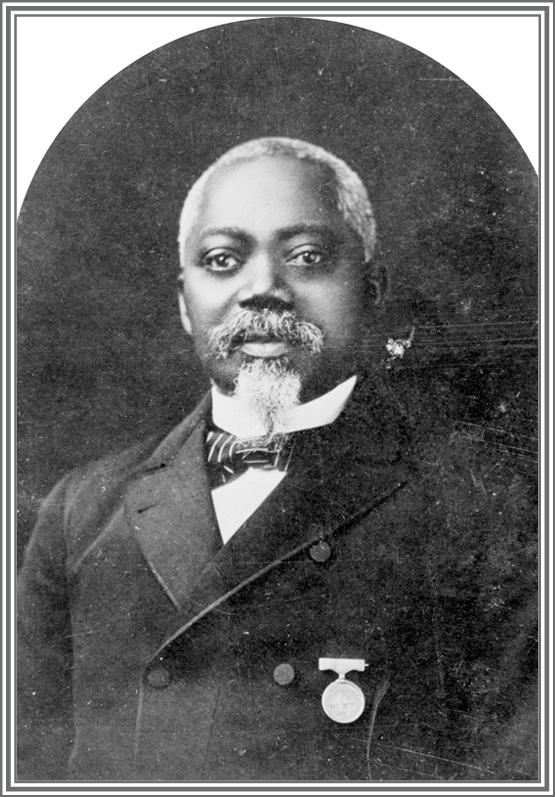

B

y the end of the Civil War, 178,975 soldiers had served in the United States Army as members of the U.S. Colored Troops. Another 9,695 African American men served in the U.S. Navy. There were 135 infantry regiments, 7 cavalry regiments, 12 regiments of heavy artillery and 10 batteries of light artillery. Black soldiers fought in thirty-nine major battles. Some of them served as officers, surgeons, and chaplains. More than a dozen black soldiers received the Medal of Honor after the war. Sergeant William H. Carney was the first African American to be awarded this medal. He was honored for carrying the Union flag to safety despite being shot in the head, arm, leg and chest.

It was not easy for most blacks to become soldiers. Thousands of slaves risked punishment and death when they ran away to enlist. Some were shot by Confederate soldiers. Others were hunted and caught by their angry masters. Kentucky slave Elijah Marrs wrote: “. . . we were in the recruiting office in the city of Lexington. . . . By twelve o'clock the owner of every man of us was in the city hunting his slaves . . .”

When the Civil War began in April 1861, many African Americans wanted to join the fight. But the U.S. War Department did not allow blacks to enlist. Even though many white Northerners were against slavery, they did not feel that blacks were skilled or brave enough to become soldiers. Others worried about giving weapons to blacks. And most Northerners believed that the war was being fought to restore the Union, not to free the slaves.

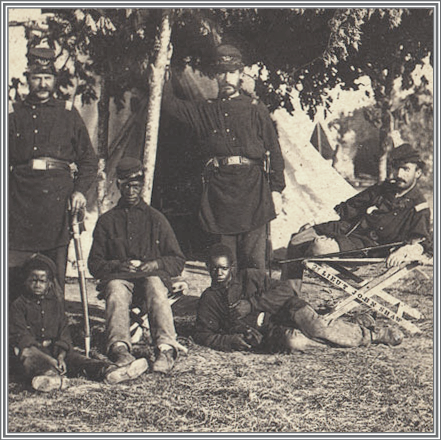

The first African Americans to serve in the army were slaves who ran away from plantations or from Confederate troops to seek refuge in Union army camps. They were considered to be “contrabands,” or “property of the enemy.” These men were used as cooks, drivers, and laborers. Union troops soon realized the value of these workers. During the summer of 1861, the United States Congress passed the first Confiscation Act. This allowed Northern armies to seize any slaves helping the Confederate cause.

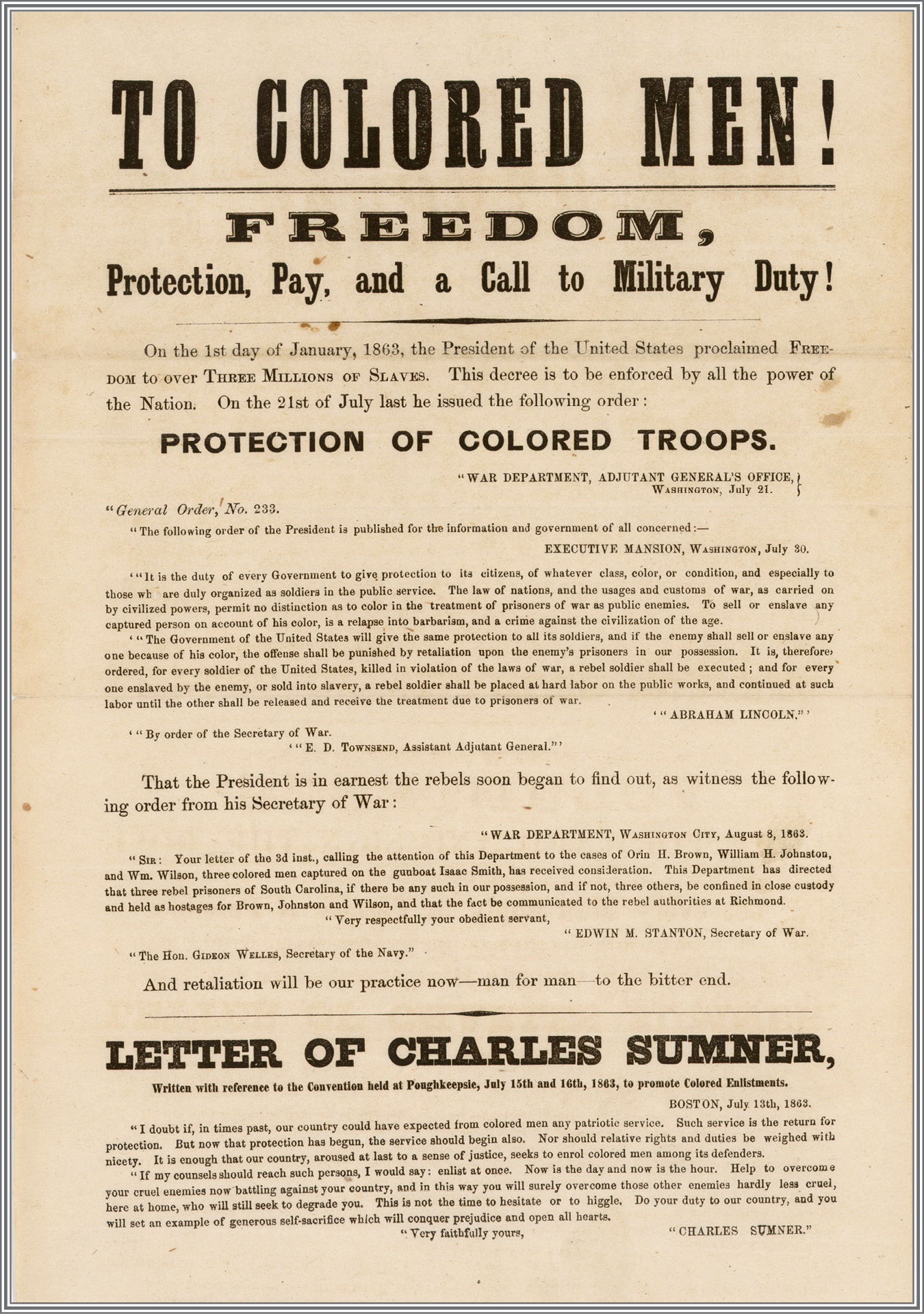

On January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves in most of the states fighting against the Union. Border states such as Kentucky and Maryland were not affected if they declared loyalty to the Union. At the same time, the Union army was given the power to recruit slaves for labor, not for military fighting.

Demand for soldiers caused this policy to change. The war had been dragging on, and the number of white volunteers and recruits was growing smaller. The Northern troops needed reinforcements, so the army gradually looked to African Americans to fill the ranks. In May 1863, the U.S. War Department set up the Bureau of Colored Troops. Its job was recruiting black soldiers. Special posters promised money and freedom to “colored” men who joined the army.

In spite of the desperate need for soldiers, though, most white Northerners did not want to fight side by side with black men. From the beginning, African American soldiers were placed in their own separate units. Nearly all troops were led by white officers. By the end of the war, there were only about eighty black officers among the nearly 190,000 who served.

Pay for black soldiers was not equal to pay for whites. In 1863, the standard monthly salary for a white enlisted soldier was thirteen dollars, plus a three-dollar clothing allowance. Black soldiers were paid only ten dollars a month, and three dollars was deducted from their salary for clothing. In August 1864, Congress passed a law making soldiers' pay equal for all men who were free when the war began. It wasn't until March 1865 that Congress finally passed a law giving all black soldiers pay equal to that earned by whites.

African American soldiers were often assigned “fatigue duty.” This meant that they worked eight to ten hours a day digging ditches, handing out rations, unloading supplies, repairing bridges, and burying the dead. Finally, in June 1864, the War Department issued an order forbidding camp commanders to assign more fatigue duty to black soldiers than to whites. But the new order was hard to enforce.

Camp Nelson was a Union military camp located south of Lexington, Kentucky. Covering over 800 acres, the grounds held more than 300 buildings, including the Soldiers Home, a prison, a hospital, a blacksmith shop, a bakery, corrals, and a laundry. Set up as a supply depot for Union troops fighting in Tennessee, the facility also provided and trained horses and mule teams.

In the Conscriptive Act of February 1864, President Lincoln authorized the use of black troops for the war effort. Kentucky African Americans, free and slave, poured into Camp Nelson to enlist. On July 25 alone, 322 black recruits joined up. The government paid freedmen like Gabriel's father an enlistment fee. Slaves who became soldiers were given their freedom, and some of their former masters were paid three hundred dollars.

Camp Nelson soon became the third-largest recruiting and training center for black soldiers in the country. From November 1864 to April 1865, almost 5,400 Kentucky slaves and freemen enlisted there.

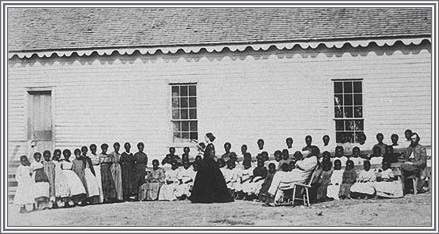

For many of the black recruits, Camp Nelson was their first experience with freedom. These menâand the women and families who came with themâhad a powerful desire to attend school. On July 19, Reverend John G. Fee established the Camp Nelson School for Colored Soldiers. “I find them manifesting an almost universal desire to learn; and that they do make rapid progress,” Reverend Fee wrote of his scholars.

During late summer and fall of 1864, when Gabriel and Annabelle were at Camp Nelson, school attendance was high. In one day, an average of 60 soldiers, 30 boys, and 40 young women and girls went to class. After six weeks of working in the camp, Reverend Fee wrote that he had “a very excellent school roomâa good supply of slates books &c.” He also had thirteen eager volunteers like Annabelle to help him teach.

During the Civil War, both the Confederate and Union armies depended heavily upon horses. One of Camp Nelson's biggest responsibilities was supplying horses and mules for the Union troops fighting in Tennessee. The animals were needed to pull wagons, cannons, and ambulances to and from battlegrounds. The horses also carried cavalry soldiers and officers into battle.

About 1.5 million horses and mules died during the Civil War. (Approximately 700,000 soldiers died.) One Union officer reported that Rebel sharpshooters had killed or wounded 500 horses in one day. But not all the animals died in battle. Many of them died from disease, poor food (or no food), poor care, and overwork. Major William Jennens, a Union cavalryman, wrote: “From the 16th of May to the 19th horses were without feed. . . . During this time we traveled thirty-five miles; the last five we traveled at a gallop causing horses to give out by the dozens.”

During the Civil War, the Bureau for Colored Troops recorded only seven black cavalry regiments. In June 1864, officers from Camp Nelson began selecting recruits for the Fifth Colored Cavalry (Gabriel's regiment). Nearly all of the recruits were former slaves. The officers, like the fictional Captain Waite, were white men. Before the regiment was completely organized, it was sent to Saltville, Virginia. Colonel James S. Brisbin traveled with the Fifth as they marched from Kentucky to Virginia.

“On the march the colored soldiers, as well as their white officers, were made the subject of much ridicule and many insulting remarks by the white troops,” Colonel Brisbin reported. “These insults as well as jeers and taunts that they would not fight, were borne by the colored soldiers patiently . . .”

The Fifth lost 114 men (out of 400) and four officers during the battle. Afterward, Colonel Brisbin reported: “Of this fight I can only say that men could not have behaved more bravely. I have seen white troops fight in twenty-seven battles and I never saw any fight better.”

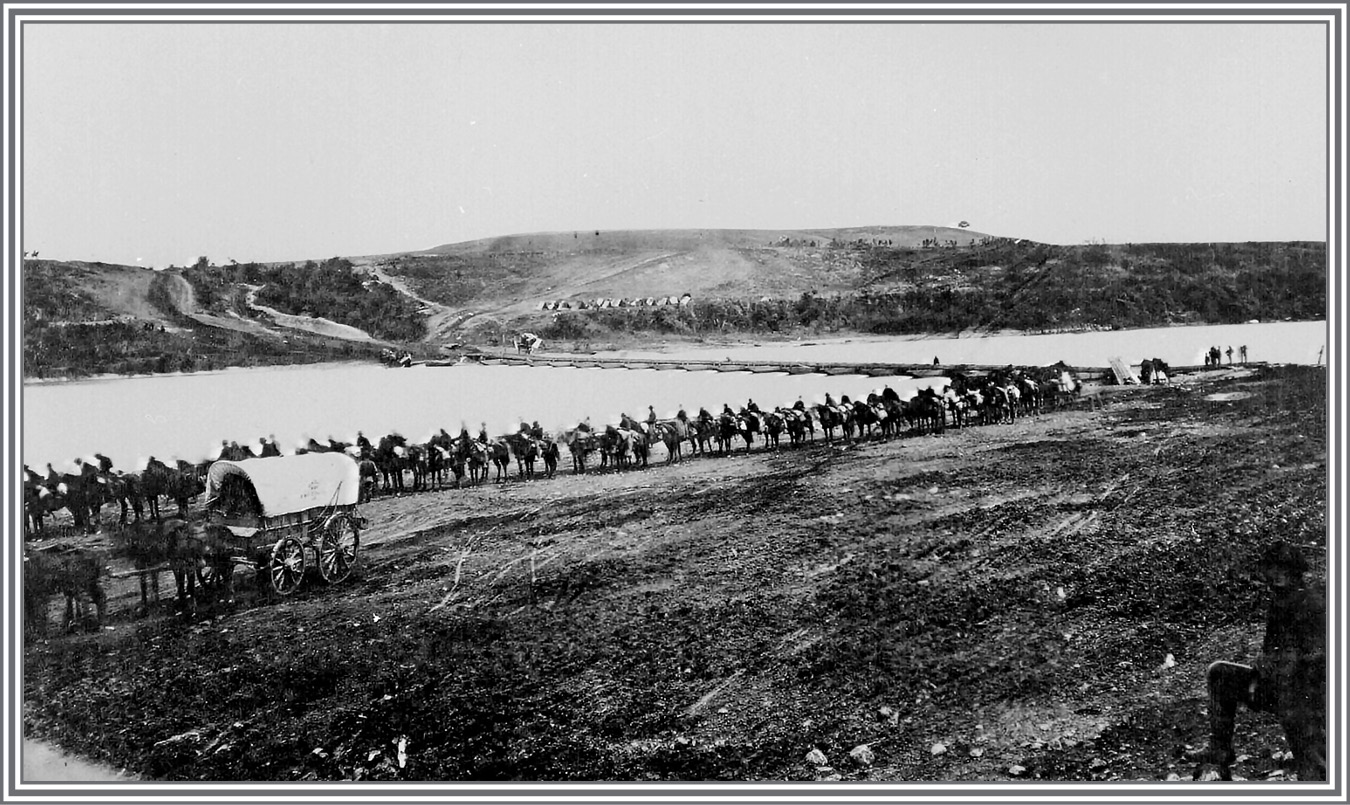

Rappahannock River, VA, 1862