Gravity's Rainbow (79 page)

Authors: Thomas Pynchon

The house by the river is an enclosure that acts as a spring-suspension for the day

and the weather, allowing only mild cycling of light and heat, down into evening,

up again into morning to the midday peak but all damped to a gentle sway from the

earthquake of the day outside.

When Greta hears shots out in the increasingly distant streets, she will think of

the sound stages of her early career, and will take the explosions as cue calls for

the titanic sets of her dreams to be smoothly clogged with a thousand extras: meek,

herded by rifle shots, ascending and descending, arranged into patterns that will

suit the Director’s ideas of the picturesque—a river of faces, made up yellow and

white-lipped for the limitations of the film stock of the time, sweating yellow migrations

taken over and over again, fleeing nothing, escaping nowhere. . . .

It’s early morning now. Slothrop’s breath is white on the air. He is just up from

a dream. Part I of a poem, with woodcuts accompanying the text—a woman is attending

a dog show which is also, in some way, a stud service. She has brought her Pekingese,

a female with a sickeningly cute name, Mimsy or Goo-Goo or something, here to be serviced.

She is passing the time in a garden setting, with some other middle-class ladies like

herself, when from some enclosure nearby she hears the sound of her bitch, coming.

The sound goes on and on for much longer than seems appropriate, and she suddenly

realizes that the sound is her own voice, this interminable cry of dog-pleasure. The

others, politely, are pretending not to notice. She feels shame, but is helpless,

driven now by a need to go out and find other animal species to fuck. She sucks the

penis of a multicolored mongrel who has tried to mount her in the street. Out in a

barren field near a barbed-wire fence, winter fires across the clouds, a tall horse

compels her to kneel, passively, and kiss his hooves. Cats and minks, hyenas and rabbits,

fuck her inside automobiles, lost at night in the forests, out beside a water-hole

in the desert.

As Part II begins, she has discovered she’s pregnant. Her husband, a dumb, easygoing

screen door salesman, makes an agreement with her: her own promise is never stated,

but in return, nine months from now, he will take her where she wants to go. So it

is that close to the end of her term he is out on the river, an American river, in

a rowboat, hauling on the oars, carrying her on a journey. The key color in this section

is violet.

Part III finds her at the bottom of the river. She has drowned. But all forms of life

fill her womb. “Using her as mermaid” (line 7), they transport her down through these

green river-depths. “It was down, and out again./ Old Squalidozzi, ploughman of the

deep,/ At the end of his day’s sowing/ Sees her verdigris belly among the weeds” (lines

10–13), and brings her back up. He is a classically-bearded Neptune figure with an

old serene face. From out of her body streams a flood now of different creatures,

octopuses, reindeer, kangaroos, “Who can say all the life/ That left her womb that

day?” Squalidozzi can only catch a glimpse of the amazing spill as he bears her back

toward the surface. Above, it is a mild and sunlit green lake or pond, grassy at the

banks, shaded by willows. Insects whine and hover. The key color now is green. “And

there as it broke to sun/ Her corpse found sleep in the water/ And in the summer depths/

The creatures took their way/ Each to its proper love/ In the height of afternoon/

As the peaceful river went. . . .”

This dream will not leave him. He baits his hook, hunkers by the bank, drops his line

into the Spree. Presently he lights up an army cigarette, and stays still then for

a long while, as the fog moves white through the riverbank houses, and up above the

warplanes go droning somewhere invisible, and the dogs run barking in the back-streets.

• • • • • • •

When emptied of people, the interior is steel gray. When crowded, it’s green, a comfortable

acid green. Sunlight comes in through portholes in the higher of the bulkheads (the

Rücksichtslos

here lists at a permanent angle of 23° 27′), and steel washbowls line the lower bulkheads.

At the end of each sub-latrine are coffee messes and hand-cranked peep shows. You’ll

find all the older, less glamorous, un-Teutonic-looking women in the enlisted men’s

machines. The real stacked and more racially golden tomatoes go to the officers, natürlich.

This is some of that Nazi fanaticism.

The

Rücksichtslos

itself is the issue of another kind of fanaticism: that of the specialist. This vessel

here is a Toiletship, a triumph of the German mania for subdividing. “If the house

is organic,” argued the crafty early Toiletship advocates, “family lives in the house,

family’s organic, house is outward-and-visible sign, you see,” behind their smoked

glasses and under their gray crewcuts not believing a word of it, Machiavellian and

youthful, not quite ripe yet for paranoia, “and if the bathroom’s part of the house—house-is-organic!

ha-hah,” singing, chiding, pointing out the broad blond-faced engineer, hair parted

in the middle and slicked back, actually blushing and looking at his knees among the

good-natured smiling teeth of his fellow technologists because he’d been about to

forget that point (Albert Speer, himself, in a gray suit with a smudge of chalk on

the sleeve, all the way in the back leaning akimbo the wall and looking remarkably

like American cowboy actor Henry Fonda, has already forgotten about the house being

organic, and nobody points at him, RHIP). “Then the Toiletship is to the Kriegsmarine

as the bathroom is to the house. Because the Navy is organic, we all know that, ha-hah!”

[General, or maybe Admiral, laughter.] The Rücksichtslos was intended to be the flagship

of a whole Geschwader of Toiletships. But the steel quotas were diverted clear out

of the Navy over to the A4 rocket program. Yes, that does seem unusual, but Degenkolb

was heading up the Rocket Committee by then, remember, and had both power and will

to cut across all branches of the service. So the Rücksichtslos is one-of-a-kind,

old warship collectors, and if you’re in the market you better hurry ’cause GE’s already

been by to have a look. Lucky the Bolshies didn’t get it, huh, Charles? Charles, meantime,

is making on his clipboard what look like studious notes, but are really observations

of the passing scene such as They are all looking at me, or Lieutenant Rinso is plotting

to murder me, and of course the ever-reliable He’s one of them too and I’m going to

get him some night, well by now Charles’s colleague here, Steve, has forgotten about

the Russians, and discontinued his inspection of a flushing valve to take a really

close look at that Charles, you can’t pick your search team, not if you’re just out

of school and here I am, in the asshole of nowhere, not much more than a gofer to

this—what is he, a fag? What am I? What does GE want me to be? Is this some obscure

form of company punishment, even, good God, permanent exile? I’m a career man, they

can keep me out here 20 years if they want, ’n’ no-body’ll ever know, they’ll just

keep writing it off to overhead. Sheila! How’m I gonna tell Sheila? We’re engaged.

This is her picture (hair waved like choppy seas falling down Rita Hayworth style,

eyes that if it were a color snap would have yellow lids with pink rims, and a mouth

like a hot dog bun on a billboard). Took her out to Buf-falo Bayou,

Lookin’ for a little fun—

Big old bayou mosquito, oh my you

Shoulda seen what he done!

Poked his head up, under her dress,

Give a little grin and, well I guess,

Things got rough on Buf-falo Bayou,

Skeeter turn yer meter, down,

All—right—now!

Ya ta, ta-ta, ya-ta-ta, ta-ta

Lookin’ for a little fun,

Ev

-rybody!

Oh ya know, when you’re young and wholesome [“Ev’rybody,” in this case a Toiletshipload

of bright hornrimmed shoe-pac’d young fellas from Schenectady, are singin’ along behind

this recitative here] and a good church-goin’ kid, it’s sure a mournful thing to get

suddenly ganged by a pack of those Texas mosquitoes, it can set you back 20 years.

Why, there’s boys just like you wanderin’ around, you may’ve seen one in the street

today and never known it, with the mind of a infant, just because those mosquitoes

got to him and did their unspeakable thing. And we’ve laid down insecticides, a-and

bombed the bayous with citronella, and it’s no good, folks. They breed faster’n we

can kill ’em, and are we just gonna tuck tail and let them

be

there out in Buffalo Bayou where my gal Sheila had to look at the loathsome behavior

of those—things, we gonna allow them even to

exist?

—And,

Things got rough on, Buf-falo Bayou,

Skeeter turn yer meter, down,

Hubba hubba—

Skeeter turn yer meter, down!

Well, you can’t help but wonder who’s really the more paranoid of the two here. Steve’s

sure got a lot of gall badmouthing Charles that way. Among the hilarious graffiti

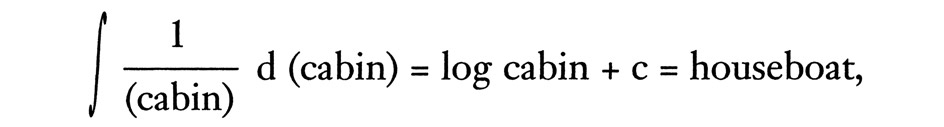

of visiting mathematicians,

that sort of thing, they go poking away down the narrow sausage-shaped latrine now,

two young/old men, their feet fade and cease to ring on the sloping steel deck, their

forms grow more transparent with distance until it’s impossible to see them any more.

Only the empty compartment here, the S-curved spokes on the peep-show machines, the

rows of mirrors directly facing, reflecting each other, frame after frame, back in

a curve of very great radius. Out to the end of this segment of curve is considered

part of the space of the

Rücksichtslos.

Making it a rather fat ship. Carrying its right-of-way along with it. “Crew morale,”

whispered the foxes at the Ministry meetings, “sailors’ superstitions. Mirrors at

high midnight.

We

know, don’t we?”

The officers’ latrines, by contrast, are done in red velvet. The decor is 1930s Safety

Manual. That is, all over the walls, photograffiti, are pictures of Horrible Disasters

in German Naval History. Collisions, magazine explosions, U-boat sinkings, just the

thing if you’re an officer trying to take a shit. The Foxes have been busy. Commanding

officers get whole suites, private shower or sunken bathtub, manicurist (BDM volunteers,

mostly), steam room, massage table. To compensate though, all the bulkheads, and the

overhead, are occupied by enormous photographs of Hitler at various forms of play.

The toilet paper! The toilet paper is covered square after square with caricatures

of Churchill, Eisenhower, Roosevelt, Chiang Kai-shek, there was even a Staff Caricaturist

always on duty to custom-illustrate blank paper for those connoisseurs who are ever

in search of the unusual. Wagner and Hugo Wolf were patched into speakers from up

in the radio shack. Cigarettes were free. It was a good life on board the Toiletship

Rücksichtslos

, as it plied its way from Swinemünde to Helgoland, anyplace it was needed, camouflaged

in shades of gray, turn-of-the-century style with sharp-shadowed prows coming at you

from midships so you couldn’t tell which way she was headed. Ship’s company actually

lived each man inside his stall, each with his own key and locker, pin-ups and library

shelves decorating the partitions . . . and there were even one-way mirrors so you

could sit at your ease, penis dangling toward the ice-cold seawater in your bowl,

listen to your VE-301 People’s Receiver, and watch the afternoon rush, the busy ringing

of feet and talk, card games inside the group toilets, dealers enthroned on real porcelain

receiving visitors, some of them lined up back outside the compartment (quiet queues,

all business, something like the queues in banks), toilet-lawyers dispensing advice,

all kinds of visitor coming and going, the U-boat crews hunching in, twitching eyes

nervously every second or two at the overhead, destroyer sailors larking at the troughs

(

gigantic

troughs! running the whole beam of the ship, even, legend has it, off into mirror-space,

big enough to seat 40 or 50 aching assholes side by side, while a constant river of

salt flushing water roared by underneath), lighting wads of toilet paper, is what

they especially liked to do, setting them flaming yellow in the water upstream and

cackling with glee as one by one down the line the sitters leaped off the holes screaming

and clutching their blistered asses and inhaling the smell of singed pubic hair. Not

that the crew of the Toiletship itself were above a practical joke now and then. Who

can ever forget the time shipfitters Höpmann and Kreuss, at the height of the Ptomaine

Epidemic of 1943, routed those waste lines into the ventilation system of the executive

officer’s stateroom? The exec, being an old Toiletship hand, laughed good-naturedly

at the clever prank and transferred Höpmann and Kreuss to icebreaker duty, where the

two Scatotechnic Snipes went on to erect vaguely turd-shaped monoliths of ice and

snow all across the Arctic. Now and then one shows up on an ice floe drifting south

in ghostly grandeur, exciting the admiration of all.