Granny's Wonderful Chair (Yesterday's Classics) (15 page)

Read Granny's Wonderful Chair (Yesterday's Classics) Online

Authors: Frances Browne

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction

" 'Buy a fiddle my young master?' he said, as Merrymind came forward. 'You shall have it cheap; I ask but a silver penny for it; and if the strings were mended, its like would not be in the north country.'

"Merrymind thought this a great bargain. He was a handy boy, and could mend the strings while watching his father's sheep. So down went the silver penny on the little man's stall, and up went the fiddle under Merrymind's arm.

" 'Now, my young master,' said the little man, 'you see that we merchants have a deal to look after, and if you help me to bundle up my stall, I will tell you a wonderful piece of news about that fiddle.'

"Merrymind was good-natured and fond of news, so he helped him to tie up the loose boards and sticks that composed his stall with an old rope, and when they were hoisted on his back like a fagot, the little man said:

" 'About that fiddle, my young master: it is certain the strings can never be mended, nor made new, except by threads from the night-spinners, which, if you get, it will be a good penny-worth'; and up the hill he ran like a greyhound.

"Merrymind thought that was queer news, but being given to hope the best, he believed the little man was only jesting, and made haste to join the rest of the family, who were soon on their way home. When they got there every one showed his bargain, and Merrymind showed his fiddle; but his brothers and sisters laughed at him for buying such a thing when he had never learned to play. His sisters asked him what music he could bring out of broken strings; and his father said:

" 'Thou hast shown little prudence in laying out thy first penny, from which token I fear thou wilt never have many to lay out.'

"In short, everybody threw scorn on Merrymind's bargain except his mother. She, good woman, said if he laid out one penny ill, he might lay out the next better; and who knew but his fiddle would be of use some day? To make her words good, Merrymind fell to repairing the strings—he spent all his time, both night and day, upon them; but, true to the little man's parting words, no mending would stand, and no string would hold on that fiddle. Merrymind tried everything, and wearied himself to no purpose. At last he thought of inquiring after people who spun at night; and this seemed such a good joke to the north country people, that they wanted no other till the next fair.

"In the meantime Merrymind lost credit at home and abroad. Everybody believed in his father's prophecy; his brothers and sisters valued him no more than a herd-boy; the neighbours thought he must turn out a scapegrace. Still the boy would not part with his fiddle. It was his silver pennyworth, and he had a strong hope of mending the strings for all that had come and gone; but since nobody at home cared for him except his mother, and as she had twelve other children, he resolved to leave the scorn behind him, and go to seek his fortune.

"The family were not very sorry to hear of that intention, being in a manner ashamed of him; besides, they could spare one out of thirteen. His father gave him a barley cake, and his mother her blessing. All his brothers and sisters wished him well. Most of the neighbours hoped that no harm would happen to him; and Merrymind set out one summer morning with the broken-stringed fiddle under his arm.

"There were no highways then in the north country—people took whatever path pleased them best; so Merrymind went over the fair ground and up the hill, hoping to meet the little man, and learn something of the night-spinners. The hill was covered with heather to the top, and he went up without meeting any one. On the other side it was steep and rocky, and after a hard scramble down, he came to a narrow glen all overgrown with wild furze and brambles. Merrymind had never met with briars so sharp, but he was not the boy to turn back readily, and pressed on in spite of torn clothes and scratched hands, till he came to the end of the glen, where two paths met; one of them wound through a pine-wood, he knew not how far, but it seemed green and pleasant. The other was a rough, stony way leading to a wide valley surrounded by high hills, and overhung by a dull, thick mist, though it was yet early in the summer evening.

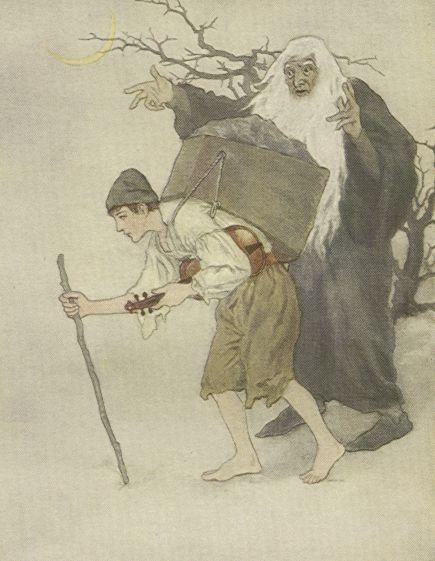

"Merrymind was weary with his long journey, and stood thinking of what path to choose, when, by the way of the valley, there came an old man as tall and large as any three men of the north country. His white hair and beard hung like tangled flax about him; his clothes were made of sackcloth; and on his back he carried a heavy burden of dust heaped high in a great pannier.

MERRYMIND AND HIS BURDEN.

" 'Listen to me, you lazy vagabond!' he said, coming near to Merrymind: 'If you take the way through the wood I know not what will happen to you; but if you choose this path you must help me with my pannier, and I can tell you it's no trifle.'

" 'Well, father,' said Merrymind, 'you seem tired, and I am younger than you, though not quite so tall; so, if you please, I will choose this way, and help you along with the pannier.'

"Scarce had he spoken when the huge man caught hold of him, firmly bound one side of the pannier to his shoulders with the same strong rope that fastened it on his own back, and never ceased scolding and calling him names as they marched over the stony ground together. It was a rough way and a heavy burden, and Merrymind wished himself a thousand times out of the old man's company, but there was no getting off; and at length, in hopes of beguiling the way, and putting him in better humour, he began to sing an old rhyme which his mother had taught him. By this time they had entered the valley, and the night had fallen very dark and cold. The old man ceased scolding, and by a feeble glimmer of the moonlight, which now began to shine, Merrymind saw that they were close by a deserted cottage, for its door stood open to the night winds. Here the old man paused, and loosed the rope from his own and Merrymind's shoulders.

" 'For seven times seven years,' he said, 'have I carried this pannier, and no one ever sang while helping me before. Night releases all men, so I release you. Where will you sleep—by my kitchen fire, or in that cold cottage?'

"Merrymind thought he had got quite enough of the old man's society, and therefore answered:

" 'The cottage, good father, if you please.'

" 'A sound sleep to you, then!' said the old man, and he went off with his pannier.

"Merrymind stepped into the deserted cottage. The moon was shining through door and window, for the mist was gone, and the night looked clear as day; but in all the valley he could hear no sound, nor was there any trace of inhabitants in the cottage. The hearth looked as if there had not been a fire there for years. A single article of furniture was not to be seen; but Merrymind was sore weary, and, laying himself down in a corner, with his fiddle close by, he fell fast asleep.

"The floor was hard, and his clothes were thin, but all through his sleep there came a sweet sound of singing voices and spinning-wheels, and Merrymind thought he must have been dreaming when he opened his eyes next morning on the bare and solitary house. The beautiful night was gone, and the heavy mist had come back. There was no blue sky, no bright sun to be seen. The light was cold and grey, like that of mid-winter; but Merrymind ate the half of his barley cake, drank from a stream hard by, and went out to see the valley.

"It was full of inhabitants, and they were all busy in houses, in fields, in mills, and in forges. The men hammered and delved; the women scrubbed and scoured; the very children were hard at work; but Merrymind could hear neither talk nor laughter among them. Every face looked careworn and cheerless, and every word was something about work or gain.

"Merrymind thought this unreasonable, for everybody there appeared rich. The women scrubbed in silk, the men delved in scarlet. Crimson curtains, marbled floors, and shelves of silver tankards were to be seen in every house; but their owners took neither ease nor pleasure in them, and everyone laboured as it were for life.

"The birds of that valley did not sing—they were too busy pecking and building. The cats did not lie by the fire—they were all on the watch for mice. The dogs went out after hares on their own account. The cattle and sheep grazed as if they were never to get another mouthful; and the herdsmen were all splitting wood or making baskets.

"In the midst of the valley there stood a stately castle, but instead of park and gardens, brew-houses and washing-greens lay round it. The gates stood open, and Merrymind ventured in. The courtyard was full of coopers. They were churning in the banquet hall. They were making cheese on the dais, and spinning and weaving in all its principal chambers. In the highest tower of that busy castle, at a window from which she could see the whole valley, there sat a noble lady. Her dress was rich, but of a dingy drab colour. Her hair was iron-grey; her look was sour and gloomy. Round her sat twelve maidens of the same aspect, spinning on ancient distaffs, and the lady spun as hard as they, but all the yarn they made was jet black.

"No one in or out of the castle would reply to Merrymind's salutations, nor answer him any questions. The rich men pulled out their purses, saying, 'Come and work for wages!' The poor men said, 'We have no time to talk!' A cripple by the wayside wouldn't answer him, he was so busy begging; and a child by a cottage door said it must go to work. All day Merrymind wandered about with his broken-stringed fiddle, and all day he saw the great old man marching round and round the valley with his heavy burden of dust.

" 'It is the dreariest valley that ever I beheld!' he said to himself. 'And no place to mend my fiddle in; but one would not like to go away without knowing what has come over the people, or if they have always worked so hard and heavily.'

"By this time the night again came on; he knew it by the clearing mist and the rising moon. The people began to hurry home in all directions. Silence came over house and field; and near the deserted cottage Merrymind met the old man.

" 'Good father,' he said, 'I pray you tell me what sport or pastime have the people of this valley?'

" 'Sport and pastime!' cried the old man, in great wrath. 'Where did you hear of the like? We work by day and sleep by night. There is no sport in Dame Dreary's land!' and, with a hearty scolding for his idleness and levity, he left Merrymind to sleep once more in the cottage.

"That night the boy did not sleep so sound; though too drowsy to open his eyes, he was sure there had been singing and spinning near him all night; and, resolving to find out what this meant before he left the valley, Merrymind ate the other half of his barley cake, drank again from the stream, and went out to see the country.

"The same heavy mist shut out sun and sky; the same hard work went forward wherever he turned his eyes; and the great old man with the dust-pannier strode on his accustomed round. Merrymind could find no one to answer a single question; rich and poor wanted him to work still more earnestly than the day before; and fearing that some of them might press him into service, he wandered away to the farthest end of the valley.

"There, there was no work, for the land lay bare and lonely, and was bounded by grey crags, as high and steep as any castle-wall. There was no passage or outlet, but through a great iron gate secured with a heavy padlock: close by it stood a white tent, and in the door a tall soldier, with one arm, stood smoking a long pipe. He was the first idle man Merrymind had seen in the valley, and his face looked to him like that of a friend; so coming up with his best bow, the boy said:

" 'Honourable master soldier, please to tell me what country is this, and why do the people work so hard?'

" 'Are you a stranger in this place, that you ask such questions?' answered the soldier.

" 'Yes,' said Merrymind; 'I came but the evening before yesterday.'

" 'Then I am sorry for you, for here you must remain. My orders are to let everybody in and nobody out; and the giant with the dust-pannier guards the other entrance night and day,' said the soldier.

" 'That is bad news,' said Merrymind; 'but since I am here, please to tell me why were such laws made, and what is the story of this valley?'

" 'Hold my pipe, and I will tell you,' said the soldier, 'for nobody else will take the time. This valley belongs to the lady of yonder castle, whom, for seven times seven years, men have called Dame Dreary. She had another name in her youth—they called her Lady Littlecare; and then the valley was the fairest spot in all the north country. The sun shone brightest there; the summers lingered longest. Fairies danced on the hill-tops; singing-birds sat on all the trees. Strongarm, the last of the giants, kept the pine-forest, and hewed yule logs out of it, when he was not sleeping in the sun. Two fair maidens, clothed in white, with silver wheels on their shoulders, came by night, and spun golden threads by the hearth of every cottage. The people wore homespun, and drank out of horn; but they had merry times. There were May-games, harvest-homes and Christmas cheer among them. Shepherds piped on the hill-sides, reapers sang in the fields, and laughter came with the red firelight out of every house in the evening. All that was changed, nobody knows how, for the old folks who remembered it are dead. Some say it was because of a magic ring which fell from the lady's finger; some because of a spring in the castle-court which went dry. However it was, the lady turned Dame Dreary. Hard work and hard times overspread the valley. The mist came down; the fairies departed; the giant Strongarm grew old, and took up a burden of dust; and the night-spinners were seen no more in any man's dwelling. They say it will be so till Dame Dreary lays down her distaff, and dances; but all the fiddlers of the north country have tried their merriest tunes to no purpose. The king is a wise prince and a great warrior. He has filled two treasure-houses, and conquered all his enemies; but he cannot change the order of Dame Dreary's land. I cannot tell you what great rewards he offered to any who could do it; but when no good came of his offers, the king feared that similar fashions might spread among his people, and therefore made a law that whosoever entered should not leave it. His majesty took me captive in war, and placed me here to keep the gate, and save his subjects trouble. If I had not brought my pipe with me, I should have been working as hard as any of them by this time, with my one arm. Young master, if you take my advice you will learn to smoke.'