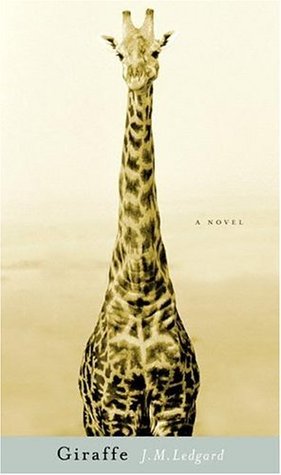

Giraffe

Annotation

An astounding novel based on the true story of the life and mysterious death of the largest herd of giraffes ever held in captivity, in a Czechoslovakian town sleepwalking through communism in the early 1970s.

In 1975, on the eve of May Day, secret police dressed in chemical warfare suits sealed off a zoo in a small Czechoslovakian town and ordered the destruction of the largest captive herd of giraffes in the world. This apparently senseless massacre lies at the heart of J. M. Ledgard's haunting first novel, which recounts the story of the giraffes from their capture in Africa to their deaths far away behind the Iron Curtain. At once vivid and unearthly, Giraffe is an unforgettable story about strangeness, about creatures that are alien and silent, about captivity, and finally about Czechoslovakia, a middling totalitarian state and its population of sleepwalkers.

It is also a story that might never have been told. Ledgard, a foreign correspondent for the

Economist

since 1995, unearthed the long-buried truth behind the deaths of these giraffes while researching his book, spending years following leads throughout the Czech Republic. In prose reminiscent of Italo Calvino and W. G. Sebald, he imbues the story with both a gripping sense of specificity and a profound resonance, limning the ways the giraffes enter the lives of the people around them, the secrecy and fear that permeate 1970s Czechoslovakia, and the quiet ways in which ordinary people become complicit in the crimes committed in their midst.

Economist

since 1995, unearthed the long-buried truth behind the deaths of these giraffes while researching his book, spending years following leads throughout the Czech Republic. In prose reminiscent of Italo Calvino and W. G. Sebald, he imbues the story with both a gripping sense of specificity and a profound resonance, limning the ways the giraffes enter the lives of the people around them, the secrecy and fear that permeate 1970s Czechoslovakia, and the quiet ways in which ordinary people become complicit in the crimes committed in their midst.

- J. M. Ledgard

Giraffe

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

J. M. Ledgard was born on the Shetland Islands, Scotland, in 1968, and educated in England, Scotland, and America. He has been a foreign correspondent for

The Economist

since 1995 and is a contributor to

The Atlantic

. He divides his time between Europe and Africa.

GIRAFFEThe Economist

since 1995 and is a contributor to

The Atlantic

. He divides his time between Europe and Africa.

FOR MARTA ANNA

In MemoriamAlexandr Hackenschmied1907–2004

Sněhurka —Democritus, if he were still on earth, would deride a throng gazing with open mouth at a beast half camel, half leopard.— HORACE

A Giraffe

ST. HUBERT’S DAY

NOVEMBER 3, 1971

I

KICK NOW IN the darkness and see a coming light, molten, veined through the membrane and fluids of the sac, which contains me. I am squeezed toward the light. Let it be said: I enter this world without volition.

KICK NOW IN the darkness and see a coming light, molten, veined through the membrane and fluids of the sac, which contains me. I am squeezed toward the light. Let it be said: I enter this world without volition.

My hooves come first, then my nose, then the whole of my head. I hang halfway out. I swing. I fall. I am found, I am found at this moment, and my coming into being is a head-over-hooves tumble from weightlessness to weight and from the drowning, which has no memory, to what has breath and is yet to be.

It is white-hot out here, thin; it sears. The falling takes the longest time. The first thing I see is my own form, my hooves impossibly far away, slicked with fluid, and my mazed hide, bloodied, flickering in the haze, burning, as though I am not passing from my mother to the ground, but from the constellation Camelopardalis into the Earth’s atmosphere.

The ground comes to me from upside down, a flopping view, flopping with my neck. I see a blue-and-cream swallow flying close and away up onto an ash-colored grassland, where forms of other animals and trees are pegged to the soil, not falling into the azure sky below. I hit the ground headfirst, with a thud. Dust rises about me and settles. I lie quite still, among gathering ants, taking the measure of the air and of gravity. I blink back the light of the sun. I feel my lungs swelling. My heart beats on its own account, for me alone. Such a volume of blood passes through my chambers, rises, and rises again, and sinks, circulating within me, creating a buoyancy that will keep me upright for all my living days.

My mother nudges me with a hoof and now with her nose. She licks membrane from my hide in a thoroughgoing manner. I do not stir. I remain motionless in the dust until the shadow of a cloud settles above me and comforts me; I am without understanding and remember nothing of constellations but only that it was darker and thicker where I came from. I slowly lift my neck. I kick out my legs. I try to stand. Several times I climb up and several times I fall back down, so there is a question about my form: How can I be upraised on such slender legs? Now I make it. I quiver here, beside my mother. Instincts and customs of the herd enter me, unbidden. I see the order of my captivity, my searching up, gravity pulling me down, and the resultant journeys across. The sounds of this world, which came at first to me as single and unbroken, break now into songs of the earth, of termites, vultures, armored beasts wallowing, and of my own breath. I run a little, from one cloud shadow to another and back again to my mother, as on stilts.

I know I will grow fast now, as grass after rain, and that the form of my growing shall be upward. This is as it should be, as it was ordained since my earliest embryonic stage, for I am a giraffe and everything about my body is for stretching up. I am a giraffe, I am about that space a little above the blade, and my bodily intent is to be elevated above all other living things, in defiance of gravity.

Sněhurka — APRIL 7, 1973I

HAVE GROWN INTO the finest young cow in my herd. I move confidently down cuts in the hills of red stone that bound the ash-colored grassland and emerge at other places, among various striped zebras. Most of the giraffes born with me have died of sickness or been killed by predators in their infancy. No lioness has come for me. I am alive under these acacia trees. I browse on my hind legs now, in the upper branches, where bull giraffes most often have claim. I am aware: I see the green metal flying toward me in this white light. I try to move out of its path; I know it is a tranquilizer dart. It deeply pierces my rump. A band of Czechoslovakians resolves out of the thorn trees. I bleat once at them — the first audible sound I have ever made. I run in one direction; my herd runs in another. How I run from these Czechoslovakians! My legs extend, my mane catches in the wind. Faster and faster I go; I reach a full gallop, swifter than any horse. It is no use. The Czechoslovakians keep pace behind me in tan-colored trucks that bounce over dry streambeds and rip through insect trails.

HAVE GROWN INTO the finest young cow in my herd. I move confidently down cuts in the hills of red stone that bound the ash-colored grassland and emerge at other places, among various striped zebras. Most of the giraffes born with me have died of sickness or been killed by predators in their infancy. No lioness has come for me. I am alive under these acacia trees. I browse on my hind legs now, in the upper branches, where bull giraffes most often have claim. I am aware: I see the green metal flying toward me in this white light. I try to move out of its path; I know it is a tranquilizer dart. It deeply pierces my rump. A band of Czechoslovakians resolves out of the thorn trees. I bleat once at them — the first audible sound I have ever made. I run in one direction; my herd runs in another. How I run from these Czechoslovakians! My legs extend, my mane catches in the wind. Faster and faster I go; I reach a full gallop, swifter than any horse. It is no use. The Czechoslovakians keep pace behind me in tan-colored trucks that bounce over dry streambeds and rip through insect trails.

Chemicals rise within me. I slow. My eyes open into hemispheres of panic and then dull from the etorphine. My head falls back, my muzzle rises, my ears flatten. I cannot go on. I have no breath; all the air in my trachea is dead. The trucks circle. Around and around they go, revving, braking, drawing close. I move toward a watering hole, thinking to drink. A Czechoslovakian in a safari hat jumps out of one of the trucks. He makes a hand signal. Two African men rush forward and steal in under me. They draw a short rope around the upper part of my forelegs and my chest. A few Czechoslovakians come close now and sling a noose about my neck. They all of them pull smoothly at the ropes. I reel. I collapse. I feel these men around me, upon me, impossibly above me. I try to kick out at them, to catch them with a hoof, but there is nothing in me, there is no control. The Czechoslovakian in the safari hat kneels down beside me. I feel his hands around my throat, searching for my jugular vein. He finds it. He takes a long needle and drives it through my hide into the vein and injects me with the antidote diprenorphine. I am blindfolded. My ears are packed with cotton wool and muslin. I feel myself hauled upright and walked to one of the trucks.

I am tied to hot planking and driven now on the back of this truck in a silence and blindness that is my own, that is not of the womb, but is instead immediate, fearful, buffeting, hot with the midday sun. I am unbound and unmasked at a makeshift camp under the red hills. The Czechoslovakians stop and stare up at me. They examine me and give me the name

Sněhurka,

or Snow White, because of the unusual whiteness of my underbelly and legs, which they say reminds them of the snows of Kilimanjaro. From this point on, for as long as I live, the voices of men will call after me, “Sněhurka!” They will call my name, and I will recognize the sound, as I have long ago learned to distinguish the sound of one insect from another.

Sněhurka,

or Snow White, because of the unusual whiteness of my underbelly and legs, which they say reminds them of the snows of Kilimanjaro. From this point on, for as long as I live, the voices of men will call after me, “Sněhurka!” They will call my name, and I will recognize the sound, as I have long ago learned to distinguish the sound of one insect from another.

There are many other captured giraffes in the camp. We are not divided between our subspecies. I am fenced in with Rothschild and Masai giraffes as well as other reticulated giraffes. We are not so separate. Our height and gaits are similar, our horns are the same iron color. Only the patterns of our hides are distinct: the Rothschild blotched, the Masai drawn in fig leaves of Adam, the reticulated, as mine, in a fine lattice of white. We might mingle and breed, although this sometimes produces blank offspring, free of any marking.

There is one young Rothschild bull placed in a pen by himself. He rushes about in fits. He snorts. He draws back his neck and shoulders in a bow and bares his yellow teeth like a wild ass. He keeps himself drawn tight until this moment, when the Czechoslovakians shrug, open the fencing, and set him free. I watch him buck and skid out past the tents in the camp onto the grassland, disappearing quickly out of sight.

“Look at his neck,” one of the Czechoslovakians says. “See how it rolls forward and back with each stride, like the mast of a sailing ship in a heavy sea.”

I STAND LOOSE AND SILENT near the fence. I am aware of the barefoot African boys who feed me branches and fruit, moving by me in the darkness. They carry pails of water and walk with their heads down, watching for sharp stones. I make out their patterns, the contrast between the pink soles of their feet and the dusty black of their calves.

Czechoslovakians move between us, making observations, taking measurements.

“There is socialism in our method,” I hear them say. “Capitalists capture one or two giraffes, while we take an entire herd; because our intention is political, to issue forth a new subspecies.”

Other Czechoslovakians are gathered around the camp-fire. Their white faces are open to laughter and to drafts of clear

slivovice,

or plum brandy. Their shadows fall giant-sized and gaping-mouthed upon me and upon the other giraffes, who are also silent and sleepless, who also step lightly through these shadows, watching the lanterns the guards swing at the edge of the camp to scare away hyenas. We watch through the night how these guards set down their rifles and drop on their haunches to contemplate the moon or to smoke a Czechoslovakian cigarette.

slivovice,

or plum brandy. Their shadows fall giant-sized and gaping-mouthed upon me and upon the other giraffes, who are also silent and sleepless, who also step lightly through these shadows, watching the lanterns the guards swing at the edge of the camp to scare away hyenas. We watch through the night how these guards set down their rifles and drop on their haunches to contemplate the moon or to smoke a Czechoslovakian cigarette.

A CZECHOSOLVAKIAN STOPS before me now.

“Sněhurka is strong enough for transport,” he says to the others. “She will not die at sea.”

“True enough,” one of the others says. “And see how calm she is. Calm enough certainly to survive in our zoo.”

I have no answer to this; I do not even bleat, and so am condemned to further captivity, not only of time and gravity, but in the passage across also. If only I had stood against the Czechoslovakians as the young bull giraffe did, baring my teeth, or stumbled deflated about the back of the enclosure, then perhaps the fence would be opened to me as it is now to the weak and nervous Masai giraffes. They are sorted and set free. They do not buck and skid off as the young bull did, but stand in the camp looking back at the rest of us, the strong and stately giraffes, wondering at our confinement, where food comes easily, without reaching up. Only after shots are fired over their heads do they move off.

THE CZECHOSLOVAKIANS ARE closing down the camp. I am roped again and placed on a truck. I stand tethered here, looking deep into this cool dawn, waiting for them to come with the blindfold. I see a line of other giraffes similarly waiting. I see gray mist shrouding the caps of the red hills; the rains will be here soon. I see a single star low and bright over the grassland. I see the Masai giraffes turning lonely circles on the sunlit horizon, seemingly in flames.

Other books

Doppelgänger by Sean Munger

El enigma de la Atlántida by Charles Brokaw

Shards by Allison Moore

EllRay Jakes is a Rock Star! by Sally Warner

Wayward Winds by Michael Phillips

1973 - Have a Change of Scene by James Hadley Chase

Royal Bastard by Avery Wilde

Steady Now Doctor by Robert Clifford

The Box by Unknown

Jennifer Haigh by Condition