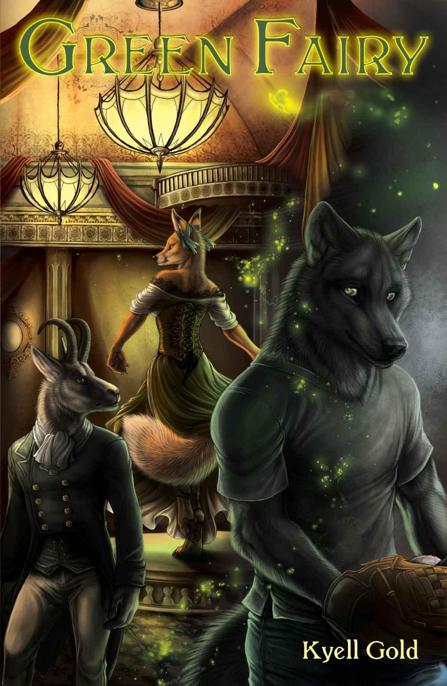

Green Fairy (Dangerous Spirits)

Read Green Fairy (Dangerous Spirits) Online

Authors: Kyell Gold

GREEN FAIRY

by Kyell Gold

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed within are fictitious.

GREEN FAIRY

Copyright 2012 by Kyell Gold

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

Published by Sofawolf Press

St. Paul, Minnesota

http://www.sofawolf.com

ISBN 978-1-936689-16-3

Printed in the United States of America

First trade paperback edition: March 2012

Cover art by Rukis

For foozzzball, who brings Montmartre to me.

Even without the absinthe.

Table of Contents

Sol was only reading a news story about a college student who’d killed himself, but the student had been gay, so when the young wolf’s fur prickled with the feeling of someone staring at him, he hid the story behind the picture of a car on a local auto dealer’s website. The quick keystroke had become as reflexive as twitching his tail or ears, even though his parents had never caught him looking at gay pictures or reading gay stories.

The feeling of being watched usually went along with either that or texting his boyfriend—his four-hour-away different-species secret boyfriend—and he was certainly waiting for Carcy to reply to his last text. But this was stronger, this was a presence behind him. Even after he’d turned and made sure nobody had climbed up the side of his house to stare in his second-story bedroom window, even after he’d sniffed every corner of the room and caught nothing but the constant background of his own scent, his parents, and the seven-month old scent of his brother, the feeling persisted. He couldn’t get through more than a paragraph of the story before sniffing over his shoulder again, so he gave up.

If his parents did catch him reading the story, he could’ve told them it was because of his cousin, and that would not have been a complete lie. It was just close enough to the truth that it might raise awkward questions. They might send him to a priest or a counselor to “answer his questions about homosexuality,” or, God forbid, try to have a talk with him themselves.

His phone buzzed, jolting him back to reality. There was nobody in the room, nobody watching him through the window, but his fur still prickled with the feeling. He tried to ignore it as he picked up the phone to see what Carcy had said.

What does it matter? School’s over in three months anyway.

Which was true. And then…Sol drank in the picture of the car, staring at it until he could see himself behind the wheel, driving four hours up to Millenport.

And then I’ll get to see you

, he typed.

Yep. :) And what your dad thinks doesn’t matter here.

It would still matter that Sol was gay. But his dad wouldn’t have to know that, even then, maybe ever. What mattered right now was what his dad would think about Sol losing his starting spot on the high school baseball team, which was the reason he was holed up in his room avoiding his parents to begin with.

Sol had barely had time to process it himself, even though he’d known this was coming for three months. It had been almost that long since any of his teammates had mentioned the December shower incident (now, there was a time it would have been useful to have the feeling of being watched). Only Taric, the muscular coyote who until that afternoon had been Sol’s backup at second base, made snide comments when he thought the others couldn’t hear. But the guys, especially the other wolves, had been more distant from him, hadn’t taken as much time to talk before or after practice. Sol, grateful just to be left alone after the horrible last week of December, had wrapped himself in a warm cloak of dreams about the future.

Then Mr. Zerling had called Taric up after practice that afternoon, had praised his progress, had told him he’d be starting at second base “indefinitely.” He hadn’t mentioned Sol at all. Sol could still feel the isolation, the whole team looking away from him. And Mr. Zerling was a wolf, too; he was supposed to look out for other wolves.

Sol had thought about calling Natty, but his brother was busy in college these days, between classes, football, and girls. Sol hadn’t told him about being gay, and if he told him about getting demoted, Natty would just say something like “work hard and get your spot back.”

Which was about what his dad would say. Only not as nice. And if it had stung Sol this much, with his months to prepare for it, he could only imagine how his father would react. Natty wasn’t starting, but he was already getting highly complimentary reports on his play. There was talk that he could get into a real game, rare for a college freshman. But he wasn’t eating at home every night where the family could bask in his glow. There was only Sol’s flickering light, now even dimmer. It wasn’t, Sol thought, like when the sun sets and you can finally see the moon. It was like when the sun sets and you can finally see how much the moon sucks.

He picked up his phone and typed,

I won’t have to care what my dad thinks ever again

. Then he stared at the words, erased the “ever again,” and added, “when I’m with you.” That looked better. He sent that.

And then he had to look behind himself again. There was his small bookshelf, a wall of movie posters and one small “Phantom of the Opera” poster, the disheveled bed and pile of dirty laundry: no parents, no shadow at the window. But the feeling was strong enough that Sol imagined two of his teammates hiding just outside the window, looking in when he turned. Or the Hendersons across the street, looking in his window with a telescope. Maybe all of that was happening right now, the whole neighborhood of Prospect Hill and the population of Richfield High staring through walls to see Sol tell his most intimate secrets to a ram he’d never met in person in a city four hours away.

Or maybe it was a ghost watching him. He didn’t know many people who’d died: his grandfather and his cousin, and his grandfather had died when he was five. So maybe it was his cousin’s ghost watching him. That led to Sol imagining if Percy would appear like a ghost in a horror movie with wrists dripping blood and eyes glazed with death, or if he would be like a ghost in a family movie, still the cheerful fifteen-year-old that Sol remembered from three years ago at the shore house.

The image made his fur prickle when he opened the news story again. So he hid it back under the picture of the car, and opened his phone’s web browser to a site where his study partner had set up a list of books for him to read for a school project. Might as well do homework, which as far as he was concerned the whole town could watch him do.

He’d looked at the list of book titles three times that afternoon. The problem was that the titles all looked boring, or at least, less interesting than figuring out how he was going to tell his father that he was a failure at baseball.

He read the same titles again, only—not. One new one had appeared in the list.

At least, Sol thought it was new. The title “The Confession of Jean de…” stood out to him—specifically the word “Confession,” which might as well be blinking in bold block font—so much that he was sure he would have noticed it before. He clicked on the book to find out more about it.

Under “Tags,” people had written, “Montmartre,” and “Art,” which explained why it was on the list for their project. Other tags read “Moulin Rouge” and “Dance.” And the last tag read, “Gay.”

Sol’s fingers didn’t seem to work, and the phone nearly slipped through them. He stared at the tag “Gay” and was preparing to scroll down to see the book sample when the list was obscured with a message from Carcy saying,

So when are you going to tell him?

“Aah!” Sol jumped and the phone clattered to the floor. How the hell did he get recommended a book about a gay confession when he was talking to Carcy about how to break bad news to his dad? It was too weird. He stared at the phone, lying face down, and forced himself to reach down and pick it up. Both the message and the book were still there. Don’t be an idiot, he told himself. It’s only coincidence. So he responded to the message (

Soon, I guess.

), took a breath, and opened a sample of the book.

The introduction to the translation told him that the book had been originally written in French. The translator called it “a rare and important record of politics and gay relationships in the artistic community that had become so famous, the Montmartre quarter of Lutèce at the turn of the century.”

Confession

had enjoyed a brief period of popularity in the mid-twenties for its “salacious” content, and that was enough for Sol to flick his ears back, look over his shoulder, and click “Buy.”

He paged forward and read the first paragraph of the actual story.

Dear

père

, I know that this is not what you meant when you said you wanted all of Lutèce to speak my name. From the prison window, I hear the scurrilous rumors and whispers, and it pains my heart to think that you may be hearing and believing them. They make me out to be devoid of morals, the exemplar of the

bourgeoisie

and their contempt for the peasants. They call for the return of the guillotine, for my head to be mounted at Les Halles as assurance to the lower classes that the government has their interests at heart, that it is not an attempt to re-create the monarchy. As if my head could bear all of those meanings! Dearest father, my story is a love story, a story that could be told between farmer and flower-girl, between landowner and minister. That it was told between a senator’s son and a common dancer is incidental to the heart of it, and to the tragic turn it took.

His mother called him down to dinner, and he closed the book just as he got one more message from Carcy:

just get it over with.

And the gratitude Sol felt for the ram’s support was enough to convince him to do something else he’d been thinking about for a long time. Carcy, of course, was vegetarian. He’d told Sol it wasn’t a problem that Sol ate meat, but the wolf wanted to make the sacrifice. If Carcy ate only vegetables and remained healthy, then so would he—especially if they were going to be living together that summer. Sol wanted to be used to it before he moved to Millenport.

So Sol decided he was going to get it all over with, and if his father was going to kill him for losing his baseball spot, he might as well start giving up meat tonight, too. It might take some of the heat off of the baseball news. He went down to dinner, and though he glanced behind himself once, the feeling of being watched did not follow him down into the warmth of the dining room, the rich smell of steak, the light air of classical music his mother liked to put on over dinner.

His tail stayed curled around his hip as he took his seat, but if either parent noticed, they didn’t say. He scooped a big pile of peas and carrots onto his plate, grabbed a dinner roll, and chewed the bread. He stared at the third steak, sitting alone on the serving plate in the center of the table, and waited.

His mother said something first. “Sol, take your steak before it gets cold.”

He swallowed. It would be easy here to just eat the steak, to put off becoming vegetarian until tomorrow. Only Carcy had been so helpful, and Sol had wanted to do this for weeks. Courage was easier to find when he knew his father was going to end the meal angry anyway. So he stared down at the round green peas and square orange carrots, and moved them around with his fork. “I’m—not having any.”

“What do you mean?” His father laughed. “Never seen you not hungry for steak.”

“I mean—I’m not having any, anymore. Ever.”

The room grew cold and still. His father set down his silverware. “No steak?”

“No meat.”

His mother said, softly, “Are you not feeling well?”

“I’m fine, I just—I’m not interested in eating it anymore.”

“Not interested? Not interested?” His father leaned forward, glowering. “You’re an athlete. You need your protein. Your brother recorded the second-most tackles in Richfield High history, and you know how he did it? Eating steak. How are you going to turn double plays without steak?”

Then he had to blurt it out, to deliver the other half of the bad news. The hope that his father’s rage at the combined news would be more bearable than going through this twice was fading fast. “I’m not starting anymore!”

In the silence that followed, Sol felt Natty’s absence as acutely as if his brother had only just left the previous day. The fraternal scent, the low voice and infectious laugh, those belonged in the silence that stretched on and on. Alone, Sol could not come up with anything to say that would make the news he’d just delivered go down any more smoothly. He tried to relax the tight curl of his tail against his hip, to lift his ears, to unlace his fingers from each other, anything to not look like a little cub. But the best he could manage was to pull his paws apart, shedding black fur onto the white napkin on his lap.

The faint classical music from the living room seemed to grow louder, reverberating off the stone walls. His heartbeat throbbed harder, the smell of steak pushed its way into his nose. His mouth watered, but he forced his eyes to remain on the vegetables heaped on his plate. He didn’t have to add more words, not yet. He had said all he needed to, all he could right now.