Griefwork (14 page)

Authors: James Hamilton-Paterson

The boiler room therefore had two aspects. To Leon and Felix it was an annexe of the Palm House itself which, because the public were excluded, seemed yet more private, as befitted its status as their bedroom. To other gardeners and the men who brought the coal it was more an extension of outdoors, though complete ease of access was denied them by the curator’s eccentric rules and often forbidding presence. Leon now imposed a strict rota for when the gardeners could come in and warm themselves. At all other times the boiler room door

was bolted from within, occasioning much puzzled speculation. This routine enabled Felix to slip away before the men came in. He needed merely to have a safe hiding place in case of a proper search, and this was afforded by the aborted tunnel. Having given up on their original scheme, the Palm House’s designers had ingeniously turned it to advantage by devising a way of ducting the smoke from the furnaces along it, running the flue underground for a considerable distance until it could emerge behind a spinney, disguised as the remaining tower of a ruined mediaeval keep, a triumph of nineteenth-century taste. This kept the smuts away but the sight of smoking battlements cast over that part of the Gardens something of the sinister fraudulence of a crematorium. The advantage to Felix was that the first part of the tunnel was a perfect hiding place. In the boiler room itself the huge lagged flue gathered smoke from the three furnaces, further impelled by steam as in a railway engine, before plunging through the floor next to a coal bunker. This bunker was now largely filled by an electrically driven hoist which had been the last word in modern labour saving when installed in 1927, taking the coal from outside via a hatchway and conveying it on a belt up to the hoppers which fed the furnaces. In the grimy shadow of this machine a small access door was let into the floor and led to the tunnel’s mouth.

Between them Leon and Felix had a system of warning signals which would give the boy time to drop through this panel and crouch in the hot darkness with the tube of blazing gases shuddering by his ear. These included a certain way of rattling the No Admittance door handle and, for real emergencies, dropping the word ‘stokehold’ into conversation which meant Leon and a peremptory guest were about to come through to the boiler room. As it happened, this extreme measure was seldom needed and only twice in earnest, once being when Dr Anselmus demanded to know exactly how decrepit the boilers were and to

inspect them for himself. The second time was early one morning after a heavy air raid, one of the last in the war, when a German officer and a squad of soldiers came to the Botanical Gardens looking for survivors of an American aircrew who had baled out of their stricken B-17 over the city. They made a thorough search of all the outhouses, poked among the plants in the Temperate House and then came to the Palm House, obviously dispirited. The officer quizzed Leon about parachutes. ‘The stokehold – you’ll need to see that, I presume?’ said the gardener loudly, throwing open the door with fine indifference and disclosing a neatly swept space with highly polished pipes and gauges. The officer glanced flintily around, said ‘Good work’ and gave no order to search. He and his men drove off and never returned.

With these measures working Leon tried to coax Felix out into No Admittance. At the first sounds of a visitor to the Palm House, though, the youth would scurry back into the boiler room. What combination this behaviour represented of shyness, shame and fear Leon could not judge. At any rate Felix quickly turned into a reliable boilerman, learned to operate the mechanical feeder and seemed to take pleasure in keeping the room swept and neat, polishing up copper pipes which had oxidised to a dull mahogany. Now and then he even washed clothes for both of them. When early in that final winter the coal stopped Leon would drag his lopping spoils into the yard, lock the door into the Gardens and set to work with axe and saw. It was several weeks before he could induce Felix to take a step outdoors, still longer for the boy to acquire the confidence to work there, sawing and stacking. At the least noise he would bolt indoors and cower by the entrance to his hiding place whence the gardener had to coax him, shaking. Yet under this furtive regime he appeared to be recovering well, though still unable or refusing to speak. One day, to Leon’s delight, he made himself a catapult and, sitting on the back step, began

to knock the odd thrush or sparrow out of the branches of the copper beech which partly extended over the yard. These morsels supplemented their scanty diet. The ornamental fowl had long since gone from the tarn but Leon, who as a child had learned fowling in the marshes around Flinn, had netted the shallows and sometimes snared an incautious wild mallard or oystercatcher at dusk. Quite early in the war he had cleaned out most of the Gardens’ squirrel population, trapping them by using cypress cones as bait. He then stuffed them with pine nuts and a sprig of rosemary before roasting them. They had been delicious. The occasional squirrel was still to be seen, having come in from the park across the way; but maybe the war had made them as canny as it had made people for neither he nor Felix caught any more.

Thus weeks lengthened into months and a gingerly domesticity rooted itself on the narrow frontier between the temporary and the permanent. It was as if nothing could be decided until war and winter both ended. Emergency was not subdivisible. The times were radically disrupted; no peculiar circumstance could disrupt them further. It was a way of surviving which had its own strange stability, and often at night in the boiler room’s warmth the glow of fireboxes and the sighing of the flue extended timelessly in every direction. It was then that surviving was indistinguishable from living and might happily have led nowhere else. At other times when wind and searchlights whipped through the leafless branches of the beech outside and the furnaces devoured their mixture of hoarded coal and scavenged timber, the boiler room filled with a ferocious, dense roar which made the walls shudder like those of an engine room in a ship under full way and racing towards its own destruction on an uncharted reef. Hot pipework, scorched lagging, feathers of escaping steam, the grind and clank of the automatic hopper: all were part of a power which was surely being translated into

forward motion. Leon expected to hear above it the seesaw whine of harmonics as gearwheels and transmission shaft went in and out of phase with each other. On getting up and going into the darkened House he would be half surprised to find it silent, its unmoving ironwork anchored deep in urban soil.

In the war’s final month the searchlights in the sky above the city grew more and more haywire. The gardener would stand beneath the palms and watch the beams swoop and skid as if they were unable to remember what they were looking for, no longer capable of concentrating. One by one they failed or were shot out until there was only a single beam left. Possibly its aiming gear had been damaged for instead of pointing up into the night sky it swept impotently around over the rooftops like the intermittent beam of a lighthouse. Its whizzing white passage above the Gardens distressed him.

‘Steena,’

it sang as it whanged overhead and vanished behind the trees.

‘Steena,’

it reappeared. Two nights later the House drummed to a low frequency shaking and the sky glowed vermilion. Evidently the searchlight was hit and further crippled, for although it remained alight the beam froze as it passed overhead, coming to an abrupt stop in mid-sweep so that its lower edge just caught the weathercock on the Palm House’s dome. The searing brilliance pinned the ship like a moth to the sky, leaving Leon benighted in a penumbra below. For ten endless minutes the golden galleon flared on a black sea,

‘eeeen’

,

so the gardener, staring up through the roof with tears glistening on his cheeks, covered his ears with his hands to shut out the persistent keening. Then the light went out for good and the freed ship vanished, the noise stopped, and a week later the war was over.

As a squid-cloud thins and the water transpares, the fog and mania drew apart and everyone suddenly saw with awful clarity what they had been and what they had done. There was nothing for it but to rejoice. Stygian camps emptied and people

went back to dying in ordinary untainted traffic accidents, to falling off alps in the normal course of pastime. For others the camps never did empty and they never completely came out of hiding. Leon did not triumphantly disclose the ingenious bolt-hole beneath the boiler room, nor did Felix run for cover with any less urgency. The months passed, the transients departed, the population shook down. Now was the time for citizens to re-register, for lists of voters to be re-compiled, for claims to pensions to be established, for all kinds of aberrant and abhorrent recent behaviour to be amnestied or amnesied. But Felix did not emerge, or Leon didn’t allow him to, or wordlessly they agreed to prolong their liminal predicament for reasons of their own, still subsisting on one man’s rations. Was the boy too ruined to contemplate returning to the world beyond the wall? Was grieving for a brief manhood to be assuaged indefinitely by half-life at the edge of a spurious jungle? Suppose the gardener kept warning him that gangs like those of muzzle-face still roamed the unpoliced streets, snuffling out unfinished business?

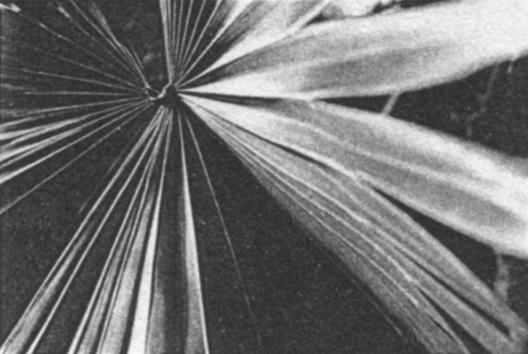

At night Leon still wandered his private jungle and sought his plants’ advice but they could tell him nothing he didn’t know. Rather, they had a habit of indulging a querulous preoccupation with their own lives which calmed him and drew him back again from the harsh and hollow-stomached transactions beyond the garden wall. Among man’s immemorial consolations is undoubtedly the company of green and growing things, no less than the melancholy comforts of scholarship. So it was that his plants had taken characters for themselves, speaking as individuals on a variety of topics. One of his favourites was

Encephalartos,

the ancient cycad which had partially appropriated the tone and manner of Professor Seneschal, a venerable Fellow of the Society and a world authority on gymnosperms. Its heavy head hung loosely in its collar and its captious asides pleased Leon as he paused to check that the soil was not too damp. ‘Turned

warmer since 1908,’ it remarked one day. ‘I put it down to the glass. Not such pretty light, this modern stuff, but it’s thicker quality. Holds the warmth better … And who might you be, young man?’

At

any

opportunity,

indeed,

Encephalartos altensteinii

seemed

prepared

to

indulge

tetchily

in

the

comforts

of

his

own

scholarship,

airing

his

theories

for

any

passer-by:

‘Wars?’ he said. ‘I’ve seen them come and go. This last has been the worst so far. All that banging and crashing at night with great flashes of light and what happens?

Draughts.

Holes in the roof and damn great draughts cutting through the House at every angle. If it hadn’t been for that new gardener’s boy they’ve brought in – what’s his name? Leon? – we’d have all of us frozen in our beds. As it was my cone became quite numb and such things are no laughing matter at my age. But he turned up the heat and mustered a gang and soon had things back to rights. The palms, of course, preserved their usual lofty disdain. Anybody here would testify that there’s not a malicious fibre in my being, but frankly I shouldn’t have minded too much if one or other of the palms had got a little smack – say a piece of steel in the head, nothing too fatal but enough to wake its ideas up a bit. A good stiff jolt to bring it back to reality, if you like.

‘You’d care to hear my theories? Bless you, I’m flattered.

Though I do say it myself I have, I think, one or two to offer. What you say is perfectly true – age does lend a certain weight, I find, to one’s opinions. There’s a fellow comes here from time to time who pokes rudely at me and fondles my parts – calls himself a professor, too, quite disgusting – Seneschal, that’s his name. Claims to be an authority on me and mine, or “gymnosperms” as he calls us – and no, Professor Seneschal, we’re not much flattered by your attention. The insolent monkey claims my noble race of cycads is

primitive.

I fear his unappealing little brain automatically equates the ancient with the unsophisticated. Like so many members of his species he sees himself as the culmination of millions of years’ evolution and thus fancies himself as

perfected.

There he stands, the great Professor Seneschal, the perfect example of his perfectly evolved species. Racial purity in person! From which position he deigns to examine my own genus and declare it imperfect. He knows quite well that cycads have survived practically unchanged for about a hundred and sixty million years longer than his own miserable species … I do beg your pardon, but you know what I mean – a rhetorical trope, merely. I’m informed that the entire evolution of the human species via the apes can now be considered as having been compressed into the last six million years or so which I’m afraid makes you by comparison a lot of Johnny-come-latelys – again, no offence. But explain if you can how, unless it’s from an innate racism, Professor Seneschal can look at a family which has survived intact all the changes and vicissitudes of a hundred and sixty million years and still see it as

primitive?

Surely it is proof of extreme evolutionary sophistication? His kind have been obliged to go from trees to trousers in a wink of time whereas we cycads have needed no such desperate measures. Does it not argue conclusively that it was we who were already perfected, having no further need of change in order to survive? None of these embarrassing

transmogrifications for us: shedding tails and shedding hair and, come to that, shedding blood. Scarcely a dignified history, if I may make so bold.