Greece, the Hidden Centuries: Turkish Rule From the Fall of Constantinople to Greek Independence (14 page)

Authors: David Brewer

Tags: #History / Ancient

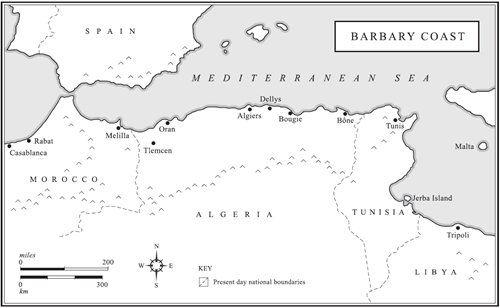

We should not conclude, even after this demolition of some of the Barbary myths, that its main port at Algiers was a normal and well-ordered city under an enlightened governor, and whose inhabitants went legally and peacefully about their business. From the 1560s onwards raiders from the Barbary coast were seizing ships and plundering coasts over virtually the whole Mediterranean. Their success was due to two developments. One was the formation of large fleets: eight or nine armed ships, for whom an isolated target vessel was easy prey, and later these fleets might contain as many as 40 ships. The other novelty was the replacement, from about 1580, of oared galleys by light fast sailing ships of the type developed by Christian powers for use in the Atlantic. Between 1613 and 1621 raiders brought back to Algiers nearly 900 captive ships, half of them Dutch and the rest French, Spanish, English or German.

However, a distinction needs to be drawn between Algerian raiders and raiders from other countries who used Algiers as their base because it was a centre for trade in plundered cargoes and captives. This distinction was often ignored by contemporaries, who regarded any ship originating from Algiers as an Algerian pirate. When the distinction was made it often favoured the Algerians: it was the foreigners in Algiers who were described as ‘the most cruel villains in Turkie and Barbary’, while the Algerians were ‘very noble, and of good nature, in comparison to them’.

7

Virtually all the Christian powers contributed to this international sea raiding in the Mediterranean: Spain, France, Holland and England, (often seen as the most active) as well as the semi-independent bodies of the Knights of St John, based in Rhodes and later Malta, and the Knights of San Stefano based in Livorno. It has been maintained that at the beginning of the seventeenth century piracy of various kinds

had virtually brought Mediterranean sea trade to a standstill. Venice in particular suffered. In 1580 Venice lost 25 ships to raiders from Barbary in about a month on the Dalmatian coast alone, and in 1603 raiders from Naples and Sicily cost Venice the loss of an estimated eight million ducats in a year. So marine insurance rates shot up, from about 2 to 40 per cent or even higher, and ships stayed in dock ‘in lamentable idleness’ because nobody would insure them even at the highest rates. A 1607 letter to the Doge from his brother maintained that ‘Trade is suspended, you suffer loss of revenue and duties, shipbuilding ceases, we lose our sailors, and victuals are imported with difficulty. The government is dishonoured, the merchants speak ill of it, some talk of emigrating and everyone is scandalized.’

8

Venice was probably not typical. Other states took more effective measures to protect their Mediterranean shipping, and in any case trade cannot have ceased altogether or piracy, with no ships to plunder, would have stopped with it. But there is no doubt that for much of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries piracy was a crucial factor over the whole of the Mediterranean.

The Greeks too were drawn into the world of piracy. Greek sailors are often mentioned among the crews of foreign raiding vessels, and they began to practise small-scale piracy themselves. The French naturalist Pierre Belon, visiting the Aegean islands in the 1550s, saw ‘three or four men, accustomed to the sea, boldly pursuing the life of adventure, poor men, with only a small barque or frigate or perhaps some ill-equipped brigantine: but they have their bussolo or mariner’s compass to navigate by and also the means to wage war, that is a few small arms for firing at a little distance. Their rations are a sack of flour, some biscuit, a skin of oil, honey, a few bunches of garlic and onions and a little salt and on these they support themselves for a month. Thus armed they set out in search of prey.’

9

Greek seamen continued to serve on the raiders of other states, and in 1740 the first Greek captain of such a ship is recorded: Panayiótis Christópoulos, from Zákinthos, who commanded first a ship from Malta under the direction of the Knights of St John, and then an English-built ship flying the British flag. Later, in the war of 1789–92 between Turkey and Russia, Lámbros Katsónis from Livadhiá commanded against the Turks a flotilla of eighteen ships, flying the Russian flag but with crews of Greek islanders. After the war ended Katsónis turned pirate, and in the words of the bishop of Skiáthos, ‘he began to plunder and lay waste the Turkish islands, extending his pirate activity even to the islands of my humble bishopric of Skiáthos by seizing ships and men whom he kept captive.’

10

Still under Russian colours, he also plundered French

and Venetian vessels, though the Russians forced him to return much of his booty. The Turks eventually cornered him at Pórto Káyio, the tiny rock-bound harbour at the southern tip of the Mani. He escaped to the Ionian islands and finally to Russia, bitterly accusing the Russians of failing to support him or to appreciate his contribution to their war.

By the late eighteenth century a new form of Greek piracy had developed. Land-based brigands would seize a ship to attack other ships or plunder the neighbouring coast, and when attacked would flee back to the land. In 1775 a Greek pirate named Karamóschos was raiding the coasts of Kasándhra east of Thessalonika. A Turkish flotilla captured his ships and killed most of the crews, and the few who escaped fled to the mountains of the interior. The pirates were as much a menace to the local Greeks as to the Turks, and the villagers promised in sworn statements to cooperate against the pirates, though under an element of duress: if they failed to do so the village leaders were threatened with heavy fines or death.

Twenty years later Greek pirates were bolder still, seizing all the ships in Vólos harbour and using them for piracy for three years. As before, when attacked by Turkish ships the pirates fled to the land, and the orders from Constantinople stressed that the villagers should not be alienated: ‘You are not to harm at all any innocent inhabitants during this campaign.’

11

But this form of piracy seems nevertheless to have grown and the Turkish authorities to be more ready to grant amnesty. In 1809 a band of pirates said to number about 600, with 400 dependants, was active near the island of Spétses. When blockaded by Turkish ships the pirates surrendered, were granted pardon and resettled in their own villages. After Greek independence it was the Greek government that had to deal with piracy and both Miaoúlis and Kanáris, naval heroes of the independence war, were sent to suppress it. The final flourish of Greek piracy was in 1854 in north-east Greece, then still under Turkish rule, in a failed attempt to take advantage of Turkey’s difficulties in the Crimean war to achieve immediate independence for the region.

Just as ‘pirates’ could mean different things in different contexts, so too there was no single category of slaves. The Turkish word ‘kul’ could mean a literal slave – somebody’s property to be bought and sold, and having no rights – or very broadly any tax-paying subject of the Sultan; or very narrowly the Sultan’s personal servants, the kapikullari or Slaves of the Porte, from palace gardener up to grand vizier and including the janissary soldiers. Similarly ‘kulluk’ could mean literal slavery, or simply the obligation to provide labour or to pay certain taxes.

The most privileged of those called slaves were the Slaves of the Porte, with the grand vizier at the apex. A grand vizier of Suleyman the Magnificent described himself as ‘the weakest of God’s slaves’.

12

These Slaves of the Porte were originally prisoners of war, or had been brought in by the devshirme conscription, or came from the slave markets. But even the grand vizier was a slave in that he was absolutely subject to the Sultan’s will, and the seventeenth-century traveller Jean de Thévenot describes how the Sultan disposed of a grand vizier who had lost favour, and how readily the vizier submitted to his fate: ‘A messenger arrives and shows him the order he has to bring the man’s head; the latter takes this order from the Great Lord, kisses it, places it upon his head as a sign of the respect he bears for the order, makes his ablutions and says his prayers, after which he freely lays down his head.’

13

It was a not uncommon end, and few grand viziers died in their beds.

At the bottom of the ladder of privilege were galley slaves. They might be captives in war or from coastal raids, or sometimes criminals, who were condemned to the oar in both Muslim and Christian states. These were very unsatisfactory sources of manpower: many had no experience of the sea, and neither category had any loyalty to the ship on which they served. The remedy was twofold: to hire free volunteers as well as those forced into service, and to command by fear.

Many accounts of service in the galleys are indeed fearsome. A war captive, Baron von Mitrovic, was a galley slave on a Turkish ship in the 1590s and later wrote:

The torment of rowing in a galley is unbelievable in extent. No other work on earth is harder because each prisoner has one of his legs fastened to a chain underneath the seat and can move no further than is necessary for him to reach his rowing place on the bench. The heat is so stifling that it is impossible to row other than in the nude or just a pair of flaxen pants. Iron handcuffs are clamped on to the hands of each man so that he is able neither to resist the Turk nor defend himself. His hands and legs thus shackled, the captive can do no more than row day and night, except when the sea is rough, until his skin becomes burned like that of a roasted pig and finally cracks from the heat. Sweat runs into his eyes and saturates his body, causing that peculiar agony of blistered hands. But the ship’s speed must not slacken, which is why, whenever the captain notices anyone stopping to draw breath, he lashes out with a slave whip or a rope dripping wet from seawater until the rower’s body is covered in blood. All the food you get is two small pieces of hardtack. Only when we arrived at islands inhabited by Christians could we sometimes ask for, or buy, if we had any money, a little wine and sometimes

a little soup. Whenever we rode at anchor for one, two, three, or more days, we knitted cotton gloves and socks and sold them for a little extra food that we cooked on board. Life on board was so utterly dismal and execrable that it was worse than death.

14

There was welcome respite for the galley slaves in winter when the ships were in port, and the oarsmen were put to other work in the dockyards. But in view of the testimony of Mitrovic and many others, it is difficult to accept the statement of a distinguished historian of the period, that ‘the black romanticism of rowers chained to the galleys should be ascribed to fiction.’

15

That is true only in so far as the plight of galley slaves has been used in fiction or dramatised history. An impressive example of this was the French film of the 1940s,

Père Vincent

, about the seventeenth-century priest Vincent de Paul, later canonised, who served as almoner-general to the galleys. The film had a contemporary message: the galley slaves represented all the Frenchmen recently deported for forced labour by the occupying Germans.

Between these two extremes of elevation at the Sultan’s court and degradation in the galleys, slaves were used in other ways. Male slaves were used for construction work on buildings or roads, or worked on the estates of landowners. There were few if any plantation slaves, as used to harvest sugar in the Caribbean or cotton in the southern United States, since Mediterranean products did not generally need such a labour force. Probably the majority of slaves, both male and female, found themselves in domestic service.

It is impossible to say how far female domestic slaves were sexually exploited. It undoubtedly occurred, but there were limitations: for instance a female slave belonging to a woman could not be touched by her husband. Also there were many instances of female slaves being well treated, if not honoured, in a Turkish household. A freed slave might be married by her former master or benefit from his will, or slaves could even become executors of the will. When considering sexual exploitation we should not be too much influenced by the fact that youth and beauty in a female slave commanded a higher price; a young servant would be a better worker, and a pretty one a more impressive adornment of the household.

For the Turks there were two main sources of slaves: prisoners of war and the Crimean slave trade. The prisoners were taken in the wars between the Ottoman Empire and the non-Muslims on her borders. In the 1550s Ogier de Busbecq, the Habsburg emissary to Constantinople, saw a procession of such captives: ‘Just as we were leaving the city, we

were met by wagon-loads of boys and girls who were being brought from Hungary to be sold in Constantinople. There is no commoner kind of merchandise than this in Turkey, and from time to time we were met by gangs of wretched Christian slaves of every kind who were being led to horrible servitude. Youths and men of advanced years were driven along in herds or else were tied together with chains, as horses with us are taken to market, and trailed along in a long line. At the sight I could scarcely restrain my tears in pity for the wretched plight of the Christian population.’

16