Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the Making of Meaning (12 page)

Read Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the Making of Meaning Online

Authors: Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Tags: #Self-Help

W

E HAVE SEEN HOW PEOPLE DESCRIBE

the common characteristics of optimal experience: a sense that one’s skills are adequate to cope with the challenges at hand, in a goal-directed, rule-bound action system that provides clear clues as to how well one is performing. Concentration is so intense that there is no attention left over to think about anything irrelevant, or to worry about problems. Self-consciousness disappears, and the sense of time becomes distorted. An activity that produces such experiences is so gratifying that people are willing to do it for its own sake, with little concern for what they will get out of it, even when it is difficult, or dangerous.

But how do such experiences happen? Occasionally flow may occur by chance, because of a fortunate coincidence of external and internal conditions. For instance, friends may be having dinner together, and someone brings up a topic that involves everyone in the conversation. One by one they begin to make jokes and tell stories, and pretty soon all are having fun and feeling good about one another. While such events may happen spontaneously, it is much more likely that flow will result either from a structured activity, or from an individual’s ability to make flow occur, or both.

Why is playing a game enjoyable, while the things we have to do every day—like working or sitting at home—are often so boring? And why is it that one person will experience joy even in a concentration camp, while another gets the blahs while vacationing at a fancy resort? Answering these questions will make it easier to understand how experience can be shaped to improve the quality of life. This chapter will explore those particular activities that are likely to produce optimal experiences, and the personal traits that help people achieve flow easily.

When describing optimal experience in this book, we have given as examples such activities as making music, rock climbing, dancing, sailing, chess, and so forth. What makes these activities conducive to flow is that they were

designed

to make optimal experience easier to achieve. They have rules that require the learning of skills, they set up goals, they provide feedback, they make control possible. They facilitate concentration and involvement by making the activity as distinct as possible from the so-called “paramount reality” of everyday existence. For example, in each sport participants dress up in eye-catching uniforms and enter special enclaves that set them apart temporarily from ordinary mortals. For the duration of the event, players and spectators cease to act in terms of common sense, and concentrate instead on the peculiar reality of the game.

Such

flow activities

have as their primary function the provision of enjoyable experiences. Play, art, pageantry, ritual, and sports are some examples. Because of the way they are constructed, they help participants and spectators achieve an ordered state of mind that is highly enjoyable.

Roger Caillois, the French psychological anthropologist, has divided the world’s games (using that word in its broadest sense to include every form of pleasurable activity) into four broad classes, depending on the kind of experiences they provide.

Agon

includes games that have competition as their main feature, such as most sports and athletic events;

alea

is the class that includes all games of chance, from dice to bingo;

ilinx

, or vertigo, is the name he gives to activities that alter consciousness by scrambling ordinary perception, such as riding a merry-go-round or skydiving; and

mimicry

is the group of activities in which alternative realities are created, such as dance, theater, and the arts in general.

Using this scheme, it can be said that games offer opportunities to go beyond the boundaries of ordinary experience in four different ways. In agonistic games, the participant must stretch her skills to meet the challenge provided by the skills of the opponents. The roots of the word “compete” are the Latin

con petire

, which meant “to seek together.” What each person seeks is to actualize her potential, and this task is made easier when others force us to do our best. Of course, competition improves experience only as long as attention is focused primarily on the activity itself. If extrinsic goals—such as beating the opponent, wanting to impress an audience, or obtaining a big professional contract—are what one is concerned about, then competition is likely to become a distraction, rather than an incentive to focus consciousness on what is happening.

Aleatory games are enjoyable because they give the illusion of controlling the inscrutable future. The Plains Indians shuffled the marked rib bones of buffaloes to predict the outcome of the next hunt, the Chinese interpreted the pattern in which sticks fell, and the Ashanti of East Africa read the future in the way their sacrificed chickens died. Divination is a universal feature of culture, an attempt to break out of the constraints of the present and get a glimpse of what is going to happen. Games of chance draw on the same need. The buffalo ribs become dice, the sticks of the I Ching become playing cards, and the ritual of divination becomes gambling—a secular activity in which people try to outsmart each other or try to outguess fate.

Vertigo is the most direct way to alter consciousness. Small children love to turn around in circles until they are dizzy; the whirling dervishes in the Middle East go into states of ecstasy through the same means. Any activity that transforms the way we perceive reality is enjoyable, a fact that accounts for the attraction of “consciousness-expanding” drugs of all sorts, from magic mushrooms to alcohol to the current Pandora’s box of hallucinogenic chemicals. But consciousness cannot be expanded; all we can do is shuffle its content, which gives us the impression of having broadened it somehow. The price of most artificially induced alterations, however, is that we lose control over that very consciousness we were supposed to expand.

Mimicry makes us feel as though we are more than what we actually are through fantasy, pretense, and disguise. Our ancestors, as they danced wearing the masks of their gods, felt a sense of powerful identification with the forces that ruled the universe. By dressing like a deer, the Yaqui Indian dancer felt at one with the spirit of the animal he impersonated. The singer who blends her voice in the harmony of a choir finds chills running down her spine as she feels at one with the beautiful sound she helps create. The little girl playing with her doll and her brother pretending to be a cowboy also stretch the limits of their ordinary experience, so that they become, temporarily, someone different and more powerful—as well as learn the gender-typed adult roles of their society.

In our studies, we found that every flow activity, whether it involved competition, chance, or any other dimension of experience, had this in common: It provided a sense of discovery, a creative feeling of transporting the person into a new reality. It pushed the person to higher levels of performance, and led to previously undreamed-of states of consciousness. In short, it transformed the self by making it more complex. In this growth of the self lies the key to flow activities.

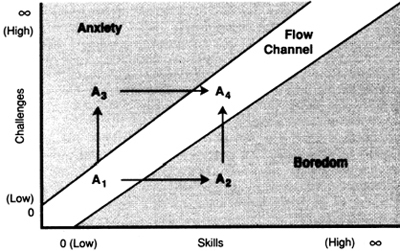

Why the complexity of consciousness increases as a result of flow experiences

A simple diagram might help explain why this should be the case. Let us assume that the figure below represents a specific activity—for example, the game of tennis. The two theoretically most important dimensions of the experience, challenges and skills, are represented on the two axes of the diagram. The letter A represents Alex, a boy who is learning to play tennis. The diagram shows Alex at four different points in time. When he first starts playing (A

1

), Alex has practically no skills, and the only challenge he faces is hitting the ball over the net. This is not a very difficult feat, but Alex is likely to enjoy it because the difficulty is just right for his rudimentary skills. So at this point he will probably be in flow. But he cannot stay there long. After a while, if he keeps practicing, his skills are bound to improve, and then he will grow bored just batting the ball over the net (A

2

). Or it might happen that he meets a more practiced opponent, in which case he will realize that there are much harder challenges for him than just lobbing the ball—at that point, he will feel some anxiety (A

3

) concerning his poor performance.

Neither boredom nor anxiety are positive experiences, so Alex will be motivated to return to the flow state. How is he to do it? Glancing again at the diagram, we see that if he is bored (A

2

) and wishes to be in flow again, Alex has essentially only one choice: to increase the challenges he is facing. (He also has a second choice, which is to give up tennis altogether—in which case A would simply disappear from the diagram.) By setting himself a new and more difficult goal that matches his skills—for instance, to beat an opponent just a little more advanced than he is—Alex would be back in flow (A

4

).

If Alex is anxious (A

3

), the way back to flow requires that he increase his skills. Theoretically he could also reduce the challenges he is facing, and thus return to flow where he started (in A

1

), but in practice it is difficult to ignore challenges once one is aware that they exist.

The diagram shows that both A

1

and A

4

represent situations in which Alex is in flow. Although both are equally enjoyable, the two states are quite different in that A

4

is a more

complex

experience than A

1

. It is more complex because it involves greater challenges, and demands greater skills from the player.

But A

4

, although complex and enjoyable, does not represent a stable situation, either. As Alex keeps playing, either he will become bored by the stale opportunities he finds at that level, or he will become anxious and frustrated by his relatively low ability. So the motivation to enjoy himself again will push him to get back into the flow channel, but now at a level of complexity even

higher

than A

4

.

It is this dynamic feature that explains why flow activities lead to growth and discovery. One cannot enjoy doing the same thing at the same level for long. We grow either bored or frustrated; and then the desire to enjoy ourselves again pushes us to stretch our skills, or to discover new opportunities for using them.

It is important, however, not to fall into the mechanistic fallacy and expect that, just because a person is objectively involved in a flow activity, she will necessarily have the appropriate experience. It is not only the “real” challenges presented by the situation that count, but those that the person is aware of. It is not skills we actually have that determine how we feel, but the ones we think we have. One person may respond to the challenge of a mountain peak but remain indifferent to the opportunity to learn to play a piece of music; the next person may jump at the chance to learn the music and ignore the mountain. How we feel at any given moment of a flow activity is strongly influenced by the objective conditions; but consciousness is still free to follow its own assessment of the case. The rules of games are intended to direct psychic energy in patterns that are enjoyable, but whether they do so or not is ultimately up to us. A professional athlete might be “playing” football without any of the elements of flow being present: he might be bored, self-conscious, concerned about the size of his contract rather than the game. And the opposite is even more likely—that a person will deeply enjoy activities that were intended for other purposes. To many people activities like working or raising children provide more flow than playing a game or painting a picture, because these individuals have learned to perceive opportunities in such mundane tasks that others do not see.

During the course of human evolution, every culture has developed activities designed primarily to improve the quality of experience. Even the least technologically advanced societies have some form of art, music, dance, and a variety of games that children and adults play. There are natives of New Guinea who spend more time looking in the jungle for the colorful feathers they use for decoration in their ritual dances than they spend looking for food. And this is by no means a rare example: art, play, and ritual probably occupy more time and energy in most cultures than work.

While these activities may serve other purposes as well, the fact that they provide enjoyment is the main reason they have survived. Humans began decorating caves at least thirty thousand years ago. These paintings surely had religious and practical significance. However, it is likely that the major raison d’être of art was the same in the Paleolithic era as it is now—namely, it was a source of flow for the painter and for the viewer.

In fact, flow and religion have been intimately connected from earliest times. Many of the optimal experiences of mankind have taken place in the context of religious rituals. Not only art but drama, music, and dance had their origins in what we now would call “religious” settings; that is, activities aimed at connecting people with supernatural powers and entities. The same is true of games. One of the earliest ball games, a form of basketball played by the Maya, was part of their religious celebrations, and so were the original Olympic games. This connection is not surprising, because what we call religion is actually the oldest and most ambitious attempt to create order in consciousness. It therefore makes sense that religious rituals would be a profound source of enjoyment.

In modern times art, play, and life in general have lost their supernatural moorings. The cosmic order that in the past helped interpret and give meaning to human history has broken down into disconnected fragments. Many ideologies are now competing to provide the best explanation for the way we behave: the law of supply and demand and the “invisible hand” regulating the free market seek to account for our rational economic choices; the law of class conflict that underlies historical materialism tries to explain our irrational political actions; the genetic competition on which sociobiology is based would explain why we help some people and exterminate others; behaviorism’s law of effect offers to explain how we learn to repeat pleasurable acts, even when we are not aware of them. These are some of the modern “religions” rooted in the social sciences. None of them—with the partial exception of historical materialism, itself a dwindling creed—commands great popular support, and none has inspired the aesthetic visions or enjoyable rituals that previous models of cosmic order had spawned.