Ghost Sea: A Novel (Dugger/Nello Series) (13 page)

Read Ghost Sea: A Novel (Dugger/Nello Series) Online

Authors: Ferenc Máté

EAR

N

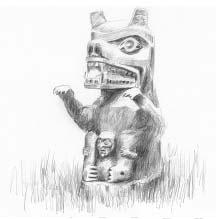

ow I shall press my right hand against your left hand. O friend! Now we press together our working hands that you may give over to me your power of getting everything easily with your hands, friend!

—P

RAYER OF

Kwakiutl bear hunter after the kill

T

he wind had shifted; it came around the point and whipped the smoke of the fire in our faces. Charlie, who had been listening with his eyes fixed on Nello, absorbing if not understanding every word, got up and looked anxiously around for something to clear away and wash, but we had eaten with sticks and our fingers, so he backed shyly toward the woods, said, “Me back soon,” and walked toward a low hole in the brambles.

“Just take care you don’t sit on a bear,” Nello called after him.

The last of the crab claws burnt on the coals; no one wanted them. “There’s water in the creek,” Nello said. “And some nice blackberries.” When we didn’t respond, he went alone to the creek, knelt, and cupped his hands to drink.

The sun beat warmly down. I closed my eyes and, with the breeze and smoke wafting over me, drifted off.

A terrifying bellow shook the air. “Charlieee!” Nello howled. “Bear!” And he lunged head-down, like a madman, through the hole into the woods.

Pumping the Winchester, I ran after him, gasping as I got to the hole where the brambles had been crushed, where, in the silt by a stream, bear tracks glistened, sharp-edged in the sun. I splashed up the creek hearing, “Charlie! Charlie!” up ahead. The cobweb light of the brambles ended and I burst into the forest gloom. Through the wall of cedars the light filtered from the shore, and bowers of colossal firs and hemlocks blocked the sky. There was no undergrowth; the bear trail swept on across the duff of rotted needles.

A cry such as I had never heard, not even in the slaughterhouse of war, rose up ahead.

I ran, leaping over fallen trunks, slipped and fell, holding the Winchester in the air. I found them in a hollow where the air reeked of bear. Nello stood at the foot of a giant cedar, staring up like Mary at the cross, and up on the tree trunk, the body hung slack, facing out. It hung by its white arms a few feet off the ground, the arms extended, its wrists wedged in the branches, the shoulders wrenched, the long hair covering the face, head tilted sadly sideways and down. Nello didn’t move. He stood with his powerful arms crossed strangely on his chest.

I was struck by how well kept were the shoes dangling in the air and how white the shirt, tidily buttoned at the collar. But from the collar down, all the way to where the belt sagged slack and empty from the hips, there was a dark and gaping hollow, a cavern of ribs and shredded flesh. Something that seemed like a part of Nello moved and uttered a strangled sob. Only then did I see he had been holding Charlie, the little face buried in his chest. I looked back up at the body and thought, Thank God it’s over. Tears ran down my face. Nello, still holding Charlie, walked past me and looked up. “The pillow,” he said. “You know him?” I couldn’t reply. “Did you know him?” he repeated.

Whoever he was, with that stubbly beard, he looked tired. The shreds of cedar bark that the bear’s claws had torn into ribbons gave the scene an aspect of festive sacrifice. Only then did I see that his wrists were tied with rope, and in his mouth what had seemed at first like a rolled-back tongue was a roll of cedar bark.

He had been gutted, the soft parts gone. The bear had left only the pelvis and the ribs, and they already swarmed with flies and winding trails of ants. The holster on his belt was still snapped closed.

It occurred to me that I should scramble up and cut him down, give him a decent burial, but the tide was turning, the pass was going slack. I crossed myself and left.

A

RYTHNMIC THUDDING

came from the beach, an aggressive sound, like war drums. And I had both the guns. I ran through the half-light of the brambles and didn’t stop until I was at the gap, looking up and down the beach. The skiff was gone; the drumming was near. I eased myself into the sunlight of the empty beach. Behind a point of brambles, I heard the thud, thud, thud. I held the rifle waist-high; at this close range there was no need to sight. As I stepped around the point, the drumming stopped. Standing with the hatchet in his hand, Hay blinked excitedly in the sun. At his feet lay the carved wolf’s head, surrounded by wood chips. “If I can cut the head off, it’ll fit under my bunk,” he said.

Maybe it was the dead man, or the long days and sleepless nights, or the blinding beach after the forest gloom. Whatever it was, something in me snapped, and I fired the rifle, pumped and fired again and again. The cove shook with the echoes and the wolf’s head flew to pieces and lay shattered in the sand. I turned the gun on Hay with my finger still on the trigger. Out there, way out there, like out at sea, things change, things can happen. One forgets that anything exists but “out there.” Someone rang the ship’s bell. We didn’t move.

“The tide’s turning,” I said.

I shouldered the hot barrel and went down to the water’s edge to await the skiff’s return.

EVIL’S

H

OLE

D

angerous rocky islands and point are called

no’mas

, Old-Man. In passing…in rough water, the traveler will pray, “Look at me, Old-Man! Let the weather made by you spare me, and, pray protect me that no evil may befall me while I am traveling on this sea.”

—F

RANZ

B

OAS

W

e beat across the sound with all sails flying and a sky the deepest blue. The steep dark slopes closed in as we neared the pass. We were behind schedule for the slack but we couldn’t run the engine, not on a heel, because although it worked fine bucking chop or running swells, when heeled for a time it sputtered, smoked like hell, and died.

Nello steered and trimmed the sails, softly singing a melodic

“Oi Vita, oi vita mia,”

while I, with binoculars, studied the water in the pass, suspiciously smooth with all this wind—the currents beneath much stronger than the blast of air above. Charlie was busy stitching an awning with even more dedication than normal, while Hay sat amidships keeping order in his life by making endless entries in his journal.

No one mentioned the dead man. We were all busy and intent, like schoolboys on an outing. Near the entrance of the pass, with small eddies forming around us, Nello asked if I would take the helm, went below, and came back with the fishing rod and cast off the stern into the current. “Hey, Charlie,” he called out jovially. “I’ll catch you big fish.” He was trying to bring normalcy back to our lives. Charlie knew, and his eyes showed gratitude. The reel whined. “The pail, Charlie! Bring the pail!” Nello reeled slowly but evenly, keeping the pole bent tight, loading the line, not letting the fish throw the hook. Just a few feet from the stern the fish jumped, but Nello whipped the rod so hard it hit the mizzen shroud, and kept the hook in him. Anxious to get the pail under the fish, Charlie threw himself on the stern rail, and might have gone overboard if Nello hadn’t grabbed his belt and pulled him back. To keep him safely there, he placed his bare foot on Charlie’s butt. For a moment he seemed distracted and almost lost the fish, then he reeled in, dipping the tip of the pole in the water to shorten the line and not let him jump again. He maneuvered the shiny salmon under the stern, and Charlie, feeling safe under the foot, blabbered an excited stream of Chinese as he slid farther overboard, his feet churning the air. They got the thrashing fish into the pail. I was watching them so closely I nearly ran us on the rocks.

The first great whirlpool, maybe fifty feet across, surged from below us and swung us toward the shore.

We were late.

This close to land, the wind eased and we sailed upright. Nello went below and turned over the engine shattering the quiet. With its two-cycle throb—the dull explosion, then the long uncanny silence—the Easthope, seemed a tired heart that you could never be sure would ever beat again. With the added push of the engine we surged toward the narrows. The current pulled us in.

Charlie was too busy with the fish to notice, but Hay, sensing a turn in our lives, put away his journal, went below, and came back with his jacket buttoned tight and a pistol in a holster on his belt, as if that would somehow safeguard him from the pass ahead.

Nello came up content with the engine, looked at the languid eddies in the pass, and announced, “Charlie, my little pal, I hope you like dancing, ‘cause we’re about to shimmy and shake. Cappy, give us our orders.”

I sent Hay up to the bow to watch for logs and deadheads, and Charlie to the portside shrouds to watch for rocks.

Eddies now formed everywhere, so there was no way to read the wind in the pass, and with the cold water rising from the sea bottom, and the islands blocking the outflow from the fjords, what the winds would do in there God only knew. On the rocky crags above the tree line, a lodged cloud spewed a misty breath—up high there was wind, but we were here below. The starboard telltale flung itself about, pointed to port, pointed aft, pointed up and down. The port telltale had given up and hung limp. The jib luffed, then collapsed, then back-winded, and slowed us. A deep, hard eddy flung the ketch aside.

“We’re late,” Nello said so softly only I could hear.

“How late?”

“Late late.”

“Maybe we shouldn’t go.”

He looked at the shore speeding by. “We should never have

come

.”

“Well, it’s too late not to come.”

The current and a whirlpool flung us forcefully ahead. He smiled a bitter smile. “And now it’s too late not to go.”

“Play the jib, would you?”

He hurried to the mast, uncleated the jib halyard, and let the jib crumple lifeless to the deck, flattened it to keep the windage down, then stood by with the halyard in hand and studied the currents in the pass. Bits of driftwood and some logs moved about and gulls rode the eddies, waiting for the stream to build and drive the fish to a frenzy. “The portside is with us,” Nello called, and I let her drift closer to shore. A cool gust slapped my face. “Hoist her,” I snapped, and Nello hauled the jib. I called Hay back to take the jib sheet and play it carefully, letting out a few inches, hauling in a few, then throwing it off completely when Nello had to drop the jib again. I had Charlie take the slack sheet and bring it in fast when I yelled, “Charlie, haul.” I uncleated the mainsheet but left it under a horn and played every gust.

We passed the mouth; we were in the pass.

There was little change on the surface—the whirlpools had grown but were still lethargic, the gulls circling as before—but below, felt only as a firm push against the keel or a quick kick of a spoke against my hand, a great force began to move.

“Charlie, haul! Mr. Hay, throw off!”

A whirlpool and the wind hit us all at once, and the boom flew hard and checked to starboard, and the jib swept the deck, tearing the sheet through Hay’s hand.

He yelled out in agony.

“Grab the fish,” I snapped at him. “It’s cold.”

“Rock at ten o’clock!” Nello roared. A mound of white foam swirled up ahead.

“Charlie, throw off!” I had to haul the jib; Hay held the fish before him as if to fend off evil.

The gust held steady. In the middle of the pass the whirlpools swelled enormous—some two boat-lengths across with dark, deep centers, and we weren’t even halfway to turning the corner. Silky, sloping water ran along the shore at maybe four knots, with another silky stream—only a bit higher—running faster right beside it; but in the opposite direction. Suddenly the inner stream reversed and coiled up like a snake.

The logs and gulls were now swept in all directions. Hay wrapped an arm around a shroud. Charlie took no clues from the world, only from Nello’s face. When it showed satisfaction, Charlie beamed; when it showed apprehension, Charlie looked terrified.

Nello hoisted the jib for the third time, muttering

Porca Madonna

and

Dio-cane

, but, upon seeing Charlie’s worried eyes started singing,

“Oi vita, oi vita mia, oi core chistu core, se stato prim’ammore—Whore-log at two o’clock and coming right at us!”

It was a small log, maybe twenty feet long and a couple of feet across, but it was spinning in a whirlpool, so it would hit us like a hammer. We were pushing through with all sails and the Easthope, so there was no way to gain more speed unless we threw the anchors or each other overboard. To port was the shore, and to starboard a steep funnel, so I aimed for the end of the log that spun away from us, hoping just to skim it with the bobstay. I tightened the mainsheet until the blocks quivered. “Hold on!” I cried, and braced myself against the wheel, ready for the blow. But without impact the log vanished. In the long silence of the Easthope compressing, only the whirlpools murmured. Then the Easthope thundered and the log shot from the deep—vertically, right beside the hull—up into the sky. Its tip reached the spreaders, and it teetered, ready to crush us, but instead sank as it had come, back into the sea.

“Let out, Charlie! Let out!”

Hay stared hypnotized. “If that had come up under us—”

“We’d be a three-masted schooner instead of a ketch. Charlie! Haul!”

To port opened a gaping hole that belched the cold breath of the deep and smelled of all things alive and dead on the bottom of the sea. To starboard a wall of water rose and blocked the pass. Six feet tall, it didn’t move; didn’t change. Then, as suddenly as it had come, it sank, leaving a strip of foam that the currents tore to shreds. That was when I first noticed the din. Every whirlpool, every overfall, each stretch of current hissed or roared or gurgled.

“Down the next pass, Cappy!”

The pass seemed to be between a group of rocks and a narrow island, and I spun the wheel. “Let out! Let out!”

We swung. The current from the rocks shouldered us hard sideways. We hung on, all except Nello, who bounded aft, yelling,

“Past

the island! This is all rocks!”

I swung us north again.

Past the island we turned into a narrow cut. The water was smooth, unruffled emerald, but heaving fantastically, as if some giant were shaking an enormous bolt of silk. To the northeast, among some islets, there was no water, only foam. The current flung us viciously ahead. The shores flew by. The sails shook. The tip of the starboard island ended in a bluff, and the emerald stream heaved and swung around it, leaving a deep hole.

We were shot into a bay. There was no foam or heaving, but the entire surface was enormous swirling circles.

“That wasn’t so bad,” I yelled, and Charlie looked back with a frightened smile.

“Nothing to it,” Hay said, brandishing his fish.

“We’re through!” I yelled at Nello beside me.

“Through what?”

“Your killer pass! The narrows!”

He looked at me as if I had lost my mind. “That was the first rapids,” he said.

“Well, they were easy. So why worry?”

“Because we’re later than I thought.”

“For what?”

He didn’t answer; seemed to be counting circles. Then a wave slammed us broadside and spray shot over us. “For that,” he said, pointing beyond the bay, where between black bluffs a dense fog oozed toward us. “Devil’s Hole.”

Beside us a wall of water rose, then spun.

“Hold on!” Nello yelled. His eyes were wild as he yanked the main hatch shut and held on to its grip. “Hold on!”

The world seemed to fall away around the ketch; the stern dropped, then, from behind, the wall of water came. It climbed aboard. The aft deck vanished and the cockpit vanished—only the mizzen mast stuck out of the water—the water that kept climbing up over the cabin.

A

S IF RISING

from a grave, the ketch rose, bit by bit, out of the sea. The cockpit slowly drained. Nello released his grip. We crabbed toward the shore. The waters all around us took up a louder roar.

“There, Cappy!” Nello howled, pointing at a long green river that cut a path among the circles clear across the bay. I steered toward it and caught the edge, and it tried to spit us out, rush away, leave us behind, but I held her in, and we lurched and yawed, at terrific speed, ahead. I heard a roar and spun to look, but the roar was all around us. The great circles swelled, their walls sloped down, and they spun, whirling clockwise, whirling back, whirling all to hell, but the long green stream, like some wondrous locomotion, swept us on. To starboard the sea was a hillock, to port an overfall. We clutched lifelines, grabrails, shrouds, anything we could, looking no less bewildered than if we had awakened on the moon.

It came from the northeast islands through the foam: the black, ungainly tug. Its great, log-pushing teeth chewed through the swirling seas. Her soot-smoke rose, fell, then turned against itself. It had trouble holding course. It seemed headed for Devil’s Hole, but then a whirlpool shot it sideways and it headed straight for us. Someone stuck his head out the pilothouse window, another stood on the bow with his head a glowing red. He held a stubby walking stick, like a gentleman on a stroll. I stared so hard I steered us off the stream.

We fell off the bluff and landed with a thud. “Hold hard!” I roared, and swung the bow into the wall. The wall exploded. Green water buried us. I couldn’t breathe. It hit me that the cabin was being flooded through the cowls. We were sinking. I felt no fear, only disappointment.

Then the darkness lightened and we climbed out into the sun. Water poured down from the booms. The decks were still under, but Nello and Charlie and Hay were there, holding on to whatever they had clutched before.

The tug was much nearer, and coming right at us.

I swung her west.

Nello pulled Charlie to the mainmast, wrapped his arms around it and roared, “Don’t let go! Don’t let go!” He fetched the binoculars and steadied his elbows on the bed-logs, pointed at the tug. Then he handed me the binoculars and said, “Sayami.”

They were ten boat-lengths away, rolling and wallowing, dark and menacing, half buried in the foam. Sayami, his red bandanna glowing in that colorless world, unwrapped his rifle, folded the rag, knelt on it with one knee, and leaned against the coaming for a brace. As I stared at him through the binoculars, he pointed the rifle right between my eyes. But he didn’t fire; we were bobbing, yawing, plunging much too much. Hay stood up with the pistol in his hand, seeming so nervous I thought he’d shoot us all. Sayami just knelt there.

Five boat-lengths.

Hay said in the surprised voice of a child, “He’s going to ram us.”

We stared. Couldn’t believe our eyes.

Three boat-lengths.

A great log shot at us but I couldn’t avoid it; it skimmed the bow, then was at once sucked under. The tug steadied; Sayami aimed.

The tug’s iron teeth headed for amidships where Charlie hid behind the mast, where Nello dove for him, where Hay, undecided, stood with trembling hands, and the tug gave a roar, a belch of smoke, then made its final lunge.

Sayami lowered his rifle. Three shots rang in quick succession, and the world went mad.

As if a volcano had blown below us, the ketch flew into the air and the tug reared, its bow blocking the sky. Then the bow came down with the sound of splintering and grinding, and the air was filled with shards of wood and glass and the stench of gas.

The ketch fell on her side, the masts in the water, the house half sunk, and the tug rammed our keel, trying to plow us to bits before we drowned. Charlie fell. He’d clambered across the cabin top and reached for Nello, but Nello was falling headfirst in the sea. Charlie grabbed air and fell backward off the deck. He went under. The tug hit again and turned us farther over.