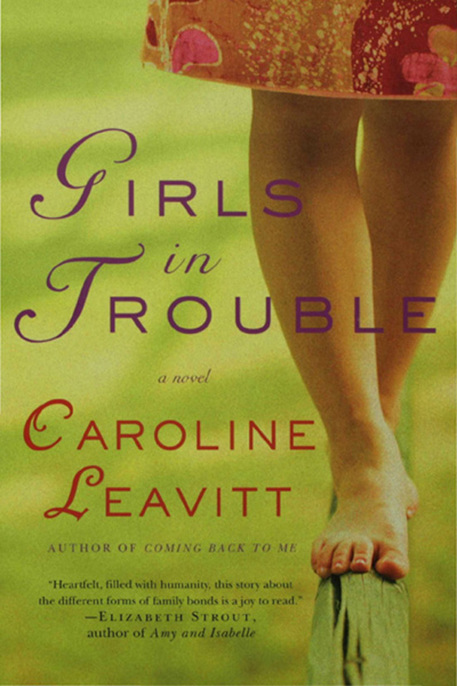

Girls in Trouble

Authors: Caroline Leavitt

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #Family Life, #Contemporary Women

girls

in

trouble

PREVIOUS

BOOKS BY

Caroline

Leavitt

Coming Back to Me

Living Other Lives

Into Thin Air

Family

Jealousies

Lifelines

Meeting Rozzy Halfway

GIRLS IN TROUBLE

. Copyright © 2004 by Caroline Leavitt. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Leavitt, Caroline.

Girls in trouble / Caroline Leavitt.

p. cm.

Summary: Abandoned by her boyfriend and at odds with her parents for choosing open adoption, Sara, a sixteen-year-old honor student, is sustained by her relationship with her daughter’s adoptive parents until they become threatened by her increasing obsession with the baby and make a decision that has devastating consequences for everyone.

ISBN 0-312-27122-0 (he)

ISBN 0-312-33973-9 (pbk)

EAN 978-0312-33973-9

[1. Teenage mothers—Fiction. 2. Mothers and daughters—Fiction. 3. Adoption—Fiction. 4. Pregnancy—Fiction.] I.Title.

PZ7.L4643G1 2003

[Fie]—dc21

200300912

First St. Martin’s Griffin Edition: April 2005

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Jeff

and Max

with all my love

I

must have been unbelievably good in a past life to have the sublimely wonderful, warm, smart, and funny Gail Hochman as my agent and friend in this one. Never was any writer luckier, more blessed—or more thrilled. Thank you, thank you, thank you, Gail. Huge thanks, too, to the absolutely wonderful Joanne Brownstein.

A

multitude of deepest thanks goes to my terrific editor, Jennifer Weis, and her assistant, Robin Carter, at St. Martin’s, and to all the stellar souls at St. Martin’s.

F

or reading, editorial advice, and support way beyond the call, huge thanks to Jeff Tamarkin, Jo Fisher, Jo-ann Mapson, Liza Nelson, Linda Corcoran, Jennifer Robinson, Mickey Pearlman, and Jane Praeger. Very, very special thanks to Katharine Weber, Rochelle Jewell Shapiro, and M. J. Rose.

F

or help in getting my facts straight, huge thanks to Elaine Abdow, the adoption social worker at Catholic Social Services of Fall River, Massachusetts; and to Bill Bentzen, Peter J. Salzano, Lindy Judge, Jim Lambros, and Dr. Joseph Towbin.

A

nd for many, many kindnesses, thank you to Clea Simon, Jane Bernstein, Janet Falon, Victoria Zackheim, Gayle Brandeis, Mary Morris, Karen Templer and the wonderful denizens of

Readerville.com

; my mother, Helen Leavitt; my sister, Ruth Rogers; and Jonathan and Hillary.

A

nd, of course, this book—as does everything in my life—owes endless thanks to my funny, loving partner-in-crime, my writer-across-the-hall, my most beloved Jeff. And to our miracle of miracles, Max.

girls

in

trouble

one

S

ara’s pains are coming ten minutes apart now. Every time one comes, she jolts herself against the side of the car, trying to disappear. Everything outside is whizzing past her from the car window because Jack, her father, is speeding, something she’s never seen him do before. Sara grips the armrest, her knuckles white. She presses her back against the seat and digs her feet into the floor, as if any moment she will fly from the car.

Stop

, she wants to say.

Slow down. Stop

. But she can’t form the words, can’t make her mouth work properly. Can’t do anything except wait in terror for the next pain. Jack hunches over the wheel, beeping his horn though there isn’t much traffic. His face is reflected in the rearview mirror, but he doesn’t look at her. Instead, he can’t seem to keep himself from looking at Abby, Sara’s mother, who is sitting in the back with Sara. His face is unreadable. He keeps pushing back his hair, thick and brown, dimmed with grey. He punches the radio dial from station to station, smearing the sound.

“Jack, for God’s sake,” says Abby. “Just pick a station.” Abby hands Sara a hard lemon candy to suck on. She rubs Sara’s shoulders, helps her wedge the pink rubber ball into the small of her back to press against the pain. The dress Sara’s been living in for months, a blue denim that’s two sizes bigger than the one she used to wear, soft from many washings, is soaked with sweat, pasted to her. Her hair snarls to her shoulders, the

same rust red as her mother’s short, styled cut, only hers is damp, frizzy with curls. No matter how frosty the car gets, Sara can’t stop sweating.

“Nineteen eighty-seven and it’s the worst heat wave in Boston in fifty years!” the radio announcer says. He keeps saying his name, which is Wild Bill, and every time he says it, he laughs, and the laughter gets under Sara’s skin, crawling like some sort of insect. “We’ve never seen a July like this one!” He’s got a crackling, gleeful voice that pops and snaps as if it were carbonated. “Keep inside, keep cool, keep tuned in. There’s a health hazard warning for elderly and pregnant women.” Sara feels a small shock of recognition, as if the announcer were talking directly to her, but Abby keeps rubbing her bare shoulders as if she hasn’t heard anything, and Jack purposefully zips into another lane. Abby’s face is coated with sweat. Perspiration beads on Jack’s neck. “Two people have died already,” Wild Bill says and Sara thinks, amazed,

I’m dying, too

. He talks about drought and blackouts and crime waves because people are going crazy from the heat. No one can be counted on to behave reasonably. An elderly woman was found by a neighbor, panting on her floor by her open refrigerator. A white teacup poodle has nearly suffocated in a car left in a parking lot, but was revived when his desperate owner gave him mouth to mouth. “Even Wild Bill isn’t wild enough to do

thatl”

Wild Bill says.

Sara swears his voice is growing louder and bigger, crowding out all the room in the car, all the air, and she can’t stand listening to it another moment and she’s about to say so when another pain grabs at her and instead she cries out.

“Oh, honey,” Abby says, turning to her, trying to push back Sara’s hair, which is so wet now it’s strings. “It’s almost over. Almost over now.”

Pain crunches down on Sara. “No,” she gasps. “No, it’s not.”

“Soon,” her mother promises. “Soon.” Her mother’s hands float over her.

Jack punches in another station. A long, itchy slide of jazz comes on, making Sara flinch. “Here’s the turn,” Jack says. His voice is low and determined.

Jack has taken a day off. He’s an accountant and his cell phone sits beside him on the seat, and the only reason he’s brought it is in case they need to call the doctor, or the car breaks down, or any number of disasters

that surely couldn’t be any worse for everybody than this one. Abby’s a dental hygienist in Belmont and she’s taking off a week, something unheard of for her. Usually she’s so concerned with everyone else’s teeth, she neglects her own when she comes home, but now it’s different. “Everyone can take care of their own pearly whites for a change,” she says. Every time Abby looks at Sara, Abby changes into something Sara’s stopped recognizing. Abby’s beauty leaves her. Her eyes, usually blue and soft as felt, become distant. Her mouth takes on a funny slope. And sometimes, when Sara least expects it, Abby’s face saddens with regret.

Sara has a lawyer Abby had found, a woman at a Newton adoption agency named Margaret Robins. Every time Margaret talks to Sara, she asks pointedly, “Do you understand?” Abby asks that same question, too, but Jack won’t discuss anything with Sara anymore, not even a thing as simple as how he feels. Instead, he’s gone mute.

The car bumps, like a reproach from her father, and Sara winces at the flash of pain. Abby rubs her back. “It’ll be over soon. Think of your future. Think of school.”

Sara is an honor student. Sixteen years old and her guidance counselor already is pushing early admission to Columbia. To Harvard. She loves to say Sara can write her own ticket, which is something Abby repeats like a mantra. “You’re smart,” she says, but what Sara hears is that Sara may be smart, but she isn’t smart enough not to be pregnant.

Sara used to have her life planned. She used to want to be a doctor—a psychiatrist—a decision she made the first time she picked up an issue of

Psychology Today

and couldn’t stop reading it. When she was twelve, Abby gave her her own subscription, which Sara devoured, saving all her issues on a special shelf, highlighting the articles that caught and held her interest. Abby loved to leaf through the issues herself. “Nothing wrong with improving my mind, too,” she told Sara. “It’s terrific you know what you want now. A girl has to know what she wants early and stick to it, or she can get robbed of her life.”

“Robbed?” Sara had looked up from the article she was reading, “Body Talk!” She glanced at herself in the mirror to try and decipher her own string-bean build.

“Oh, I’m just being melodramatic,” Abby said, waving her hand, but

Sara studied her mother. Abby was folding towels, her prim white lab coat over a shocking-pink dress with a ruffled hem. Her back was hunched, her mouth tense. Abby used to want to be a dentist; she had finished a whole year of dental school when she met Jack. She had shown Sara the photograph of her in school, standing in front of a big brick building, her arms loaded with books, her red hair flying, her face flushed with joy. “Why’d you give that up?” Sara had asked her, and Abby had continued folding. “Easier,” she said. “I met your father and got married, then you came along, and who else was going to stay home and raise you? Your father didn’t trust anyone else but me.”

“You could go back,” Sara said, and Abby shrugged. “Now? How could I do that?” Sara looked at Abby with interest. “Why are you looking at me like that?” Abby asked.

Sara held up the magazine. “I was just trying to read your body language.

“I’ll translate for you,” Abby said, rubbing at her temple. “I’m fluent in headache.”

Sara no longer knows what her future holds.

Psychology Today

comes in the mail, the cover so glossy it reflects light back at her, and she doesn’t even open it to see what’s in the table of contents, because, really, what does it have to do with her now?

Shortly before her stomach started to swell, she went to a fortuneteller, one of those five-dollar places with a turbaned woman on a ratty couch. All Sara wanted was to be told good news. She walked inside and sat on the edge of the couch and the woman gave her a cup of tea that tasted like dishwater and then dumped the cup upside down on a plate. “Ah,” she said, poking a finger into the leaves. “Seventy dollars and misfortune is gone.”

“I don’t have seventy dollars,” Sara said and the woman shrugged.

“Then you have misfortune,” she said, but Sara didn’t need a fortuneteller to tell her that.

“Grab on to me,” Abby says now, offering her arm. Sara wrenches away. If she touches her mother’s arm, she’s afraid she’ll beg for help, she’ll scream, she’ll do whatever it is Abby wants if Abby will just take this pain from her. She looks at the locks on the car, the windows sealed

shut, the way she’s so trapped. There’s no air. She can’t breathe. Surely, she’s dying. She concentrates on the slow

whomp, whomp, whomp

, inside of her, like some strange animal coming closer, biding its time to strike. It’s the most astonishing feeling she’s ever had. She suddenly thinks of this movie she once saw called

It’s Alive!

Babies born with teeth, vicious killers who devoured their parents.

Whomp

. Another pain and Sara starts feeling more afraid. She starts thinking,

What was that? What have I done? What’s going to happen?

She’s been so stupid about her own body. She kept telling herself,

If I don’t think about it, it won’t exist

.

A contraction buckles Sara over, banding her stomach with fire. Panicked, Sara grips the seat. “Mom,” she says uneasily. “Mommy—”

If she hadn’t bitten her fingernails, she would have dug them into the vinyl. “Pant,” Abby orders, sucking in her own breath, but Sara can’t. All she can do is ride the pain, hold on fast, and pray it will end. Sara had never actually believed she would give birth, and now there’s no escape. “First births can take eighteen hours,” one doctor has told her, and Sara had thought he was just trying to scare her, to punish her, even. Another pain, deeper this time.

Whomp

. She winces and Abby grips her hand. Sara presses her hands along her back and the pain stops a little. Or maybe it just tightens, like a steel garrote.

Jack skids, flinging Sara against the side of the car. “Everyone all right?” he asks.

“Jack, for God’s sake!” Abby says. And then something happens, a wave of pain shoots down Sara’s back. It has a life of its own, an unstoppable force. She gasps and she’s suddenly drenched from her waist on down. Something is pouring out of her, uncontrollably, like pee, like bathwater. The floor of the car is suddenly soaked. Sara locks eyes with Abby. “It’s okay,” Abby says, taking her hand, speaking calmly, but Sara can feel how her mother’s hand trembles. She feels the sound of the road deep within her skin. She hears the whisper of the other drivers, flowing through her like river water. Her grip tightens. She makes a sound, harsh, scraped from her throat, and Abby stiffens. “Jack, can you please just go

fast,”

Abby says. Jack’s hands tighten on the wheel.