Georgian London: Into the Streets

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

Lucy InglisGEORGIAN LONDON

For Richard, with love

‘The web of our Life is of a mingled Yarn’

St Paul’s Cathedral destroyed by the Great Fire, 1666

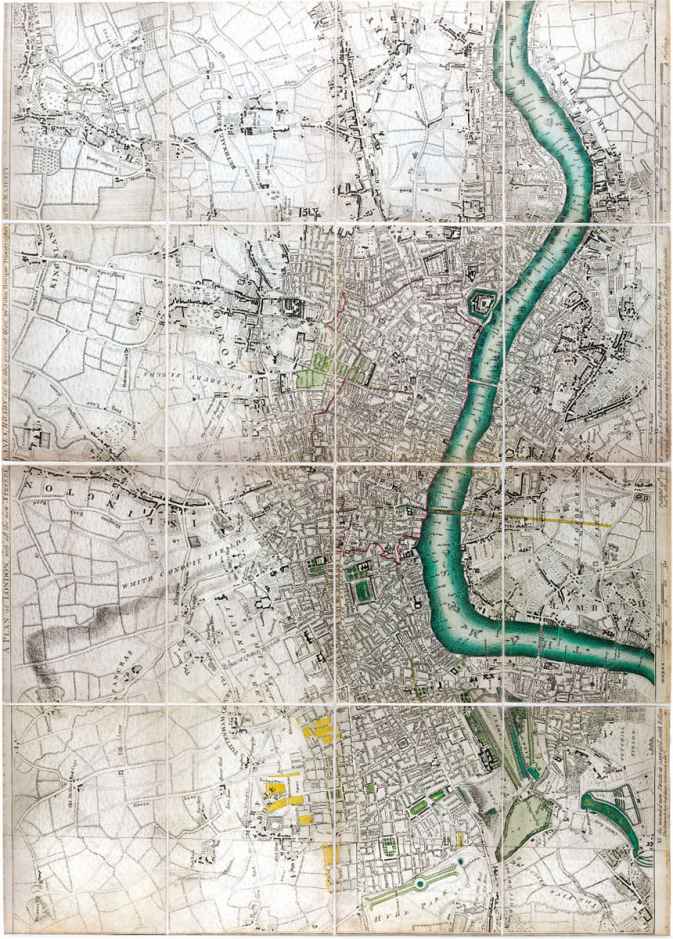

St Paul’s and surrounding area, 1745

The Bank of England and Royal Exchange, 1745

Moorfields and the Artillery Ground, 1745

Holborn, Lincoln’s Inn and Temple, 1790

The remains of Gibbon’s Tennis Court, 1809

Westminster, 1827 (

Motco Enterprises Ltd

)

‘Love and Dust’, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1788

St James’s Square and surrounding streets, 1745

Covent Garden and the Strand, 1745

The trade card for Mrs Holt’s ‘Italian Warehouse’

Advertisement for Mozart’s appearance in London, 1765

The Huguenot Pezé Pilleau’s trade card, 1720

‘The Dying Gaul, or Smugglerius’ (

Fitzwilliam Museum

)

Mayfair, 1827 (

Motco Enterprises Ltd

)

Advertisement for the Hindostanee Coffee House, 1811

Marylebone Pleasure Gardens, 1745

Southwark, 1827 (

Motco Enterprises Ltd

)

Eleanor Coade’s stone factory, Lambeth, 1784

Spitalfields and Whitechapel, 1827 (

Motco Enterprises

Ltd

)

Bethnal Green, 1827 (

Motco Enterprises Ltd

)

The Aquatic Theatre, Sadler’s Wells, 1813

1.

William Hogarth, ‘Noon, 1738’, showing a London street scene

2.

St Martin’s Le Grand, the site for the new Post Office

3.

The Jernegan Cistern

4.

Coffee pot made by the silversmith Paul de Lamerie (

Christies, London

)

5.

‘A Paraleytic Woman’ by Theodore Gericault (

Museum of London

)

6.

A view of Marylebone Pleasure Gardens

7.

Dockhead, Bermondsey, showing the notorious slum of Jacob’s Island (

London Metropolitan Archives

)

8.

Castle’s Shipbreaking Yard (

London Metropolitan Archives

)

9.

The Yard of the Oxford Arms Inn, Ludgate Hill (

London Metropolitan Archives

)

10.

Capper’s Farmhouse being slowly consumed by Heal’s, Tottenham Court Road (

London Metropolitan Archives

)

11.

‘The Tower of London’, engraving by William Miller after J. M.W. Turner

12.

‘New London Bridge, with the Lord Mayor’s Procession Passing Under the Unfinish’d Arches’

13.

‘Southwark Bridge from Bank Side’

14.

‘Wapping Old Stairs’

15.

‘The five orders of Perriwigs as they were worn at the late Coronation measured Architectonically’

16.

‘The Fellow ‘Prentices at their Looms, Representing Industry and Idleness’

17.

‘The Frost Fair of the Winter of 1683–4 on the Thames, with Old London Bridge in the Distance’ (

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, USA /Bridgeman Art Library

)

18.

‘Mr. Lunardi’s New Balloon, 29 June 1785’ (

Science Museum, London, UK / Bridgeman Art Library

)

19.

‘Christie’s Auction Room’

20.

‘Watch House’: the interior of St James’s Watch House

21.

‘The Hall and Stair Case of the British Museum’

22.

The Portland Vase (

The British Museum, Collection of the Dukes of Portland; purchased with the aid of a bequest from James Rose Vallentin, 1945. Photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen

)

23.

‘Workhouse’: the interior of St James’s Workhouse

24.

Tokens given by mothers to their children (

The Foundling Museum, London/Bridgeman Art Library

)

25.

‘View of St. James’s from Green Park, London’ (

London Metropolitan Archives, City of London/Bridgeman Art Library

)

26.

A Spitalfields silk waistcoat

27.

‘The Rhinebeck Panorama’ (

Museum of London

)

28.

‘A View of the London Docks, 1808’ (

Museum of London

)

29.

‘Entrance to the Thames Tunnel, 1836’ (

London Metropolitan Archives, City of London/Bridgeman Art Library

)

30.

‘A View of the Highgate Archway, 1821’ (

London Metropolitan Archives, City of London/Bridgeman Art Library

)

I do not pretend to give a full account of all things worthy to be known, in this great city, or of its famous citizens … but only the most eminent which have occurred to my reading or observation.

Thomas de Laune,

The Present State of London

(1690)

Fourteen years ago I arrived in London to work for an antiques dealer. The city fascinated me, its history hanging in the air like a salty tang. My days were spent amongst eighteenth-century objects, from milk jugs to gold boxes. Who had made them? Where did they live? What were their lives like? In looking for answers I found tales of men, women, children, wealth, crime, poverty, the erotic, the exotic and the quiet desperation of the mundane.

Monarchs, politicians and aristocrats grab the historical limelight, but the ordinary people were my quarry: the Londoners who rode the dawn coach to work, opened shops bleary-eyed and hung-over, fell in love, had risky sex, realized the children had head lice again, paid parking fines, cashed in winning lottery tickets, fought for good causes and committed terrible crimes. Behind their stories, I saw modern London emerge between the Restoration of Charles II and the arrival of Queen Victoria on the throne.

One Sunday, in the summer of 2009, I stood on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral and listened as the bells called to worshippers and tourists alike. People loitered chatting, or climbed the steps and went inside. I imagined this clamour was almost exactly the same as it had been three centuries ago. I recorded it on my telephone and walked home.

For years I had dragged my husband to churchyards, houses, demolition sites, public monuments and hidden memorials, telling him the stories of people long dead: cabinetmakers, slaves, domestic servants, weavers, chimney sweeps and prostitutes. Back at home I played him

the recording, my precious moment of shared experience with Londoners of the past. His dry recommendation was to start blogging the tales I had accumulated and what I believed about Georgian London (perhaps hoping to deflect my endless enthusiasm on to the miasma of the World Wide Web). The blog gained instant traction as it explored relationships, crime, literature, disability, personal hygiene, jobs, sexuality, charity, sport and shopping. This book has sprung from its loins, a tribute to the people of the eighteenth-century city and testimony to the eternal feeling that if I could just run fast enough through London’s endless archives I will catch them, grasp their coat-tails and make them tell me everything about being a Georgian Londoner.