Ghettoside

Authors: Jill Leovy

Ghettoside

is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright © 2015 by Jill Leovy

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

SPIEGEL & GRAU and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Leovy, Jill.

Ghettoside : a true story of murder in America / Jill Leovy.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-385-52998-3

eBook ISBN 978-0-385-53000-2

1. Murder—United States. 2. Homicide—United States.

3. Murder—California—Los Angeles—Case studies. I. Title.

HV6529.L46 2014

364.152’30973—dc23 2013046367

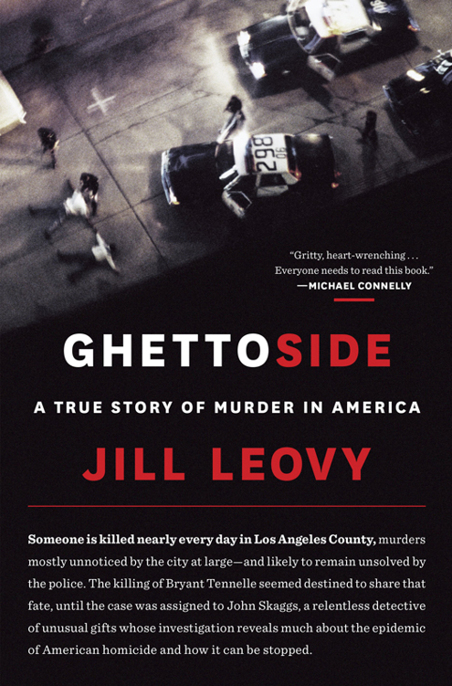

Jacket design: Greg Mollica

Jacket photograph: Ken Schles/GalleryStock

v3.1

When you see the suffering and pain that it brings, you’d have to be blind, mad, or a coward to resign yourself to the plague.

A

LBERT

C

AMUS

,

The Plague

CONTENTS

7. Good People and Knuckleheads

8. Witnesses and the Shadow System

PART II: THE CASE OF BRYANT TENNELLE

12. The Killing of Dovon Harris

23. “We Have to Pray for Peace”

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Notes

Select Bibliography

About the Author

A CIRCLE OF GRIEF

Los Angeles Police Det. John Skaggs carried the shoebox aloft like a waiter bearing a platter.

The box contained a pair of high-top sneakers that once belonged to a black teenage boy named Dovon Harris. Dovon, fifteen, had been murdered the previous June, and the shoes had been sitting in an evidence locker for nearly a year.

Skaggs, forty-four, was the lead investigator on the case about to go to trial.

At six foot four, he was a conspicuous sight in Watts, the southeast corner of the vast city of Los Angeles, a big blondish man with a loping stride in an expensive light-colored suit.

He stepped out of the bright morning light, turned down a narrow walkway along a wall topped with a coil of razor wire, and approached a heavy-duty steel “ghetto door”—a security door with a perforated metal screen of the kind that, along with stucco walls and barred windows, represented one of L.A.’s most distinctive architectural features. He knocked and, without waiting for an answer, pushed the door open.

On the other side of the threshold stood a stout, dark-skinned woman. Skaggs walked in and placed the open shoebox in her hands.

The woman stared at the shoes, choked and speechless. Skaggs’s eyes caught her stricken face as he walked past her. “Hi, Barbara,” he said. “Having a bad day today?”

This was Skaggs’s way, disdaining preliminaries, getting right to the point.

His every move was infused with energy and purpose. In conversation, he jingled his keys, swung his arms, or bounced on the balls of his feet. The movements were not fidgety so much as rhythmic and relaxed, like those of a runner warming up. Forced to hold still in a court proceeding or a meeting, Skaggs would freeze in the posture of a man enduring an ordeal, a knuckle pressed to his lips, a pose that conveyed his bunched-up vigor more than any restless tic.

Now, having deposited the shoes in Barbara Pritchett’s hands—and having received no answer to his question—he came to a halt in the middle of the living room carpet. Pritchett remained silent, head bowed, eyes fixed on the contents of the shoebox.

She was forty-two, in poor health. She had recently been diagnosed with diabetes, and her doctor had urged her to get out and walk more. But her son had been shot to death a few blocks away, and Pritchett was too frightened to venture out. She spent days lying in the dark, unable to will herself to move or speak. That morning, as always, she was wearing a big loose T-shirt with Dovon’s picture on it. All around her, in the tiny living room, were mementos of her murdered son. Sports trophies, photos, sympathy cards, certificates, stuffed animals.

With great care, Pritchett perched the shoebox on the arm of a vinyl armchair by the door and slowly lifted one shoe. It was worn, black, dusted with red Watts dirt. It was not quite big enough to be a man’s shoe, not small enough to be a child’s. She leaned against the wall, pressed the open top of the shoe against her mouth and nose, and inhaled its scent with a long, deep breath. Then she closed her eyes and wept.

Skaggs stood back. Pritchett’s knees gave out. Skaggs watched her slide down the wall in slow motion, her face still pressed into the shoe.

She landed with a thump on the green carpet. One of her orange slippers came off. On the TV across the room, the Fox 11 morning anchors pattered brightly over the sound of her sobs.

Skaggs had been a homicide detective for twenty years. In that time, he had been in a thousand living rooms like this one—each with its large TV, Afrocentric knickknacks, and imponderable grief.

They made a strange picture, the two of them: the tall white cop and the weeping black woman. Skaggs, like most LAPD cops, was a Republican. He would vote for John McCain for president that year. His annual pay was in the six figures, and he lived in a suburban house with a pool. It might be said of him that he was not just white, but a Caucasian archetype with his blond-and-pink coloring and Scots-Irish features. Watts had twice risen in revolt against such an icon—the white occupier-cum-police-officer—and so Skaggs’s presence in this neighborhood was all the more conspicuous for the historical associations it evoked.

Pritchett had a background typical of Watts residents. She was the granddaughter of a Louisiana cotton picker. Her mother had followed the path of tens of thousands of black Louisianans who migrated west in the 1960s, and Pritchett was born in L.A. a few months after the Watts riots. She lived in a federally subsidized rental apartment, and she was a Democrat who would weep in front of CNN later that fall when Barack Obama won the presidential election, wishing her mother were still alive to see it.

Despite their differences, they were kin of a sort—members of a small circle of Americans whose lives, in different ways, had been molded by a bizarre phenomenon: a plague of murders among black men.

Homicide had ravaged the country’s black population for a century or more. But it was at best a curiosity to the mainstream. The raw agony it visited on thousands of ordinary people was mostly invisible. The consequences were only superficially discussed, the costs seldom tallied.

Society’s efforts to combat this mostly black-on-black murder epidemic were inept, fragmented, underfunded, contorted by a variety of ideological, political, and racial sensitivities. When homicide did get attention, the focus seemed to be on spectacles—mass shootings, celebrity murders—a step removed from the people who were doing most of the dying: black men.

They were the nation’s number one crime victims. They were the people hurt most badly and most often, just 6 percent of the country’s population but nearly 40 percent of those murdered. People talked a lot about crime in America, but they tended to gloss over this aspect—that a plurality of those killed were not women, children, infants, elders, nor victims of workplace or school shootings. Rather, they were legions of America’s black men, many of them unemployed and criminally involved. They were murdered every day, in every city, their bodies stacking up by the thousands, year after year.

Dovon Harris was typical of these unseen victims. His murder received little media attention and was of the kind least likely to be solved. John Skaggs’s Watts precinct kept records of scores of such homicides dating back years—shelves and shelves of blue binders filled with the names of dead black men and boys.

Most had been killed by other black men and boys who still roamed free.

According to the old unwritten code of the Los Angeles Police Department, Dovon’s was a nothing murder. “NHI—No Human Involved,” the cops used to say. It was only the newest shorthand for the idea that murders of blacks somehow didn’t count. “

Nigger life’s cheap now,” a white Tennessean offered during Reconstruction, when asked to explain why black-on-black killing drew so little notice.

A congressional witness a few years later reported that when black men in Louisiana were killed, “

a simple mention is made of it, perhaps orally or in print, and nothing is done. There is no investigation made.” A late-nineteenth-century Louisiana newspaper editorial said, “If negroes continue to slaughter each other, we will have to conclude that

Providence has chosen to exterminate them in this way.” In 1915, a

South Carolina official explained the pardon of a black man who had killed another black: “

This is a case of one negro killing another—the old familiar song.” In 1930s Mississippi, the anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker examined the workings of criminal justice and concluded that “the attitude of the Whites and of the courts … is one of

complaisance toward violence among the Negroes.” Studying Natchez, Mississippi, in the same period, a racially mixed team of social anthropologists observed that “the injury or death of a Negro is not considered by the whites to be a serious matter.” An Alabama sheriff of the era was more concise: “

One less nigger,” he said. In 1968, a New York journalist testifying as part of the Kerner Commission’s investigation of riots across the country said that “for decades, little if any law enforcement has prevailed among Negroes in America.…

If a black man kills a black man, the law is generally enforced at its minimum.”

Carter Spikes, once a member of the black Businessman Gang in South Central Los Angeles, recalled that through the seventies police “didn’t care what black people did to each other. A nigger killing another nigger was no big deal.”

John Skaggs stood in opposition to this inheritance. His whole working life was devoted to one end: making black lives expensive. Expensive, and worth answering for, with all the force and persistence the state could muster. Skaggs had treated the murder of Dovon Harris like the hottest celebrity crime in town. He had applied every resource he possessed, worked every angle of the system, and solved it swiftly, unequivocally.

In doing so, he bucked an age-old injustice. Forty years after the civil rights movement, impunity for the murder of black men remained America’s great, though mostly invisible, race problem. The institutions of criminal justice, so remorseless in other ways in an era of get-tough sentencing and “preventive” policing, remained feeble when it came to answering for the lives of black murder victims. Few experts examined what was evident every day of John Skaggs’s working life: that the state’s inability to catch and punish even a bare majority of murderers in black

enclaves such as Watts was itself a root cause of the violence, and that this was a terrible problem—perhaps the most terrible thing in contemporary American life. The system’s failure to catch killers effectively made black lives cheap.