Growing Up Brady: I Was a Teenage Greg, Special Collector's Edition (6 page)

Read Growing Up Brady: I Was a Teenage Greg, Special Collector's Edition Online

Authors: Barry Williams;Chris Kreski

Finally, one weekday after school, I marched into the kitchen

and launched into my. finest performance. "How can you stand in

my way?" I asked, shooting an eleven-year-old's angriest glance

toward my folks. "How can you not give your own child a chance

to fulfill his dream?"

I had stated my case, and to my surprise the folks buckled. My

figurative Berlin Wall had caved in a full twenty-four years before

the real one would. My Dad still wasn't thrilled with the idea, but I

was allowed to begin taking acting lessons.

"Don't jump right in," he advised. "Instead, why not study acting for a while and see if you really like it?" To this day, I believe he thought this idea of mine would just sort of fizzle out, allowing me

to rejoin the real world.

So where to turn? There was one neighborhood kid who had

done a few commercials and a couple of small movie scenes. His

name was Donny Carter, and when my Mom called his, we came

away with the name of my first acting coach.

Her name was Lois Auer, and she taught "scene study" courses

out of her home in Sherman Oaks. She also specialized in film and

television techniques, which made me happy, because in my electronic, baby-boomer's mind TV was the place to be. Stage actors

somehow seemed bush league. (I've since changed my tune.)

I signed up immediately. Monday night soon became acting

night and the happiest time of my week. There were ten of us in

the class, and we'd learn lines, blocking, stage directions, and

inflection. We'd also perform scenes, and talk about acting. I was in

heaven.

About six months into my lessons, I got my first big break. Mrs.

Auer told my mom and me about a school documentary that was

being cast in Hollywood. My first audition! At once I was both

thrilled and terrified. The film was called Why Johnny Can Read,

and it was one of those dull "English class" 16mm things that put

you to sleep all through grade school. Still, I was awestruck.

I auditioned with about thirty other kids-and I got a part! In

fact, not just a part, but the part: I played Johnny. My "classmates"

were each paid twenty-five dollars, but I got fifty. "Fifty bucks!" I

thought. "This is gonna be a great career!"

Buoyed by my first professional gig, I started stepping up my

study program with Mrs. Auer before too long. Now, in addition to

my beloved Monday-night classes, I began taking a one-hour pn-

vate class each Saturday. Now I could really progress. With Johnny

under my belt, and with all this studying, I thought, "I should have

my first Oscar in no time."

Well, that didn't happen; but I did get better-good enough, to

try and snag an agent. Mrs. Auer set up a meeting for me with a

woman named Toni Kelman, who owned a pretty good-sized kids'

talent agency. Once again, I was thrilled, because to me this represented a genuine step into the "business" of show business. You

really can't prepare for a meeting like this; you just have to cross

your fingers and hope something clicks.

Something did click, and the meeting went very well. Toni was

really pleasant, and while my mom waited outside with the receptionist, I fielded about a dozen of her "Let's get to know each

other" questions. Next, Toni and I read a scene from the script of a

Disney movie.

Twenty minutes later I had signed a one-year deal with her company and was off and running. To this day, I'm not sure

whether she liked my reading or if she just needed a brownhaired, blue-eyed, eleven-year-old guy in her stable of kids. Either

way, however, I was ecstatic.

Flash forward a coupla months and I'm auditioning for parts on

an average of once a week. Nothing materialized for a while; but at

just about the time I was starting to feel the first real pangs of rejection, it hit: I landed a commercial for Sears, Roebuck. It was a runof-the-mill, "Oh, gee, isn't Sears a wonderful place to shop?" kinda

thing, but it gave me my first real taste of being a kid on a union

set.

First and foremost, there's the issue of school. I was told to ask

my teachers for all the work I'd miss while away on my two-day

commercial shoot. I was also told to take my regular school books

with me to the set, where, a "production welfare worker" would

assist me with my studies.

At eleven-years-old, that sounded like a death sentence. I pictured the welfare worker as an enormous, foul-smelling, molecovered, vaguely Nazi-esque old bag, with a name like Bertha, or

Hortense, and was sure she'd turn our one-on-one student-teacher

relationship into a hellish scholastic nightmare.

Boy, was I wrong! School on the set turned out to be great. The

union's time restrictions provided that I had to accumulate three

hours of schooling per day, broken up into segments that were

each about twenty minutes long. I wasn't allowed to be on camera

for more than four hours or to work more than a ten-hour day,

with a one-hour lunch break. Even my welfare worker turned out

to be quite a babe; and with one-on-one instruction, I could knock

off my daily assignments in less than half the time they'd take back

at school.

Actually, my abbreviated school schedule did leave me with one

problem: what to do with all my leftover time.

Being on a full-blown commercial set took care of that. The

place was crammed full of so many technicians, lighting specialists,

cameramen, prop guys, and production types, that I couldn't have

been bored if I tried. I remember that everyone seemed to have

whistles and clipboards, and that they all seemed to take this commercial shooting stuff very seriously. I loved that, and made the

most of my every second of set time. I asked questions of everyone, never stopping until I became a pest. I snooped, I eavesdropped, and I just tried to soak up every bit of ambience the location had to offer.

I even had time to make friends with my co-star in the spot,

Butch Patrick. Yep, I was working with a bona fide child star"Eddie Munster" himself! I can remember pumping him for infor mation, and cockily thinking to myself, "I'm a much better actor

than he is-how come I'm not on TV?"

Well, within a year, I was on TV, having landed my first guest

shot in episodic television. I was gonna be on "Run for Your Life," a

mid-sixties drama that starred Ben Gazzara as a terminally ill hero

"trying to cram thirty years of living into his final two." I was to play

a tough New York City street kid, a real rotten little punk. My first

scene took place on an apartment stoop, and consisted of me talking to Mr. Gazzara while I lit matches and used them to burn up

some ants. I remember thinking to myself that even the guys in my

brothers' gang weren't that twisted. Still, this was to be a magical

day.

It started ridiculously early, for two reasons. Number one, I

had an eight o'clock call time at Universal Studios, which entailed

an hour-and-a-half drive even without L.A. traffic. Number two,

"Run for Your Life" was my Dad's favorite show. This time his

inherent dislike of show business melted under a wave of unbridled fandom. He volunteered to be legal guardian for a day (up

until now it had always been Mom), let his employees run the

business, and, with genuine excitement, made sure I got to the

set plenty early.

At six-fifteen A.M. my dad and I were on the lot, parked, checked

in, eating breakfast, and more than ready for my eight o'clock call.

I read the paper, dawdled over my donut and juice, and still had

time to get into makeup and wardrobe by seven-twenty.

At nine o'clock, I was called out of the studio schoolroom and

onto the Universal back lot, where we'd be shooting on one of

those nondescript could-be-anywhere make-believe streets. The

dialogue director approached and told me that he wanted to go

over my lines with me-kid actors are notoriously bad with their

lines. I assured him that I was so happy to get this job, I'd not only

learned my lines but Mr. Gazzara's as well. He was pleased, and

seemed to relax.

Nine-thirty came and went without a sign of Mr. Gazzara. Ten

o'clock and ten-thirty also passed without him. Finally, at about

five of eleven, with the director fuming, and with production types

gulping down fistfuls of Rolaids, the longest, blackest limousine I'd

ever seen pulled up and glided silently to a stop. My first thought

was that maybe the President had come to visit, but that theory

was quickly shot down when Ben Gazzara slowly and deliberately

exited his stretchmobile.

When you've only seen someone on television, it's a bit of a

shock to meet him in person. Mr. Gazzara was no exception. He

was larger than life, imposing, and had an almost regal air about

him. He was also late, but made no excuses or apologies, and I remember being impressed at how his simple request for a chair

was passed down through the pecking order of stagehands.

"Get Mr. Gazzara's chair!" yelled the biggest, fattest, most

important prop guy.

"Get Mr. Gazzara's chair!" his assistant chimed in.

"Where the fuck is Gazzara's chair?" a teamster belched.

Finally, they reached the bottom of their clan's totem pole, and

the guy at the bottom fetched the chair, running about a hundred

and fifty yards in order to gently place it within plopping distance

of Ben Gazzara's butt.

The out-of-breath lackey smiled and then watched Mr. Gazzara

light up a cigar and sit down without saying "Thank you."

I was impressed-mightily, if not favorably.

Eleven-thirty arrived, and still Mr. Gazzara wasn't ready to work.

He hadn't changed into his wardrobe, hadn't shaved, and hadn't

visited the makeup man. It goes without saying that he hadn't

come close to memorizing his lines. In fact, as I watched him look

over his script, I became convinced that he was reading it for the

first time.

High noon came. It was time for rehearsal, and an amazing shift

occurred. Even on our first walk-through of the scene, Mr. Gazzara

was tight with his lines, and really seemed to listen as I spilled out

my own. His reactions and responses seemed genuine, and affect ed me so much that I actually managed to forget I was acting. He

so totally absorbed us both in what we were doing that I forgot to

be nervous, forgot the numerous technical tasks we were performing, and nailed the scene in just two takes. This was a powerful lesson.

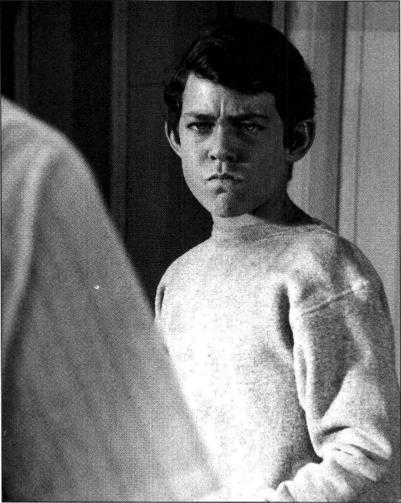

On "Run for Your

Life." (BarryWilliams)

Later, we knocked off my close-ups, and out of the comer of my

eye I saw Mr. Gazzara approach my dad and tell him something.

Later, I badgered my dad mercilessly, until he finally smiled and

confessed that Mr. Gazzara said that he thought I had done a really good job.

What a day!

nce you've appeared on one television show, future acting jobs start getting a lot easier to grab. Casting directors start recognizing your face and stop treating you

nce you've appeared on one television show, future acting jobs start getting a lot easier to grab. Casting directors start recognizing your face and stop treating you

like pond scum; the credit list on the back of your head

shot gets longer; and you find that you're no longer an outsider

but a bona fide actor, and a member of that legendary, glitzenshrouded private club, the "show-business community." Once

you're "in," things start snowballing. At least that's how it happened for me.