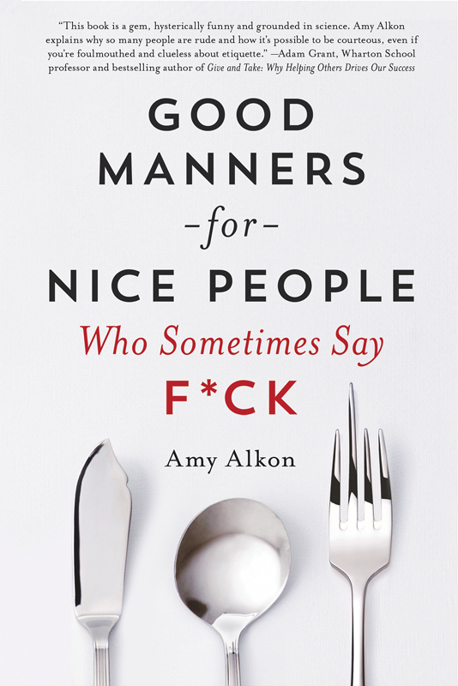

Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck

Read Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck Online

Authors: Amy Alkon

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

To Gregg Sutter, whom I can always count on—to do the right thing, to make me laugh, and to make me dinner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing a book is both a solo undertaking and a team affair, and in the latter department, I’ve really lucked out.

I’m exceptionally grateful to my editor at St. Martin’s, Michael Flamini, for his wisdom, taste, and humor, and for believing in me, and to my wonderful agents and ever-wise and kind guides, Cameron McClure and Ken Sherman.

Danielle Fiorella at St. Martin’s gave me the sort of cover that authors usually only dream of, and everyone at St. Martin’s has been behind me and this book in a way I am wildly grateful for.

Deep thanks go to: my boyfriend, Gregg Sutter, for all his love and support and for seeing that I always had something to eat besides the aging stack of Costco hamburgers in my freezer; Stef Willen, a talented writer who edited my rough manuscript and had the integrity to fight with me when she knew I was wrong; Etel Sverdlov, who gave me really important and helpful comments in the rough stages; Christina Nihira (“The Velvet Whip”) for her loyalty, wisdom, and kindness; copy editor David Yontz, the grammar ninja on this book and my syndicated column, who spots errors few others would and is incredibly good-natured when I (frequently) resort to this Elmore Leonard-ism: “When proper usage gets in the way, it may have to go.”

I so appreciate the generosity of those who read and gave me notes on my entire manuscript—anthropologist A.J. Figueredo, bioengineer Barbara Oakley, and biographer David Rensin. Thank you also to economist Tamas David-Barrett, who read several chapters that relate to his and Robin Dunbar’s research. And thanks to friends and family who read and commented on various chapters: Debbie Levin, Erika, Ruth Waytz, Christina Nihira, DB Cooper, and my incisive, wise, and wacky sister, Caroline Belli.

I’m also extremely grateful to the members of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, the NorthEastern Evolutionary Psychology Society, and the Applied Evolutionary Psychology Society, who have, for over a decade, been warm, welcoming, and helpful to me in my mission to turn their research into “science news people can use.”

This book was helped into being in part by the generosity, friendship, and support of a number of people in my life: Kate Coe; Sandra Tsing-Loh; Patt Morrison; John Phillips; Matthew Pirnazar; Marjorie Braman; Dee Dee DeBartlo; Andrea Grossman; free speech defender Marc J. Randazza; economist Robert H. Frank; Jackie Danicki; my blog commenter regulars; Maret Orliss, Ann Binney, and all the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books peeps; my New York family, the Housers; my Paris family, Mark, Chantal, Pierre, and Emily; and Linda and Linda at 18th Street Coffeehouse, who are wonderful to writers and ban cellboors.

And, finally, thank you to all of you readers who have bought this book and

I See Rude People

, and who do your part to make the world a less rude and more warm, welcoming, and amusing place for all of us.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Acknowledgments

1.

I Don’t Care Where You Put the Fork

(as long as you don’t stab anybody in the eye with it)

2.

We’re Rude Because We Live in Societies Too Big for Our Brains

The science of stopping the rude

3.

Communicating

4.

The Neighborhood

Photograph: Our Neighborhood Isn’t Just Your Toilet, It’s Our Photo Studio

Photograph: Poo-Flinger

Photograph: Garbage Dumped on Street

Photograph: Our street is not your personal trash dump.

Photograph: Free Library

5.

The Telephone

6.

The Internet

7.

Dating

Photograph: I Bet u LOOK GReAT NAKED ☺

8.

Going Places

Cars, sidewalks, public transportation, and airplanes

Photograph: Piggy Parker

Photograph: You park like you were badly raised.

Photograph: Car Parked on Street

9.

Eating, Drinking, Socializing

10.

Friends with Serious Illnesses

What to do when a friend is really, really sick and could maybe even die

11.

The Apology

12.

Trickle-Down Humanity

Photograph: My car couldn’t be more flattered.

Photograph: Note Under Windshield Wiper

Index

Also by Amy Alkon

Praise for the Author

About the Author

Copyright1

I DON’T CARE WHERE YOU PUT THE FORK

(as long as you don’t stab anybody in the eye with it)

This is not an etiquette book,

filled with prissy codes of conduct to help you fit in to upper-class society (or at least passably fake it), and I am nobody’s idea of an etiquette auntie. I don’t know the correct way to introduce an ambassador or address a wedding invite to a divorcée, and I’m not sure where to put the water glasses, other than “on the table.” I kept this to myself when I got a call from a TV producer from one of the national morning shows. She had seen me in a thirty-second bit about civility on the

Today

show, loved that I wasn’t the typical fusty etiquette expert, and—wow—wanted me to fly to New York to be the featured expert in a segment on “manners and civility at the holidays.”

“We’ll start with the table,” she said. “How to set it and how to properly serve the turkey.”

“Fantastic!” I lied—same as I would’ve if she’d asked me to come on national TV and stick my head up a horse’s ass to look for lost watches.

I do have a grasp on certain table manners basics, like that you shouldn’t lick your plate clean unless there’s a power outage or you’re dining with the blind, but I’m basically about as domestic as a golden retriever. I don’t cook; I heat. My dining room table is piled with books and papers. When my boyfriend makes me dinner, we eat balancing our plates on our legs while sitting on my couch. (Some men fantasize about kinky things to do in bed; he just wants to dine on a flat surface before we’re fed through tubes at The Home.)

My domestic failings aside, this was national TV, I needed to sell my book,

I See Rude People

, and I had a classy friend I could hit up for remedial table-setting and turkey-serving lessons. Of course, what I wanted to go on TV and say is what I actually think: What really matters isn’t how you set the table or serve the turkey but whether you’re nice to people while you’re doing it.

Two days before I was to board the plane to New York (on a nonrefundable ticket the network asked my publisher to pay for), I called the producer to double-check that I was prepared for my segment. “Uh … um … I’ll call you back in five minutes from my desk,” she said, and then she hung up. Two and a half hours later, I got an e-mail:

Subject: Saturday

In a message dated 12/8/10 12:22:01 PM,

[email protected] writes:

I just spoke to my executive producer who already had someone in mind for the segment. I am so sorry!

And I am really enthused about you and what you have to say, so let’s get you on the next time we have an etiquette segment.

Producer at unnamed network

Of course, I never heard from her again. (Out of guilt, people who’ve done crappy things to you tend to treat you like you’ve done something crappy to them.) On the bright side, they’d dumped me from the segment while I was still at home in Los Angeles, unlike a California author friend of mine who learned she’d been given the heave-ho when she logged on to her flight’s Wi-Fi over the Kansas cornfields.

Now, nobody owes me or anybody a spot on television, but when you’ve invited somebody to come on your show (especially your show on civility!), I do think you owe it to them to make sure you want them—and ideally, before they’ve booked a flight across the country on somebody else’s dime. At the very least, when these mistakes are made, you could work your way past that “

Eeeuw,

cooties!” feeling we get about somebody we’ve wronged and do something to make it up to them instead of just saying you will.

This experience got me thinking about how simple it actually is to treat other people well. Life is hardly one long Princess Cruise for any of us, and there are times when you’ll have to fire or disappoint somebody. But at the root of manners is empathy. When you’re unsure of what to say or do, there’s a really easy guideline, and it’s asking yourself,

Hey, self! How would I feel if somebody did that to me?

If everybody lived by this “Do Unto Others” rule—a beautifully simple rule we were supposed to learn in Kindergarten 101—I could probably publish this book as a twenty-page pamphlet. But so many people these days seem to be patterning their behavior on another simple rule, the “Up Yours” rule—“screw you if you don’t like it.” I lamented this behavioral shift in a

Los Angeles Times

op-ed featuring a mother flying with her toddler and a blasé attitude about his shrieking for over an hour before takeoff—so loudly that the safety announcements couldn’t be heard.

More and more, we’re all victims of these many small muggings every day. Our perp doesn’t wear a ski mask or carry a gun; he wears Dockers and shouts into his iPhone in the line behind us at Starbucks, streaming his dull life into our brains, never considering for a moment whether our attention belongs to him. These little acts of social thuggery are inconsequential in and of themselves, but they add up—wearing away at our patience and good nature and making our daily lives feel like one big wrestling smackdown.

The good news is, we

can

dial back the rudeness and change the way we all relate to one another, and we really need to, before rudeness becomes any more of a norm. That’s why I’ve written this book, a manners book for regular people. The term “nice people who sometimes say f*ck” describes people (like me and maybe you) who are well-meaning but imperfect, who sometimes lose their cool but try to be better the next time around, who sometimes swear (and maybe even enjoy it) but take care not to do it around anybody’s great-aunt or four-year-old.

In the pages that follow, I lay out my science-based theory that we’re experiencing more rudeness than ever because we recently lost the constraints on our behavior that were in place for millions of years of human history. I explain how we can reimpose those constraints and then tell you how not to be one of the rudewads and give you ways to stand up to the people who are.

Much of this surge in rudeness we’re experiencing is a consequence of life in The New Wild West, the world that technology made. Technology itself doesn’t cause the rudeness. But technological advances have led to sweeping social change, removing some of the consequences of being rude, especially in the past fifteen years, with so many people living states or continents apart from their families and friends, often spending their days in a swarm of strangers, and being both more and less connected than ever through cell phones, Facebook, Twitter, and Skype.

This book helps you take on and stop rudeness in these techno-spheres and other largely unregulated areas of our lives, such as our neighborhoods, where our society’s vastness and transience contribute to all sorts of piggy behavior in both public and private space. I use the term “unregulated” because there’s no cop you can call when somebody blogs what was supposed to be a private e-mail or when the lady in the apartment over yours spends the entire evening tap-dancing across her hardwood. To help you prevent situations like these and the cascade of miseries that can ensue, I map out ways for you to preemptively restrain the rude and solutions for when they start acting out.

In how I do this and in the advice I include,

Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck

sharply departs from the traditional manners advice books. Except for a few “in case you were raised by coyotes” tips on basic table manners, I’ve omitted picky etiquette stuff I’d only read at gunpoint, such as the correct way for married people to monogram their towels (a question which, per Google, is covered by a mere 19,400,000 web pages). Also, as I note in the “Eating, Drinking, Socializing” chapter, quite a bit of the advice given by traditional etiquette aunties is rather arbitrary, which is why one etiquette auntie advises that a lady may apply lipstick at the dinner table and another considers it an act only somewhat less taboo than squatting and taking a pee in the rosebushes. You’re simply supposed to memorize the particular auntie’s rules, and if you take issue with any, well, refer back to “Because I’m the mom!”