Gallipoli (24 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

And yet ⦠things seem ⦠quiet.

Perhaps a little â¦

too

quiet?

No sooner is the pod of British vessels right in the middle of the minefields than the silent darkness is sliced by a dozen searchlights from the shore, then shattered by the all-too-familiar sound of artillery. Shells start to rain around the ships, sending up great water spouts. From both shores, flashes momentarily illuminate the hillside, soon answered by the return flashes of explosions from

Cornwallis

and the other ships. Meanwhile, the captain of the 3000-ton cruiser

Amethyst

bravely positions his ship to draw fire away from the minesweepers.

With far more resolution than has been shown previously, the tiny vessels keep pushing through the minefield. Unfortunately, at the turning point above the field there are just two trawlers still capable of operating, at which point the shells landing around them become so concentrated that it would have been nothing more than suicide to remain, and they start to retreat hastily.

At just this moment,

Amethyst

suffers two direct hits, killing 22 men, with many more critically wounded. So devastating is the explosion that the bodies of the dead, chiefly on the mess deck, are blown into so many pieces that the remains have to be collected in sacks and an attempt made to work out which parts went with which. Three men have been killed on other boats.

Some mines have indeed been culled, but the sober truth remains: the minefield barrier is essentially undiminished and remains as much a killing field as it ever was.

At least the British know one thing: with their best efforts, they cannot get the job done in this way. Though Keyes himself remains undaunted, Carden reluctantly decides on a change in tactics â a change as stark as the difference between night and day. Henceforth, he will send the sweepers into the Kephez minefield in bright sunshine only, after the forts that have been so hammering them are themselves bombarded.

Carden is devastated by the number of men lost in the engagement, and his feelings are little salved by a cable from Winston Churchill the morning after the failed attack, in reference to the

previous

failures:

I DO NOT UNDERSTAND, WHY MINESWEEPERS SHOULD BE INTERFERED WITH BY FIRING WHICH CAUSES NO CASUALTIES. TWO OR THREE HUNDRED CASUALTIES WOULD BE A MODERATE PRICE TO PAY FOR SWEEPING UP AS FAR AS THE NARROWS ⦠OPERATION SHOULD NOW BE PRESSED FORWARD METHODICALLY AND RESOLUTELY AT NIGHT AND DAY. THE UNAVOIDABLE LOSSES MUST BE ACCEPTED. THE ENEMY IS HARASSED AND ANXIOUS NOW. TIME IS PRECIOUS â¦'

61

TESTING THE WATERS

Arthur Balfour: âConsider the casualties. There must have been nearly 10,000 men lost in these engagements.' Lord Kitchener: âEight thousand seven hundred at Neuve Chapelle, but it isn't the men I mind. I can replace the men at once, but I can't replace the shells so easily.'

1

Conversation recorded in the diary of Frances Stevenson, 4 April 1915

15 MARCH 1915, DARDANELLES, A TALE OF SMOKE AND SEWER PIPES

Driving along the road that lies by the sparkling Dardanelles on this gorgeous spring morning, the host of the American Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, Major-General Cevat â the Turkish Commander of the Fortified Defences at the Dardanelles â points out with great pride the minefields across the Narrows, now boasting no fewer than 400 mines.

Ah, but, Ambassador, you have not heard the best part. For many of these mines â blocking the Russians from coming south and the British from coming north â have come from the Russians themselves!

With great gusto, Major-General Cevat tells the man from New York how every day at the Black Sea entrance to the Bosphorus, Russian destroyers release mines, hoping they will float downstream to blow up Turkish ships â or even one of the German warships â and how, every day, Turkish and German minesweepers âgo up, fish out these mines, and place them in the Dardanelles'.

2

With every passing week, the defences of the Dardanelles are getting stronger.

The Turkish General goes on to outline the situation of their forts' guns, their recently acquired mobile howitzers and a number of other innovations. On that note, he summons forth a Sergeant, who leads the Ambassador over to a contraption that is no more than an elongated section of sewer pipe. But, as the excited Turks begin to explain, it is so much more than that. Communicating by telephone with those operating the howitzers, the Sergeant is quite capable of discharging this sewer pipe, filled with useless gun powder, at exactly the same time as the howitzers, and so attract â courtesy of the âconspicuous cloud of inky smoke'

3

â at least his fair share of the ships' shells. The proof is the heavily pockmarked ground all around the Sergeant's faux gun, and Morgenthau is proudly told that the whole ludicrous contraption had attracted no fewer than 500 useless shots.

Lunching back at the Major-General's headquarters, Cevat and Ambassador Morgenthau are joined by three high-ranking officers, including Admiral Guido von Usedom, the man most responsible for strengthening the Turkish defences using German know-how. Most striking to Morgenthau is the officials' total confidence. âWhat they seemed to hope for above everything,' the American would note, âwas that their enemies would make another attack.'

4

They simply cannot wait â and the bigger the attack, the better.

One eager German pines for one thing above all else. âIf we could only get a chance at the

Queen Elizabeth

!' he declares, referring to the mightiest ship in the British armada.

Ah, but this is still not enough for one of the other military men as the wine continues to flow, and Ambassador Morgenthau ever after recalls his exact words: âIf the damn fools would only make a landing!'

5

15 MARCH 1915, TENEDOS, âTHERE IS A TIDE IN THE AFFAIRS OF MEN, / WHICH, TAKEN AT THE FLOOD, LEADS ON TO FORTUNE; / OMITTED, ALL THE VOYAGE OF THEIR LIFE / IS BOUND IN SHALLOWS AND IN MISERIES â¦'

6

And sometimes life's flood heads in the wrong direction, the back-rushing midnight waters filled with disaster after disaster â¦

It is not quite clear whether 57-year-old Vice-Admiral Sackville Carden is suffering from nervous exhaustion, an explosive ulcer or the consequences of a âbeastly suet and treacle pudding' he had eaten the day before.

7

Regardless, the upshot is the same.

After a sleepless night drowning in the horrors of the responsibilities of war, taking 80,000 men and over 200 vessels into the jaws of hell that lead to the murderous minefield â a plan that runs directly contrary to his desires â his aides find Carden that morning simply incapable of functioning. All he can get out in his highly disturbed state is that he simply cannot go on.

The Admiralty is advised, and, with relief on both sides, Carden is relieved of his command. He is replaced by Rear-Admiral John de Robeck â now promoted to Acting Vice-Admiral â a 52-year-old veteran of the Royal Navy.

Having raised his flag aboard

Queen Elizabeth

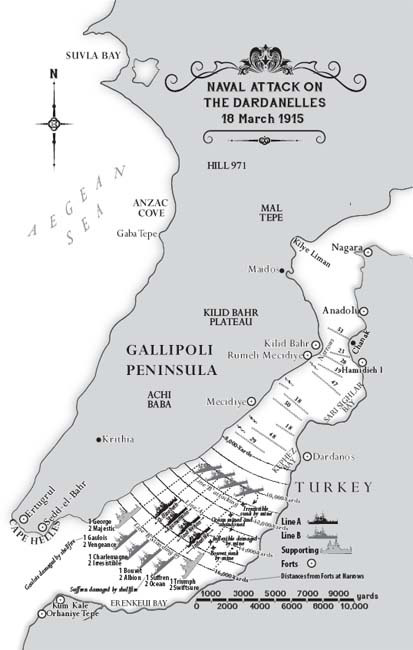

at Tenedos, de Robeck reviews Carden's plan for the attack. In 48 hours' time, three lines of British and French battleships â Lines A, B and C â will enter the Dardanelles, each wave in its turn and at an ever closer range, bombarding the intermediate forts and batteries either side of the Straits. Once these are neutralised, minesweepers will be sent forward to clear the waters, allowing the battleships to progress, if all goes well, all the way to Constantinople.

Despite having an uncommon old-world courtesy about him, Admiral de Robeck commits to the audacious plan to force the Dardanelles by navy alone. (Privately, de Robeck shares the view of all his senior officers: it would be much âbetter to have a combined operation', with the army making a landing. The problem is he has never been âconsulted as to whether it was the right way to do it or not'.)

8

In fact, even many of those who have been consulted are against the one-dimensional attack. One who has watched the Dardanelles campaign with rising concern is War Council Secretary Lieutenant-Colonel Hankey, who writes to Prime Minister Asquith on 16 March:

From the point of view of the War Council the situation as regards the attack on the Dardanelles is far from clear ⦠As recently as the last meeting the War Council were informed by the First Lord that the navy still hoped and expected to get through the Dardanelles without the assistance of military forces. Now, however ⦠the employment of a considerable land force is contemplated â¦

It must be remembered that combined operations require more careful preparation than any other class of military enterprise. All through our history such attacks have failed when the preparations have been inadequate, and the successes are in nearly every case due to the most careful preparation beforehand ⦠It must be remembered also that one of the greatest advantages to be obtained from this class of operation, namely, that of surprise, has been lost ⦠It is suggested that the War Council ought to cross-examine the naval and military authorities on the extent of the preparations â¦

Unless details such as these are duly thought out before the landing takes place, it is conceivable that a serious disaster will occur.

9

Prime Minister Asquith?

He does indeed ask Lord Kitchener about one point raised â has a scheme for a land invasion been worked out? â and is satisfied when Kitchener responds that he has insufficient information on the subject, and such matters âmust be left to the commanders on the spot â¦'

10

Then he gets back to writing a note to lovely Venetia.

MID-AFTERNOON, 17 MARCH 1915, TENEDOS, HAMILTON PARKS HIS PHAETON

Yes, it has been a frantic trip, but what a destination!

General Hamilton and his senior staff are pacing the quarterdeck of the sleek cruiser

Phaeton

, looking out upon the sparkling, impossibly blue waters of the Aegean Sea, when the captain suddenly turns the wheel to starboard and they steam through the white-cliffed heads of Tenedos Harbour, where the vista that meets their eyes is like manna from heaven.

For here, in this lovely wilderness, as one senior officer would recount, âthe bristling, threatening world of a British battle fleet burst upon our astonished view ⦠As we paced the tiny quarterdeck of HMS

Phaeton

, throbbing from stem to stern, who thought of failure? Not the Chief, certainly.'

11

18 MARCH 1915, DARDANELLES, MONSTERS IN THE MIST

And so it has come to this. After all the meetings, all the cables, all the prevarications and posturing, all the deep poring over maps and compilation of battle plans, on this morning, when the fog of war is both metaphorical and real, 12 British and four French battleships weigh anchor at 7 am. From their base at Tenedos, they soon get up a full head of steam and begin their assault on the Dardanelles. Glory be to the Empire, and let us see if we can put the fear of God and old England into the hearts of the heathens!

Along with

Inflexible

, the up-to-the-minute pride of the fleet,

Queen Elizabeth

, glides imperiously at the head of the flotilla, the tip of the spear. Her guns are bristling, her superstructure is shining, and upon her bridge Acting Vice-Admiral John de Robeck's jaw is set.

Naval attack on the Dardanelles, 18 March 1915, by Jane Macaulay

The other battleships, formidable in their uniform grey garb, settle into their positions a little to the aft of their leaders' starboard and port, each one attended by a patrol boat assigned to go just in front and ward off any floating mines. Bringing up the rear are the vital minesweepers.

Surely the only entities unimpressed are the weary white peaks of Asia â peering down upon the aquatic cavalcade as they pass â having seen this all before, so many, many times.

As the morning mist starts to lift, a young Turkish soldier, looking out from an observation post at the top of a hill just south of Kum Kale, sees something. Definite shapes are emerging. Ships!

War

ships!

It is nothing less than the â[Imperial] Fleet making manoeuvres â¦'

12

Barely daring to believe his eyes, he watches carefully as the fleet turns and starts to charge towards the opening of the Straits! He immediately picks up the telephone and sends out the word: the infidel attack they have been so long preparing for has finally arrived.

News of the oncoming armada quickly spreads among the Ottoman ranks. Orders are barked and bells are rung. Officers and troops rush to their positions. As they do so, âthe sound of the morning's call to prayer,

Allahu Ekber,

rises up into the sky,'

13

reminding each soldier of the solemn duty before them. Even at the cost of their lives, they are to defend their homeland, in the name of Allah.

The Turks are relying foremost on the mines to defend them from a major incursion into the Straits, but the 14 old forts that line the waterway, boasting 82 guns in fixed positions, also have an important role to play. Just back from them are the 230 mobile guns and howitzers that are to aid them.

A little south of Kilid Bahr Castle, the 15th-century fortress standing across from the town of Chanak, the commander of the Rumeli Mecidiye Fort, Captain Hilmi, calls for his men, now huddling together for warmth, to gather. After issuing his orders, the commander adds, âNo one will bother with the dead and wounded. If I die, walk over me, and just pass. And if I get wounded, pay no attention. I will do the same with you. Those who will replace the wounded and the dead have been determined. Don't expect any rewards in war. This, I will not and cannot promise.'

14

Among the men walking away purposefully from the commander is Corporal Seyit, a tough, bald, squat timber chopper, renowned in his nearby village for his great strength. He is in command of one of the L/35 Krupp Fortress ten-inch guns. Under orders from Captain Hilmi, they are all to hold fire until the ships are within range. And then they are to unleash hell.