Grit (17 page)

Authors: Angela Duckworth

Here’s another example. Ever watch the Olympics? Ever listen to the commentators say things, in real time, like “Oh! That triple lutz was just a little short!” “That push-off was perfectly timed”? You sit there and wonder how these commentators can perceive such microscopic differences in the performance of one athlete versus another without watching the video playback in slow motion. I need that video playback. I am insensitive to those nuances. But an expert has the accumulated knowledge and skill to see what I, a beginner, cannot.

If you’d like to follow your passion but haven’t yet fostered one, you must begin at the beginning: discovery.

Ask yourself a few simple questions:

What do I like to think about? Where does my mind wander? What do I really care about? What matters most to me? How do I enjoy spending my time? And, in contrast, what do I find absolutely unbearable?

If you find it hard to answer these questions, try recalling your teen years, the stage of life at which vocational interests commonly sprout.

As soon as you have even a general direction in mind, you must trigger your nascent interests. Do this by going out into the world and

doing

something. To young graduates wringing their hands over what to do, I say,

Experiment! Try! You’ll certainly learn more than if you don’t!

At this early stage of exploration, here are a few relevant rules of thumb taken from Will Shortz’s essay “How to Solve the

New York Times

Crossword Puzzle”:

Begin with the answers you’re surest of and build from there.

However ill-defined your interests, there are some things you know you’d hate doing for a living, and some things that seem more promising than others. That’s a start.

Don’t be afraid to guess.

Like it or not, there’s a certain amount of trial and error inherent in the process of interest discovery. Unlike the answers to crossword puzzles, there isn’t just

one

thing you can do that might develop into a passion. There are many. You don’t have to find the “right” one, or even the “best” one—just a direction that feels good. It can also be difficult to know if something will be a good fit until you try it for a while.

Don’t be afraid to erase an answer that isn’t working out.

At some point, you may choose to write your top-level goal in indelible ink, but until you know for sure, work in pencil.

If, on the other hand, you already have a good sense of what you enjoy spending your time doing, it’s time to develop your interest. After discovery comes development.

Remember that interests must be triggered again and again and again. Find ways to make that happen. And have patience. The development of interests takes time. Keep asking questions, and let the answers to those questions lead you to more questions. Continue to dig. Seek out other people who share your interests. Sidle up to an encouraging mentor. Whatever your age, over time your role as a learner will become a more active and informed one. Over a period of years, your knowledge and expertise will grow, and along with it your confidence and curiosity to know more.

Finally, if you’ve been doing something you like for a few years and still wouldn’t quite call it a passion, see if you can deepen your interests. Since novelty is what your brain craves, you’ll be tempted to move on to something new, and that could be what makes the most sense. However, if you want to stay engaged for more than a few years in

any

endeavor, you’ll need to find a way to enjoy the nuances that only a true aficionado can appreciate. “The old in the new is what claims the attention,” said William James. “The old

with a slightly new turn.”

In sum, the directive to

follow your passion

is not bad advice. But what may be even more useful is to understand how passions are fostered in the first place.

Chapter 7

Chapter 7

PRACTICE

In one of my earliest research studies, I found that

grittier kids at the National Spelling Bee practiced more than their less gritty competitors. These extra hours of practice, in turn, explained their superior performance in final competition.

This finding made a lot of sense. As a math teacher, I’d observed a huge range in effort among my students. Some kids spent, quite literally, zero minutes a week on their homework; others studied for hours a day. Considering all the studies showing that gritty people typically stick with their commitments longer than others, it seemed like the major advantage of grit was, simply,

more time on task.

At the same time, I could think of a lot of people who’d racked up decades of experience in their jobs but nevertheless seemed to stagnate at a middling level of competence. I’m sure you can, too. Think about it. Do you know anyone who’s been doing something for a long, long time—maybe their entire professional lives—and yet the best you can say of their skill is that they’re pretty much okay and not bad enough to fire? As a colleague of mine likes to joke: some people get twenty years of experience, while others get

one

year of experience . . . twenty times in a row.

Kaizen

is Japanese for resisting the plateau of arrested development. Its literal translation is: “continuous improvement.” A while back, the idea got some traction in American business culture when it was touted as the core principle behind Japan’s spectacularly efficient manufacturing economy. After interviewing dozens and dozens of grit paragons, I can tell you that they all exude kaizen. There are no exceptions.

Likewise, in her interviews with “mega successful” people, journalist Hester Lacey has noticed that all of them demonstrate a striking desire to excel beyond their already remarkable level of expertise: “An actor might say, ‘I may never play a role perfectly, but I want to do it as well as I possibly can. And in every role, I want to bring something new. I want to develop.’ A writer might say, ‘I want every book I do to

be better than the last.’

“It’s a persistent desire to do better,” Hester explained. “It’s the opposite of being complacent. But it’s a

positive

state of mind, not a negative one. It’s not looking backward with dissatisfaction. It’s looking

forward

and wanting to grow.”

My interview research made me wonder whether grit is not just about

quantity

of time devoted to interests, but also

quality

of time. Not just

more time on task

, but also

better time on task

.

I started reading everything I could about how skills develop.

Soon enough, this led me to the doorstep of cognitive psychologist Anders Ericsson. Ericsson has spent his career studying how experts acquire world-class skills. He’s studied Olympic athletes, chess grandmasters, renowned concert pianists, prima ballerinas, PGA golfers, Scrabble champions, and expert radiologists. The list goes on.

Put it this way: Ericsson is the

world expert on world experts.

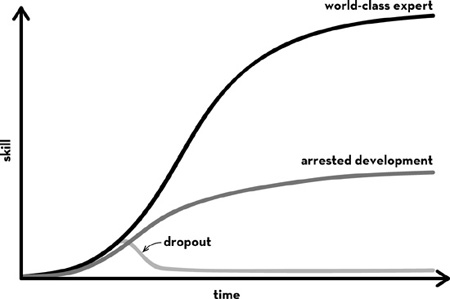

Below, I’ve drawn a graph that summarizes what Ericsson’s learned. If you track the development of internationally renowned performers,

you invariably find that their skill improves gradually over years. As they get better,

their rate of improvement slows. This turns out to be true for all of us. The more you know about your field, the slighter will be your improvement from one day to the next.

That there’s a learning curve for skill development isn’t surprising. But the timescale on which that development happens is. In one of Ericsson’s studies, the very best violinists at a German music academy accumulated about

ten thousand hours of practice over ten years before achieving elite levels of expertise. By comparison, less accomplished students accumulated about half as much practice over the same period.

Perhaps not so coincidentally, the dancer Martha Graham declared, “It takes about ten years to

make a mature dancer.” More than a century ago, psychologists studying telegraph operators observed that reaching complete fluency in Morse code was rare because of the “many years of hard apprenticeship” required. How many years? “Our evidence,” the researchers concluded, “is that it requires ten years to make a thoroughly

seasoned press dispatcher.”

If you’ve read Ericsson’s original research, you know that ten thousand hours of practice spread over ten years

is just a rough average. Some of the musicians he studied reached the high-water mark of expertise before that, and some after. But there’s a good reason why “the ten-thousand-hour rule” and “the ten-year-rule” have gone viral. They give you a visceral sense of the scale of the required investment. Not a few hours, not dozens, not scores, not hundreds. Thousands and thousands of hours of practice over years and years and years.

The really crucial insight of Ericsson’s research, though, is

not

that experts log more hours of practice. Rather, it’s that experts practice

differently

. Unlike most of us, experts are logging thousands upon thousands of hours of what Ericsson calls

deliberate practice.

I suspected Ericsson could provide answers as to why, if practice is so important, experience doesn’t always lead to excellence. So I decided to ask him about it, using myself as a prime example.

“Look, Professor Ericsson, I’ve been jogging about an hour a day, several days a week, since I was eighteen. And I’m not a second faster than I ever was. I’ve run for thousands of hours, and it doesn’t look like I’m anywhere close to making the Olympics.”

“That’s interesting,” he replied. “May I ask you a few questions?”

“Sure.”

“Do you have a specific goal for your training?”

“To be healthy? To fit into my jeans?”

“Ah, yes. But when you go for a run, do you have a target in terms of the pace you’d like to keep? Or a distance goal? In other words, is there a

specific

aspect of your running you’re trying to improve?”

“Um, no. I guess not.”

Then he asked what I thought about while I was running.

“Oh, you know, I listen to NPR. Sometimes I think about the things I need to get done that day. I might plan what to make for dinner.”

Then he verified that I wasn’t keeping track of my runs in any systematic way. No diary of my pace, or my distance, or the routes I took, my ending heart rate, or how many intervals I’d sprinted instead of jogged. Why would I need to do that? There was no variety to my routine. Every run was like the last.

“I assume you don’t have a coach?”

I laughed.

“Ah,” he purred. “I think I understand. You aren’t improving because you’re

not

doing deliberate practice.”

This is how experts practice:

First, they set a stretch goal, zeroing in on just one narrow aspect of their overall performance. Rather than focus on what they already do well, experts strive to improve specific weaknesses. They

intentionally seek out challenges they can’t yet meet. Olympic gold medal swimmer Rowdy Gaines, for example, said, “At every practice, I would try to beat myself. If my coach gave me ten 100s one day and asked me to hold 1:15, then the next day when he gave me ten 100s,

I’d try to hold 1:14.”

I

Virtuoso violist Roberto Díaz describes “working to find your Achilles’ heel—the specific aspect of the music

that needs problem solving.”

Then, with undivided attention and great effort, experts strive to reach their stretch goal. Interestingly, many choose to do so while nobody’s watching. Basketball great Kevin Durant has said, “I probably spend 70 percent of my time by myself, working on my game,

just trying to fine-tune

every single piece of my game.” Likewise, the amount of time musicians devote to practicing alone is a much better predictor of how quickly they develop than time spent practicing with other musicians.

As soon as possible, experts hungrily seek feedback on how they did. Necessarily, much of that feedback is negative. This means that experts are more interested in what they did

wrong

—so they can fix it—than what they did

right

. The active processing of this feedback is as essential as its immediacy.