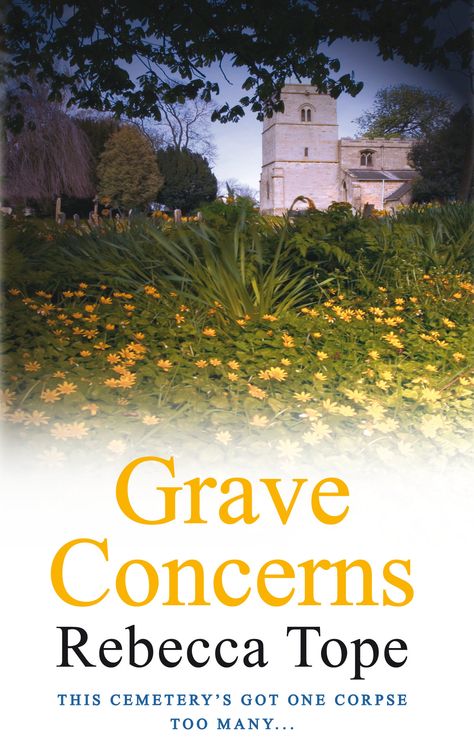

Grave Concerns

Authors: Rebecca Tope

REBECCA TOPE

For Adam, David,

Esther and Gemma

Title Page

Dedication

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

About The Author

By Rebecca Tope

Copyright

Advertisement

Caroline Kennett was dozing uncomfortably, her head lolling against the train window, her mouth insistently flopping open. She’d rushed to catch the last train and the effort had been exhausting in the August heat. Listening to Aunt Hilda moaning on about how forgetful Uncle George was becoming, and telling endless stories about all her friends and neighbours, had been hard work, too. All she wanted now was to get home and go to bed.

The train was sparsely occupied and seemed to be travelling at half speed. The lights had flickered on and off several times, giving the overall impression of a battery running down, a machine struggling to function. Outside it was dark, so she

had no idea where they were. Somewhere between Taunton and Exeter was all she knew.

Shaken awake by an unusually sharp jolt that banged her head painfully against the glass, she opened her eyes to total darkness. The train’s battery had obviously given up the ghost – or the line had leaves on it, or – or – the rail operators always had an inventive new excuse to hand. They juddered to a halt and a mechanical sigh of hopelessness was emitted from somewhere underneath Caroline’s seat.

Outside, it turned out not to be so dark after all. They were in the countryside, with hilly fields etched by the deep shadows of hedges and trees. A flickering darting light caught her attention.

Two figures were visible forty or fifty yards away in a field that sloped gently downhill from the railway line. Their pale featureless faces were turned towards the train and they seemed frozen into an unnatural immobility. One held a torch, the other some kind of implement. There were two darker patches on the ground nearby.

Caroline frowned, pressing her face to the window, trying to understand what she was seeing. Everything was monochrome, shapes in pale or dark grey. As her eyes adjusted and focused more clearly, the tableau began to make sense, to tell a story. One of the shapes on the ground was a mound of earth, presumably dug

by the implement – no doubt a spade. The second shape, almost identical in size and configuration, was – well, it

could have been

– a body.

The lights came on again without warning. The train began to move, slowly and gently. The scene receded into the realm of dream, another reality so distant and separate that Caroline had no feeling of responsibility or connection with it.

She imagined, vaguely, how it would be to tell the story. ‘I saw a body being buried in a field. It was somewhere in East Devon, I should think. We went through a station soon afterwards, but I couldn’t catch its name. Of course, it could have been a sheep or a large dog.’ She might say something to Jim, with a dismissive little laugh. Or she might just forget the whole thing.

‘Imagine a flower pushing up through a grave, fed by the organic matter below. This is a picture many of us cherish as a symbol of our own recycling – our bodies continuing in a different biological form.’

Drew paused and scanned the faces in front of him, letting the image gain favour, and overcome any shivers of distaste. The East Caddling Women’s Institute ladies were distinctly unsure about this whole subject, he could see. And indeed, his timing could have been better. Two days earlier, a coach carrying twenty-three Bradbourne school children had crashed in flames, killing eight precious youngsters. A

hurried consultation with the WI President had assured him there’d be no grieving grannies in his audience – but even so, it added to his nervousness.

One or two of the ladies were scowling at him, others were wide-eyed with agitation at his imprudent reference to dead bodies. He shook his head exaggeratedly, his face a picture of regret.

‘Unfortunately, at the present time at least, the idea of our bodies as fertiliser is pure fantasy. Burials as they are now practised are entirely useless as far as recycling is concerned. They’re too deep in the ground. The body is wrapped in a sheet of plastic and often embalmed. The coffin takes too long to disintegrate. Cremation might be a wicked waste of energy and organic matter – but burial is almost as bad.’

Small intakes of breath warned him that he was in danger of going too far. His own youth worked against him in some ways at times like this. He squared his shoulders confidently. He’d done this before and knew where the limits were, knew he reminded them of their own sons and thus invited maternal affection. Despite ladylike protests to the contrary, he also knew only too well how fascinated his audience was with what he had to say. With an average age of at least seventy-five, they had considerable personal investment in the subject. And it was a rare individual who

could honestly claim to have no interest in what happened to their mortal remains when the awful moment finally arrived.

‘It’s time we thought about changing this,’ he told them earnestly. ‘It’s time to help that image of the living flower on the grave to live once again …’

A movement at the back caught his attention. It was Maggs, standing close to the door, one finger raised as if trying to make a bid at Sotheby’s. She wagged it jerkily, the motion small but unmistakable. She wanted to speak to him, and urgently. He cocked an eyebrow at her and carried on with his speech. Three more minutes could make no difference to anything and there were points he still needed to get across.

‘Changes in the great rituals of life – and death – come slowly, and I am certainly not seeking to overturn any dearly-held notions. I’m simply trying to suggest that you give it some thought. Question your assumptions. For example, it isn’t true that cremation is cheaper, or more environmentally benign. Some societies choose cremation for social, environmental or religious reasons, but I am here to make a case for a return to burial, for many very similar reasons. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll take a short break, and return in five minutes for questions.’

* * *

Maggs was waiting for him at the back. He worked his way down one side of the crowded hall, smiling politely at anyone who caught his eye. When he reached his colleague, she took a pinch of his sleeve and led him into the small kitchen adjacent to the main hall. There she addressed him in a whisper.

‘There’s trouble at the field,’ she hissed. ‘You’ll have to come. Jeffrey insists on calling the police. I told him you’d be there in half an hour. That was’ – she glanced at her watch – ‘fifteen minutes ago.’

‘What sort of trouble?’

‘He’s found a body.’

Drew couldn’t help it. He laughed. Just one brief shout of amusement before taking control of himself. Maggs tightened her mouth. ‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘But you must admit it has a funny side. A dead body in a burial ground.’

‘It’s not funny, Drew. It’s disgusting. Jeffrey thinks it’s been dead for months. He found it with the metal detector.’

He glanced distractedly back towards the hall, aware of his unfinished presentation. ‘I can’t just leave,’ he said. ‘You know how important this is.’

‘Then it’s all right to call the police?’

‘Why not? Of course we should. Did you say

metal

detector?’

‘Yes – there’s some sort of necklace. I really

think you should be there. It’s your field.’ Her chubby face glared at him with the kind of reproach only found in girls of her age, when everything still seemed either entirely right or utterly wrong.

‘I’ll finish here in another twenty minutes. With any luck, the police won’t have arrived by the time I catch up with you.’

‘I’ll wait for you,’ she said. ‘Jeffery will have to manage without me.’

The audience’s questions were impressively direct. ‘Exactly how deep will your graves be?’ ‘What would a funeral cost, done your way?’ ‘Has anybody dear to you been buried in the way you advocate?’ and ‘Have you no respect for the dignity of death?’ This last came from a bristling woman in a blue felt hat that had to be forty years old. Some people groaned and one said, ‘Oh Marjorie!’

But Drew was delighted. He launched into an impassioned description of the awesomeness of death, how nobody could ever get used to it or properly understand it. He waxed lyrical about the serenity and beauty of a burial ground such as his would be. But Maggs would not allow him to go on. Her eyes remained fixed on him from beside the door at the back, and reluctantly he called a halt, made his excuses and left.

* * *

The field was seven miles away. Maggs led the way on her motor scooter, Drew following in his van, the narrow country lanes keeping his pace as slow as hers. They arrived to find Jeffrey standing beside the road, his face pale, muddy boots performing an agitated jig apparently of their own accord. Drew finally allowed himself to believe that something serious was happening. He jumped out of the van and addressed his gravedigger-cum-handyman.

‘What’s all this, Jeff? Did you call the police?’

The man nodded. ‘Should be here any moment. You took your time, didn’t you?’

‘I was busy,’ Drew said shortly. ‘You’re obviously coping well enough without me. Have you told Karen what’s going on?’

Jeffrey shook his head. ‘She’s not in.’

‘So where is it – this body?’ Drew looked into his field, where it sloped gently upwards from the road. Its acquisition had come about serendipitously, when a great-aunt had died a year before, leaving her village property to Drew’s mother, a year before. The cottage and adjoining ten acres of land were only a few miles from Bradbourne, where Drew and Karen had been living. Encouraged by Karen and his mother, Drew had wasted no time in putting into practice his ideas for a natural burial service. Increasingly uncomfortable working for a traditional

undertaker, he had leapt at the chance to set up on his own.

Three months ago, they had opened for business. Planning permission had been less difficult to obtain than they’d expected, and media interest had been substantial. Drew had been interviewed on local television and national radio, and continued to be in demand as a speaker. The inhabitants of the hamlet of North Staverton, being on the whole no-nonsense rustic folk with few anxieties about death and its trappings, had adapted to the change of use of Little Barn Field with surprising equanimity. Tucked away between the river and the railway, clustered around the large and relatively modern North Staverton Farm, a handful of properties already lived alongside herds of cows, flocks of sheep and fleets of tractors and agricultural machines passing through their single narrow street. Makeshift hearses and curious sightseers, attracted to Drew’s field from time to time, hardly bothered them.

The good-sized cottage had been adapted to comprise an office and ‘cool room’ with their own entrance, as well as living quarters for Drew and his family. A parking area for funeral business had been created and a tasteful sign painted.

Peaceful Repose Funerals. Natural Burial Ground. Proprietor: A. F. Slocombe

.

Gazing over his acres now, with the five initial graves clearly visible in the lower right-hand corner, Drew pondered the idea that a previous unauthorised burial had already taken place there, unbeknown to him or his partners. It brought a mixture of feelings: curiosity, annoyance, and an undercurrent of gratification. Somebody had sought out the much-publicised natural burial ground of their own accord; whatever the unpleasant truth of the matter turned out to be, it did at least show some sort of sensibility in their choice of a place to hide their inconvenient dead person.

‘How much have you uncovered?’ he asked. ‘Maggs seems to think it’s still got flesh on it.’

‘She’s right,’ grunted Jeffrey curtly. ‘Not that it’s sticking to the bones too well.’

Drew mentally dismissed the theory that had come to him in the van: that the body might be centuries old, something of historical rather than human interest. He made an inarticulate sound of disgust, tempered with professional acceptance. He’d seen many-months-dead bodies before, though only once or twice. They had not been very appealing.

Jeffrey pointed to a spot near the top of the slope where the ground was uneven and scattered with an early spring growth of nettles and thistles. Drew’s field was far from being a smooth green pasture – when he first acquired it, it had been chest-high

with weeds and riddled with rabbit holes. He could see where Jeffrey had been digging, the spade still sticking out of the dark loam.

‘There’s some sort of necklace – that’s what set my metal detector off,’ Jeffrey said. ‘It’s not down very deep, couple of feet at most. I unwrapped it down to the shoulders or thereabouts. Long white hair.’ The two men, followed closely by Maggs, were walking quickly up to the spot. Drew’s thoughts were fractured, skittering randomly around his head.

Why? Who? When?

He tried to piece together the story behind the discovery. What possible reason could there be, other than murder, for such a burial?

‘The police are going to want this like holes in their heads,’ he commented. ‘With all this school bus chaos. They’ve got eight post-mortems already – we’ll be lucky if they get to this one before next week.’

‘Trust you, Jeffrey,’ said Maggs. ‘Why’d you have to go and find it now?’

The gravedigger turned on her angrily. ‘Shut up, you – you—’

Drew put out a hand. ‘Come on, you two. Well, this is it, then,’ he continued, halting at the edge of Jeffrey’s digging and gazing down at what lay at his feet. ‘Looks like a woman,’ he said.

‘It is a woman,’ said Maggs, with youthful eagerness. ‘She’s wearing a sort of dress, see?

Funny how a bit of material can last longer than a person’s body. And that jewellery – I suppose that’d last forever.’

‘Jewellery might, but material wouldn’t,’ Drew remarked. ‘So it must be fairly recent. Pity it’s been such a wet winter – makes it much harder to estimate how long she’s been here.’

He was hardly aware of what he was saying, his gaze held by the uncovered head, revealing the uncompromising reality of what happens to human tissue when left under the ground for any length of time. Parts of the woman’s face had come away when Jeffrey had pulled the wrapping off it, so that grey bones showed here and there. Hanks of white hair stood out starkly against the red-brown soil.

‘Not a lot of point in a post-mortem,’ Drew went on. ‘Unless she was poisoned and they find arsenic in the hair, or she’s got broken bones, or she was shot and they find a bullet, I can’t see them ever finding a cause of death. There’s going to be a serious shortage of evidence on this one, you see if I’m not right.’

The police car was not sounding its siren, but they heard it approaching anyway. Very little road traffic passed Drew’s field in the middle of the day. ‘Here we go then,’ Drew said, taking a deep breath. ‘Brace yourselves.’

* * *

The police were initially highly efficient. They erected barriers around the impromptu grave, and summoned the Police Surgeon to supervise the slow and careful disinterment of the body. ‘She’s been well tucked in,’ Drew heard one of them remark. ‘Hands neatly folded. All laid out straight, too. Like a proper burial.’ Flashbulbs popped and every detail was recorded on tape.

Drew watched the whole process, feeling a sense of obligation to the corpse that he couldn’t have adequately explained. As the woman’s dead body was lifted free, one of the men lost his footing in the damp soil and let go. A faint ripping sound gave Drew’s guts a nasty twist. The material in which the body had been wrapped came loose, and the garment underneath was exposed. A knee-length dress, stained and shapeless, rode up over the body’s hips. The ripping sound had been that of decomposing skin and tissue separating at the sudden jolt. One leg dangled horribly, like that of a broken doll.

‘Christ!’ said the man who’d slipped, taking hold of the leg in gloved hands and trying to straighten it. ‘This is a right game.’

‘Better than those burnt kids,’ said his partner, holding tightly to the body’s shoulders.

‘You won’t forget this week in a hurry,’ Drew said sympathetically. ‘Why is it that everything happens at once?’

The police officer in charge consulted Drew about removing the body to the Pathology Lab. ‘You’re an undertaker,’ he said dubiously. ‘Maybe you could do it. Though we usually call Plant’s for Coroner’s removals.’

‘Call them if you like,’ said Drew. ‘I’m not going to argue.’ Despite the all-concealing plastic in which it was now being thoroughly wrapped, the body was far from pleasant to handle. But after a second’s reflection, he knew he should do it. The opportunity was too good to miss. Besides the payment, there was the chance to demonstrate that Peaceful Repose was a serious business, more than capable of tackling anything that Plant’s could do. ‘No – we’ll do it,’ he said. ‘It’d be daft to call Plant’s.’

‘Maggs!’ he called. ‘Get the van, would you? You can drive it part of the way up here at least.’ Throwing him a cheerful grin, she trotted off. Having failed her driving test for the second time only that week, she wasn’t qualified to drive on the road. But Drew let her practise on the smoother sections of the field, knowing how much she enjoyed it.