Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (2 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

Neither theme, it turns out, can be explained without reference to his long apprenticeship in South Africa, where he eventually defined himself as leader of a mass movement. My aim is to amplify rather than replace the standard narrative of the life Gandhi led on two subcontinents by dwelling on incidents and themes that have often been underplayed. It isn’t to diminish a compelling figure now generally exalted as a spiritual pilgrim and secular saint. It’s to take a fresh look, in an attempt to understand his life as he lived it. I’m more fascinated by the man himself, the long arc of his strenuous life, than by anything that can be distilled as doctrine.

Gandhi offered many overlapping and open-ended definitions of his

highest goal, which he sometimes defined as

poorna swaraj

.

*

He wasn’t the one who’d introduced

swaraj

into the political lexicon, a term usually translated as “self-rule” while Gandhi still lived in South Africa. Later it would be expanded to mean “independence.” As used by Gandhi, poorna swaraj put the goal on yet a higher plane. At his most utopian, it was a goal not just for India but for each individual Indian; only then could it be

poorna

, or complete. It meant a sloughing not only of British rule but of British ways, a rejection of modern industrial society in favor of a bottom-up renewal of India, starting in its villages, 700,000 of them, according to the count he used for the country as it existed before its partition in 1947. Gandhi was thus a revivalist as much as a political figure, in the sense that he wanted to instill values in India’s most recalcitrant, impoverished precincts—values of social justice, self-reliance, and public hygiene—that nurtured together would flower as a material and spiritual renewal on a national scale.

Swaraj, said this man of many causes, was like a banyan tree, having

“innumerable trunks each of which is as important to the tree as the original trunk.” He meant it was bigger than the struggle for mere independence.

“He increasingly ceased to be a serious political leader,” a prominent British scholar has commented. Gandhi, who formally resigned from the Indian National Congress as early as 1934 and never rejoined it, might have agreed. If the leader succeeded in driving the colonists out but his revival failed, he’d have to count himself a failure. Swaraj had to be for all Indians, but in his most challenging formulations he said it would be especially for

“the starving toiling millions.”

It meant, he said once, speaking in this vein,

“the emancipation of India’s skeletons.” Or again: “Poorna swaraj denotes a state of things in which the dumb begin to speak and the lame begin to walk.”

The Gandhi who held up this particular standard of social justice as an ultimate goal wasn’t always consistent or easy to follow in his discourse, let alone his campaigns. But this is the Gandhi whose words still have a power to resonate in India. And this vision, always with him a work in progress, first shows up in South Africa.

Today most South Africans and Indians profess reverence for the Mahatma, as do many others across the world. But like the restored Phoenix Settlement, our various Gandhis tend to be replicas fenced off

from our surroundings and his times. The original, with all his quirkiness, elusiveness, and genius for reinvention, his occasional cruelty and deep humanity, will always be worth pursuing. He never worshipped idols himself and generally seemed indifferent to the clouds of reverence that swirled around him. Always he demanded a response in the form of life changes. Even now, he doesn’t let Indians—or, for that matter, the rest of us—off easy.

*

Indian and other foreign terms are italicized on their first appearance and defined in a glossary starting on

this page

.

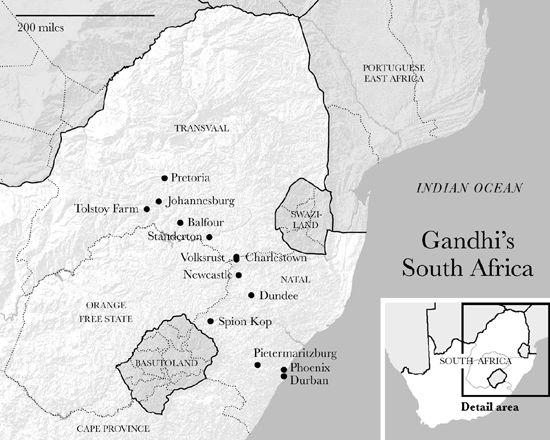

SOUTH AFRICA

PROLOGUE: AN UNWELCOME VISITOR

I

T WAS A BRIEF

only a briefless lawyer might have accepted. Mohandas Gandhi landed in

South Africa as an untested, unknown

twenty-three-year-old law clerk brought over from Bombay, where his effort to launch a legal career had been stalled for more than a year. His stay in the country was expected to be temporary, a year at most. Instead, a full twenty-one years elapsed before he made his final departure on July 14, 1914. By then, he was forty-four, a seasoned politician and negotiator, recently leader of a mass movement, author of a doctrine for such struggles, a pithy and prolific political pamphleteer, and more—a self-taught evangelist on matters spiritual, nutritional, even medical. That’s to say, he was well on his way to becoming the Gandhi India would come to revere and, sporadically, follow.

None of that was part of the original job description. His only mission at the outset was to assist in a bitter civil suit between two Muslim trading firms with roots of their own in Porbandar, the small port on the Arabian Sea, in the northwest corner of today’s India, where he was born. All the young lawyer brought to the case were his fluency in English and Gujarati, his first language, and his recent legal training at the Inner Temple in London; his lowly task was to function as an interpreter, culturally as well as linguistically, between the merchant who engaged him and the merchant’s English attorney.

Up to this point there was no evidence of his ever having had a spontaneous political thought. During three years in London—and the nearly two years of trying to find his feet in India that followed—his causes were dietary and religious:

vegetarianism and the mystical cult

known as

Theosophy, which claimed to have absorbed the wisdom of the East, in particular of Hinduism, about which Gandhi, looking for footholds on a foreign shore, had more curiosity then than scriptural knowledge himself. Never a mystic, he found fellowship in London with other seekers on what amounted, metaphorically speaking, to a small weedy fringe, which he took to be common ground between two cultures.

South Africa, by contrast, challenged him from the start to explain what he thought he was doing there in his brown skin. Or, more precisely, in his brown skin, natty frock coat, striped pants, and black turban, flattened in the style of his native Kathiawad region, which he wore into a magistrate’s court in Durban on May 23, 1893, the day after his arrival. The magistrate took the headgear as a sign of disrespect and ordered the unknown lawyer to remove it; instead, Gandhi stalked out of the courtroom. The small confrontation was written up the next day in

The Natal Advertiser

in a sardonic little article titled “An Unwelcome Visitor.” Gandhi immediately shot off a letter to the newspaper, the first of dozens he’d write to deflect or deflate white sentiments. “

Just as it is a mark of respect amongst Europeans to take off their hats,” he wrote, an Indian shows respect by keeping his head covered. “In England, on attending drawing-room meetings and evening parties, Indians always keep the head-dress, and the English ladies and gentlemen seem to appreciate the regard which we show thereby.”

The letter saw print on what was only the fourth day the young nonentity had been in the land. It’s noteworthy because it comes nearly two weeks

before

a jarring experience of racial insult, on a train heading inland from the coast, that’s generally held to have fired his spirit of resistance. The letter to the

Advertiser

would seem to demonstrate that Gandhi’s spirit didn’t need igniting; its undertone of teasing, of playful jousting, would turn out to be characteristic. Yet it’s the train incident that’s certified as transformative not only in

Richard Attenborough’s film

Gandhi

or

Philip Glass’s opera

Satyagraha

but in Gandhi’s own

Autobiography

, written three decades after the event.

If it wasn’t character forming, it must have been character arousing (or deepening) to be ejected, as Gandhi was at Pietermaritzburg, from a first-class compartment because a white passenger objected to having to share the space with a “coolie.” What’s regularly underplayed in the countless renditions of the train incident is the fact that the agitated young lawyer eventually got his way. The next morning he fired off telegrams to the general manager of the railway and his sponsor in Durban.

He raised enough of a commotion that he finally was allowed to reboard the same train from the same station the next night under the protection of the stationmaster, occupying a first-class berth.

The rail line didn’t run all the way to Johannesburg in those days, so he had to complete the final leg of the trip by stagecoach. Again he fell into a clash that was overtly racial. Gandhi, who’d refrained from making a fuss about being seated outside on the coach box next to the driver, was dragged down at a rest stop by a white crewman who wanted the seat for himself. When he resisted, the crewman called him a “sammy”—a derisive South African epithet for Indians (derived from “swami,” it’s said)—and started thumping him. In Gandhi’s retelling, his protests had the surprising effect of rousing sympathetic white passengers to intervene on his behalf. He manages to keep his seat and, when the coach stops for the night, shoots off a letter to the local supervisor of the stagecoach company, who then makes sure that the young foreigner is seated inside for the final stage of the journey.

All the newcomer’s almost instantaneous retorts in letters and telegrams tell us that young Mohan, as he would have been called, brought his instinct for resistance (what the psychoanalyst

Erik Erikson called his “

eternal negative”) with him to South Africa. Its alien environment would prove a perfect place for that instinct to flourish. In what was still largely a frontier society, the will to white domination had yet to produce a settled racial order. (It never would, in fact, though the attempt would be systematically made.) Gandhi would not have to seek conflict; it would find him.

In these bumpy first days in a new land, Mohan Gandhi comes across on first encounters as a wiry, engaging figure, soft-spoken but not at all reticent. His English is on its way to becoming impeccable, and he’s as well dressed in a British manner as most whites he meets. He can stand his ground, but he’s not assertive or restless in the sense of seeming unsettled. Later he would portray himself as having been shy at this stage in his life, but in fact he consistently demonstrates a poise that may have been a matter of heritage: he’s the son and grandson of

diwans

, occupants of the top civil position in the courts of the tiny princely states that proliferated in the part of Gujarat where he grew up. A diwan was a cross between a chief minister and an estate manager. Gandhi’s father evidently failed to dip into his rajah’s coffers for his own benefit and remained a man of modest means. But he had status, dignity, and assurance to bequeath. These attributes in combination with his brown skin and his credentials as a London-trained barrister are enough to mark the

son as unusual in that time and place in South Africa: for some, at least, a sympathetic, arresting figure.

He’s susceptible to moral appeals and ameliorative doctrines but not particularly curious about his new surroundings or the tangle of moral issues that are as much part of the new land as its hardy flora. He has left a wife and two sons behind in India and has yet to import the string of nephews and cousins who’d later follow him to South Africa, so he’s very much on his own. Because he failed to establish himself as a lawyer in Bombay, his temporary commission represents his entire livelihood and that of his family, so he can reasonably be assumed to be on the lookout for ways to jump-start a career. He wants his life to matter, but he’s not sure where or how; in that sense, like most twenty-three-year-olds, he’s vulnerable and unfinished. He’s looking for something—a career, a sanctified way of life, preferably both—on which to fasten. You can’t easily tell from the autobiography he’d dash off in weekly installments more than three decades later, but at this stage he’s more the unsung hero of an East-West bildungsroman than the Mahatma in waiting he portrays who experiences few doubts or deviations after his first weeks in London before he turned twenty.

The Gandhi who landed in South Africa doesn’t seem a likely recipient of the spiritual honorific—“Mahatma” means “Great Soul”—that the poet

Rabindranath Tagore affixed to his name years later, four years after his return to India. His transformation or self-invention—a process that’s as much inward as outward—takes years, but once it’s under way, he’s never again static or predictable.

Toward the end of his life, when he could no longer command the movement he’d led in India, Gandhi found words in a Tagore song to express his abiding sense of his own singularity: “

I believe in walking alone. I came alone in this world, I have walked alone in the valley of the shadow of death, and I shall quit alone, when the time comes.” He wouldn’t have put it quite so starkly when he landed in South Africa, but he felt himself to be walking alone in a way he could hardly have imagined had he remained in the cocoon of his Indian extended family.