Hacking Happiness (18 page)

Authors: John Havens

What’s worse is that our privacy laws are utterly unprepared for this technology. Over the past few years, Facebook has used the photos posted to its site to create the world’s largest privately held database of faceprints—without

people’s permission. If you have a Facebook account and you haven’t clicked a little button on a little menu, chances are that Facebook has created a unique digital model of your face. That file can be used to identify you in any photo taken anywhere, whether or not that’s posted to Facebook. All of this is 100 percent legal under federal law.

14

Rather than try to hinder innovation, however, Franken’s primary focus is on helping consumers be informed about new technologies. He also urges companies to be proactive in having consumers choose to opt

into

a service, rather than having them automatically be signed up for a service without their knowledge where they have to opt

out

.

15

Regarding Google and Glass for this issue, Franken noted:

In the past, Google has taken a thoughtful approach to facial recognition technology. While facial recognition is on by default on Facebook, it’s opt-in on Google+. I get the impression that the Glass team is also taking the privacy concerns around facial recognition quite seriously. My biggest goal is to make sure that our privacy laws keep up with our technology. I want to make sure that all of the benefits that we see from new technology don’t come at the expense of our privacy and personal freedom.

16

The legality around issues of augmented reality are rapidly developing. Brian D. Wassom is the Social, Mobile, and Emerging Media Practice Group chair and a partner at Honigman Miller Schwartz and Cohn LLP. He has an excellent blog on AR and legal issues, and recently wrote about best practices for facial recognition privacy.

17

I interviewed him for

Hacking H(app)iness

and asked him if people would be able to block their images in the future from being recorded by Glass or other such devices.

The actual act of capturing someone’s image doesn’t necessarily infringe their publicity rights. Indeed, the creation, reproduction, and distribution of imagery is the subject matter of copyright law, and typically the person who creates the image owns it. What you do with the image—i.e., whether and how you commercially exploit it—determines whether you’re infringing on publicity rights.

That said, I fully expect publicity rights law to evolve in response to situations like this. Precisely because we don’t have a uniform rule describing what this right even is, let alone what it protects or how it can be infringed, it leaves a lot of room for creative interpretation by opportunistic lawyers. For example, although I have yet to see anyone argue this, I wouldn’t be surprised if we soon hear the argument that individuals’ facial features are a part of their identity, and that they can be exploited in various commercial ways, and so any use of unauthorized facial recognition technology is a violation of that person’s publicity rights. Mark my words—that argument is coming.

Of course, publicity rights and copyrights aren’t the only legal issues implicated by surreptitious recording. The scenarios you describe raises questions of privacy and eavesdropping, first and foremost, which also vary by state. Applying these laws will require fact-specific analysis to determine whether there was an expectation of privacy in the specific circumstances involved.

18

A number of companies are helping navigate consumers toward a time when augmented reality technology becomes ubiquitous in a privacy-protected environment. One of the best applications for AR in this regard is in the B2B, or business-to-business, environment. A leading company in this field is APX Labs, which is focused on creating AR environments for “deskless workers” using their smart glasses technology. I interviewed Robert

Gordon, the company’s chief strategy officer, to ask him more about this trend.

Deskless workers, enabled by smart glasses (augmented reality–enabled glasses), provide employees with a hands-free environment so they can be more efficient. Doctors and nurses in the medical community, workers in transportation and logistics, even people in the entertainment community are better off when utilizing hands-free, wearable computing. Biometrics can also be a component of the smart glasses experience.

19

Biometric integration provides a fascinating use of technology that APX has incorporated in the past with military technology. Outfitted with smart glasses that can utilize a technology like Cardiio to read people’s heart rates by measuring changes in the skin tones of their faces, military guards can determine if someone they’re speaking to is getting nervous.

A medical application of this same technology could allow a doctor to look around a waiting room with smart glasses and be alerted to the patient who most quickly needs attention, based on heart rate or other visual characteristics. APX has also created something called See What I See (SWIS) that lets people wearing smart glasses switch views to what another person is looking at. For health workers in the field, this means they could stare at a sick child and get a consultation from an expert physician anywhere around the world. You can see how this experience looks in a consumer environment by watching a video created using Google Glass by a teacher taking his class on a virtual field trip.

20

The Vision’s Our Own

Technology isn’t inherently good or evil. People can use a device or platform as they see fit. Augmented reality used for value-added

applications is already transforming the world for good, allowing people to easily see information they haven’t seen before in a hands-free environment. Facial recognition technology can also be utilized to great benefit when people knowingly allow their images to be tagged or utilized for medical or work purposes based on mutual consent. Soon biometric and quantified self data will also let people project a visualization of their own health to the world, perhaps publicly showing something like an icon of a sneaker to be identified as a runner in public settings.

Hacking H(app)iness will also mean we can project our emotions to the world, where augmented reality applications could essentially let our faces or clothes be perceived as a sort of mood ring to others. Or our faces could serve as the permissions portal for economic exchange, where selling your data to trusted sources could provide a new source of income. The visions of the future are limitless, and with augmented reality, we’ll get to see them like we never have before.

10

VIRTUAL CURRENCY

All the artifacts of a human being belong to physical and logical governments, and not to social networks. But the ability to move any form of asset between the virtual world and the physical world needs a commonality of understanding of identity.

1

J. P. RANGASWAMI

S

OCIAL CURRENCY

is an idea you’re already used to. In a particular clique of friends or at your local church or synagogue, you’ve earned a reputation. Perhaps it’s based on your words and personality—you’re outgoing and funny. Or perhaps your reputation is based on action—you volunteer to help a lot. Wherever you fall into that spectrum, you’ve earned a social currency based on your identity that is made up of a combination of your words and deeds.

You’re also aware of how you can redeem currency in these types of real-life social networks. For instance, say you helped someone from your synagogue carry a heavy box from inside the building to their car after a service. If you asked them to help you move a box of the same size the following week, you’d expect them to help you. If you asked them to help you move out of

your

house

, however, you’d be straining that relationship because it’s not perceived as a fair exchange of value.

A big part of Hacking H(app)iness is understanding how the worlds of digital technology, economics, and happiness intersect. Economics in the digital realm is something we’ve already touched on—you may earn a high enough Klout score, for instance, to get a Klout Perk. A brand offers you something based on your influence and the value exchange is understood. You get a coupon or a product of some kind, and the brand gets the benefit of the marketing you generate when you talk about your perk to your Twitter or Facebook audience. This is essentially paid advertising, where the brand reaches your audience in exchange for a product.

Economics and happiness in the digital realm intersect with regard to your data. As consumers and citizens we’re being measured in ways we don’t fully understand, but the portraits of who we are (our digital/virtual identities) are being projected in public and private realms. If we don’t understand or control our identities, how can we measure or even increase happiness? To fully leverage information about our happiness and well-being generated from quantified self devices or other inputs, we need to own our data.

But what if you could sell your data directly to brands at a profit? By eliminating data brokers, people could establish their own virtual storefronts for their own data to sell as they’d like. This would provide a form of virtual currency exchange, as the online market would determine what your data was worth.

Federico Zannier, a New York University graduate student, decided to pursue this idea by selling his data via a Kickstarter campaign called A Bite of Me. People who participated in his campaign bought increments of Zennier’s data beginning at two dollars a day. Zannier utilized a number of tools to gather data for the project while also educating users. Like marketers, Zannier used tools that tracked his Web traffic and activities, and software that tracked his GPS location. But as Sarah Kessler explains in her

Fast Company

article “What If We Thought More Often About Being

Tracked Online? Man Stalks Himself to Find Out,” it was the act of selling his data via Kickstarter that made Zannier’s project truly unique. First of all, it made people realize how thoroughly our actions are being measured and evaluated via our online and mobile behavior. Second, as Kessler notes, the project poses a question: If data is valuable to companies, why shouldn’t the people who create that data be able to sell it?

2

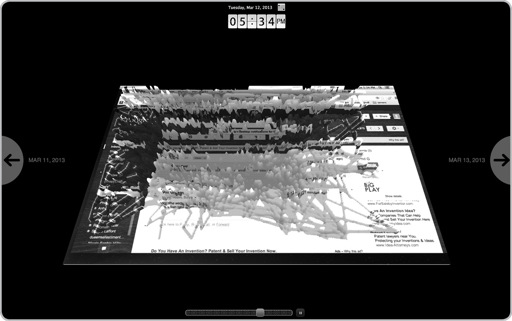

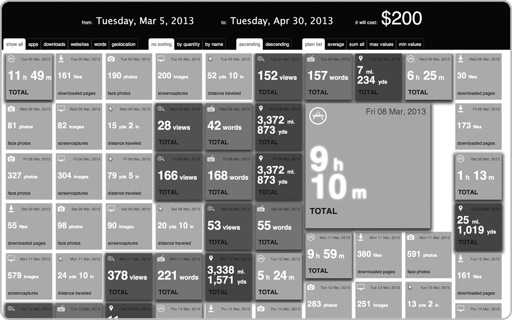

I bought a week’s worth of his data, paying five dollars, which included around five hundred websites Zannier visited, four thousand screenshots he took, four thousand webcam images, a recording of his mouse pointer movements, his GPS location, and an application log of 4,200 lines of text. Here are some visual samples of his data:

Do I know what an advertiser would pay for his data for this same time frame? Nope. I am fairly sure if I did the same thing, an advertiser would pay a lot less for

my

data, as I’m forty-four years old and have two kids and a mortgage. You don’t need a calculator to figure out that means I have less disposable income than a young, savvy New York graduate student.