Gallipoli (67 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

Unable to see whether the barrage is having any effect, the on-edge Turks continue to fire wildly, and are confused when they hear cheers. The Australians seem unaccountably to be enjoying the tumult, their cries being carried by the wind to bounce off the cliffs, somersault and soar up towards the heavens.

To add to the uproar of the Turkish artillery, now an Indian mountain battery sends star-shells at them, which soon set fire to the scrub near Lone Pine. The night is filled with explosions, flaring flames, choking smoke, billowing dust and yes ⦠still cheers.

And yet one Turkish shell actually does land close to a bullseye, claiming 22 casualties in the 8th Light Horse Regiment, of whom seven are killed. (Among the wounded is none other than Colonel Alexander White, who takes a flesh wound to the skull when hit by a fragment of shell.)

Has such a disaster weakened the Australians' resolve in any manner? Has it

hell

. Though the losses are tragic, they are insignificant in terms of overall numbers, and so it is that the 8th Light Horse is still there in force as midnight of 29 June approaches and Mustafa's 18th Regiment is given the final order to attack.

The barrage suddenly stops, and the inevitable cry of â

Allah! Allah! Allah!

' rises up, followed by wave after wave of Turkish soldiers running down the slope from the Nek to Russell's Top, across the exceedingly narrow spine of land that connects them.

And therein lies the problem for the Turks. So narrow is the razor-back ridge that they have no capacity to outflank the Australians and instead must run tightly packed together â meaning that the 8th Light Horse just can't miss.

âOur men,' Trooper Ernie Mack would recall, âsat right up on the parapets of our trenches and when not firing were all the time calling out for the Turks to come along and hooting and barracking them. In fact most of the chaps took [it] as a real good joke.'

80

Yes, one or two Turks make it to the Australian trenches, but that is nothing that a few quick thrusts of the bayonet can't fix. And at another point, some 50 Turks actually occupy one of the saps and push forward but, again, they are soon forced out by a concerted drive of soldiers.

The most amazing thing is that this goes on for almost

two hours

before the Turkish 18th Regiment is defeated everywhere. By pursuing the sheer insanity of crossing this narrow bridge of land into massed Australian guns, a battalion and a half of the Ottoman's 18th Regiment is wiped out, with 260 dead,

81

while the Light Horse lose only seven men killed and 19 wounded.

This has been a bad blow for Colonel Mustafa â not helped by the fact that General Enver is still on the scene at Kemalyeri, from where he witnesses the devastation firsthand. No good news has come back from the front this night.

They have not taken Russell's Top. They have not pushed the enemy into the sea. Despite General Enver's assurance to the shattered and scattered surviving men of the 18th that their efforts had been âmost useful in engaging the attention of the English at a critical moment',

82

a question mark is placed firmly over Mustafa's judgement and ability to command the Ari Burnu sector.

The disaster notwithstanding, still the Turks keep pressing the Anzac lines in coming days, and though the battles at this time are not nearly as ferocious as early in the campaign, still the Australians and New Zealanders see a steady stream of dead and wounded coming back from the frontlines.

In one particular battle in early July, Trooper Bluegum again finds himself in the thick of it on Holly Ridge, at a point where the Turks land some 200 shells on their trenches in just a few hours. Most of the men keep their heads down, but one of their number, Sergeant Fred Tresilian, a Boer War veteran originally from down Wagga Wagga way, appears to relish it. â[Fred] seemed to love the firing-line like home,' Bluegum would record. âHe was quite fearless. Somehow he seemed to revel in the roar of battle.'

83

And so it is on this occasion. When the Turks drop no fewer than a dozen shells right on the tiny ANZAC section of trenches, carnage results, as the parapet is blown apart, as is most of the trench itself. Those not killed are wounded, blinded, buried, choked, deafened or all of the above. One of the last is Trooper Bluegum, and when he can finally see and hear and breathe again, the first person he encounters is Sergeant Fred Tresilian, laughing merrily.

âHello, Bluegum,' he says, easy as you please, ânot killed yet?'

84

For his part, Bluegum is

not

surprised to see the Sergeant not killed yet, as despite having volunteered for some of the riskiest scouting and patrol work, he somehow seems to avoid all the bullets. But can it last?

Perhaps. And yet, only ten days later, when still one more battle breaks out, a bullet comes so close it actually nicks Tresilian's cheek.

He's done it again!

A short time later though a sniper's rifle cracks and a bullet comes and drops Tresilian dead.

Such is life, and death, at Gallipoli.

THE BATTLE IS NIGH

I stick to what I wrote to Wolfe Murray: the combination of Stopford and Reed is not good; not for this sort of job.

1

General Sir Ian Hamilton, Gallipoli Diary

Hamilton has not the strength to give those with whom he is surrounded a straight out blow from the shoulder â however much the situation demands it. To mix the metaphor â he has an unlucky ability for gilding the pill. He can't administer a pill unless it is golden â¦

2

Charles Bean on General Hamilton

MID-JULY 1915, IMBROS, SHHHHHHHH, THE PLAN IS PERFECTED

That hush around General Hamilton in these dog days of mid-July? It's the sound of fresh divisions

finally

starting to arrive, as he and his senior staff work on the finer details of their secret plan to finally and properly seize the Dardanelles â a plan so sensitive and so vital it must be kept from getting out at all costs, and so is kept âwithin a tiny circle'.

3

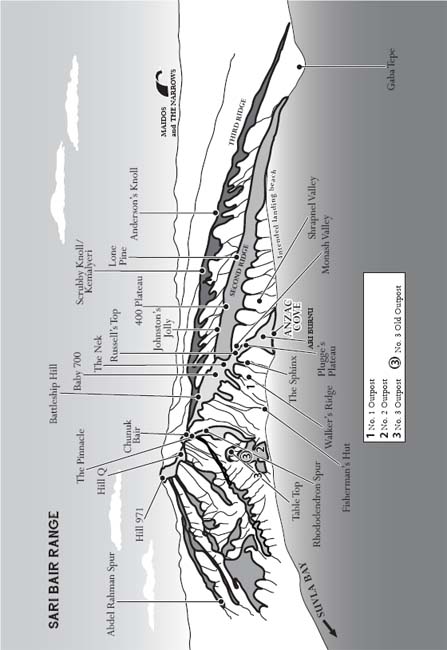

The Commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force has accepted the logic of General Birdwood's plan, that with just one more Division he could break out of Anzac and seize the heights of the Sari Bair Range.

Not that General Hamilton is expecting it to be that easy.

âAs to our tactical scheme for producing these strategical results,' he astutely notes in his diary, âit is simple in outline though infernally complicated in its amphibious and supply aspects.'

4

Sari Bair Range from the shore, by Jane Macaulay

In short, a multi-faceted assault is planned, across a wide front, with each successive attack depending on the one next to it to succeed or, like the weakest link in the chain, the whole thing risks breaking down.

The French and British forces at Cape Helles will launch their attack so as to draw the attention and resources of the Turks to the south. It will be sustained for precisely as long as it takes to burn through the 4000 soldiers that GHQ has calculated as surplus to requirements â cheers, lads.

5

So, too, will the Australians make an attack at Lone Pine ââthe crown of the 400 Plateau'

6

â the key post right in the middle of the ANZAC front. This heart-like crown is divided by Owen's Gully into two lobes: the northern Johnston's Jolly, and the southern Lone Pine.

There, where the trenches are anywhere from 50 to 100 yards apart, the plan is relatively simple. After a long bombardment, the Australians and New Zealanders will simply charge forward and take over the forward trenches. Once the Turks know that there is a serious attack here, they will inevitably call in forces from elsewhere, including from the peaks of the Sari Bair Range â the troops stationed around Chunuk Bair, Hill Q, Hill 971, Battleship Hill and Baby 700 â which is where the next part of the plan comes into play.

For, after Lone Pine is secured and the Turks from on high come forward, under the cover of darkness and distraction the Right Covering Force of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade are to stealthily make their way through the least defended part of the perimeter, at the far north, and knock out the thin defences leading up to the heights of the Sari Bair Range. In particular, they are to overwhelm the significant Turkish enclave known as Old Number Three Outpost, which stands guard over the entrance to Sazli Gully (the place Mustafa Kemal had pinpointed to his superiors just over a month beforehand). Altogether, the Right Covering Force is to be around 1900 men.

7

A Left Covering force is, in principle, to do the same but will take a wider left hook, north from the Anzac Sector, and clear a path for an approach to Hill 971 via a small indent in the land called Aghyl Gully.

Shortly thereafter, two columns of troops, totalling 10,000 men, would also move out of the ANZAC perimeter. The Left Assault Column â commanded by Major-General Vaughan Cox with his 29th Indian Brigade and assisted by the newly promoted Brigadier-General John Monash with his 4th Brigade

8

â would first head north along the northern beach road and then turn right, trekking and fighting their way through the night, up Aghyl Gully then climbing and fighting all the way to the summits of Hill 971 and Hill Q before dawn. The Right Assault Column, all men of the Shaky Isles under Brigadier-General Francis Johnston (Commander of the New Zealand Infantry Brigade), will head east from the Number Two Outpost, following the route of the covering force before them, then break into two groups to trek and climb and fight their way to the summit of Chunuk Bair.

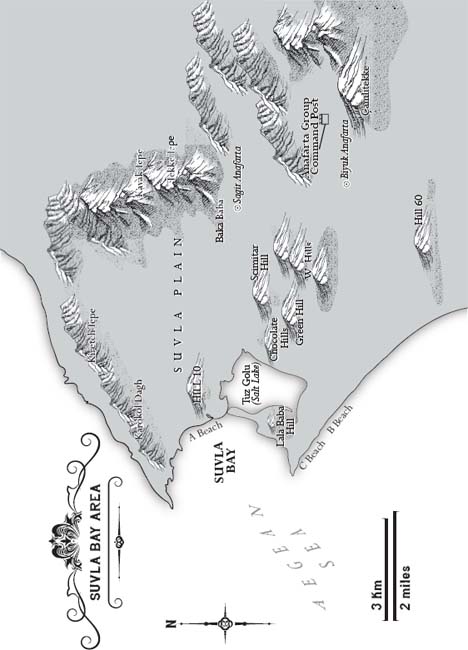

While all this is going on into the night, two new British Divisions will arrive on the shores of Suvla Bay, some four and a half miles to the north of Anzac Cove.

The actual landing spot is a large plain, dominated by a dried salt lake, flanked on three sides by hills beginning around three miles from the shore. The first of these British forces â 18,000 strong of the 11th Division â are to sweep south-east, across that plain and up to the surrounding ridges as swiftly as possible, to occupy the high ground leading up to the Anafarta villages and Sari Bair Range before daylight. âOf first importance' will be the taking of Chocolate Hills and W Hills before daybreak,

9

which will hopefully lead on to the taking of the village of Big Anafarta.

At daybreak, they will be followed along the ridge line by two brigades â 8000 soldiers â who have landed after them. From here, if required, these troops will be in a position to advance along the eastern spurs of Hill 971, which would link them with elements of the Left Assault Column of the ANZAC breakout.

And then, the denouement. By dawn the following morning, the two columns atop Hill 971 and Chunuk Bair will be in position to attack the Turks dug in on Baby 700

from behind

, and at this moment the men of the 8th and 10th Light Horse will attack the Nek in four waves of 150 soldiers each.

Suvla Bay area, by Jane Macaulay

The Turks, attacked from in front and behind, will fall away, and Baby 700 will be captured. If the taking of Chunuk Bair from the rear is delayed for any reason, the attack on the Nek and Baby 700 will nevertheless proceed, acting as a feint if nothing else.

Oh, and, as Bean would note, âsimultaneously the 1st Light Horse Brigade, [which was] then holding Pope's and Quinn's, was to seize with its 1st Regiment a part of the Chessboard and with its 2nd a sector of the Turkish Quinn's'.

10

All clear?

Not really.

Then let's go through it again.

And so General Hamilton and his senior officers do, again and again and again, trying to refine the plans and define the goals, to the point that every individual unit across the 90,000 soldiers involved would be given specific orders to go after clearly designated targets, and on a very strict timetable.

It really is dreadfully complicated, but, if all goes well, by the conclusion of the battle the Allies will be in control of all the high ground from Ejelmer Bay in the north through Chunuk Bair and along to Gaba Tepe. They will have finally secured the heights of the Sari Bair Range, which was their target on the day of the landing and was momentarily in their grasp, before Colonel MacLagan had taken the decision to reinforce the Second Ridge.

Having Suvla Bay will give the Allies their own port to get them through the winter, and if all goes really well they will be able to break free of the dreadful confines of the Gallipoli Peninsula and march on Constantinople.

True, there are naysayers to the plans within the tight circle, pointing out that âthe ground between Anzac and the Sari Bair crestline is worse than the Khyber Pass'

11

â as many British officers would know, as they had been there â but General Hamilton is not particularly concerned. It is the strong reckoning of both Generals Birdwood and Godley that their men can do it, and that is good enough for him. â[A]fter all,' Hamilton notes in his diary, âis not “nothing venture nothing win” an unanswerable retort?'

12

Not for the newly arrived Commander of the AIF 1st Division it isn't.

Major-General James Legge â a one-time brilliant barrister who had gone on to pioneer the Military Training Scheme â is convinced that in his sector the plan to attack Lone Pine will see the slaughter of many Australians for little gain. He makes no bones about saying this, just as he had been a critic of the whole landing at Gallipoli in the first place. He feels that the Turkish trenches at Lone Pine are far too heavily defended for the Anzacs to be able to seize them without suffering extraordinary losses.

But Birdwood insists. It is

because

Lone Pine is so key to the Turkish defences that he wants to attack it, because only an attack on such a crucial point would force the Turks to move their reserves there, leaving them unavailable to oppose the main attacks at Chunuk Bair and Hill 971.

Another critic is Colonel Cyril Brudenell White, Chief of Staff to Birdwood, who thinks the plan is fraught with danger from the first, and rather more delicately says so.

But what can Legge and Brudenell White do? A year earlier, to the day, the Australian Government had signed over control of Australian soldiers to the British Government and,

ipso facto

, their officers, so it really doesn't matter what some of the leading Australian officers on site think about the likely fate of their soldiers.

General Birdwood is the Commander of the Anzacs, and General Hamilton the Commander of all the forces on the Peninsula. They are English and they decide what happens to Australian forces. And this, make no mistake, is what both Generals Hamilton and Birdwood want, as with their staff they continue to refine the orders. With all the fresh divisions arriving in the Dardanelles, Hamilton is even starting to feel confident of a breakthrough. âIt seems likely,' he writes, âthat during the first week of August we may have 80,000 rifles in the firing line striving for a decisive result â¦'

How many are likely to be killed and wounded in such an attack?

âQuite impossible to foresee casualties,' he notes, âbut suppose for example, we suffered a loss of 20,000 men; though the figure seems alarming when put down in cold blood, it is not an extravagant proportion when calculated on basis of Dardanelles fighting up to date â¦'

13

Exactly. When judged against the catastrophic casualty figures to date â the losses at the landing, or the three battles for Krithia â just how bad could the âAugust Offensive', as it has become known, really be?

It is perhaps inevitable that, at this time, the ubiquitous Charles Bean gets wind of the whole plan. One day in mid-July, his brother Jack â who has just returned from hospital at Alexandria â has popped over to his dugout for a lunch of bread, tea and flies. Afterwards Charles accompanies him back to the 3rd Battalion HQ so he can write up his notes on what Jack's mob had done in the first three days after the landing. As they weave around groups of chattering men, Jack is impressed at his brother's apparent new-found popularity with the soldiers, who wave and nod with respect.

When they arrive at Jack's camp, Bean hears talk for the first time of a big attack to be launched in early August â¦

It worries him. For if he is hearing about it like this, so casually mentioned, with everyone living on top of everyone else, how long can it be before it is general knowledge and the enemy finds out too?

Of more concern to Birdwood than simple security, however, is the overall health of the veteran ANZAC troops, as no fewer than 200 men a day at Anzac Cove alone are now being evacuated through sickness, and those who remain are teetering on it. Oh yes, Birdwood knows all that, all right. As he walks around the trenches, he is frequently told by the men, âNo Turk is going to get past here â I'll see to that: but if you asked me to march a couple of miles after him, I just couldn't do it.'

14

And there is also a problem with morale in certain sections, with the practice of âmalingering' â staying in hospital well past the point of recovery â on the rise.

Another sign is a warning from the Chief Staff Officer of the 1st Australian Division, Colonel White, that he has become aware of âincreases of wounded men sent down to the base hospitals with the remark “self-inflicted”'.

15

It is a real problem, and one getting worse with the passing weeks.