Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love (23 page)

Read Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love Online

Authors: Myron Uhlberg

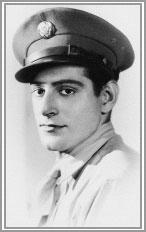

Harry (above) and my mother’s youngest brother, Milton (below)

Harry, another of my mother’s brothers, was a sailor on a battleship somewhere in the Pacific Ocean. He sent me a sailor’s hat. It was spanking white and broken in quite nicely, with creases in all the right places, and I liked to wear it tilted over one eye at a rakish angle. With my sailor hat on my head, I marched around our apartment, walking splayfooted as I imagined my uncle did when manning the deck at the height of a storm in the Pacific, the waves crashing over the bow, roller upon roller.

Our apartment was small. I was constantly underfoot. And as my mother liked to wash and wax the kitchen floor every day—hourly, it seemed to me—she often chased me out of the apartment and into our third-floor hallway. My brother, however, had to remain inside with her, ever close, where she could keep an eye on him.

Soon the older kids in the building, all wearing scraps of a uniform—an odd hat here, a cracked leather belt there—joined me. We stomped up and down the marble-floored hallways and clattered up and down the metal stairways, singing:

“You’re in the Army now. You’re not behind the plow. You’ll never get rich by digging a ditch. You’re in the Army now.”

Our combined voices echoed through the halls and up and down the stairwells, until angry neighbors flung open the door of every apartment and shouted at us to

shut up!

, threatening to give chase if we didn’t.

To escape the enemy, we ran to the elevator and took it to the basement. As soon as the door opened and we tumbled out, we went running through the musty darkness alongside the dim chicken-wire storage rooms and the ever-glowing open mouth of the malevolent monster of a furnace. Bursting out the cellar door, we exited into the alley, once again safe to march and fight another day.

Exhausted but exhilarated, I would retreat to our apartment, where I would let Irwin wear my military equipment, while I tutored him in marching and singing military songs. This attention I paid to my brother pleased my mother, but she still drew the line at our marching on her newly waxed kitchen floor.

My longing for a uniform—and for some kind of outlet for my youthful energies—caught my father’s attention. As the Allies took Paris in August, my father came home holding a large, long box under his arm. Placing it with great authority in my hands, he commanded me to open it. Inside the box was a brand-new, sharply creased Boy Scout uniform, complete with regulation belt, knee-high socks, pleated scarf, and lanyard.

“This is a uniform for you. And your black Thom McAn shoes,” he signed, “with a good shine on them, will be perfect.”

I did not know a single kid in all of Brooklyn who was a Boy Scout.

There must be a reason no one is in the Scouts,

I thought as I held the box in my arms.

While I stood there, my father marched (there is no other word for it) into his bedroom and returned, still marching, with a silver-framed picture of himself, taken when he was a boy. The picture showed him dressed in his deaf-school military uniform, peaked cap and all. The photo was dated 1912. He looked exactly like one of the Union drummer boys in the Civil War pictures that were in our history books at school.

My father at Fanwood School for the Deaf, 1912

“You’re just the same as I was when I was your age,” he signed to me, emphasizing the sign for

same.

“I was easily bored, just like you. Left to myself, I would get into trouble of one kind or another. After all, I had no one to talk to. No one in my family knew sign. The kids on my block did not know sign. I was on my own. However, that all changed when I went to Fanwood, my deaf residential school. It was patterned after a military academy and was run like a miniature version of West Point. We wore uniforms and marched constantly: from class to class, from class to dining hall, from dining hall to gymnasium, from gymnasium to playing fields, and virtually from pisspot to pisspot.”

I had to ask him to explain his sign for

pisspot.

His two hands pointed downward, one in front of the other, pivoting at the wrists. I understood immediately. Then they moved back and forth—

marching

—his dangling fingers indicating the rows upon rows of marchers, stepping out in unison and in perfect harmony. Watching his hands, I was hypnotized; I could see my father and his schoolmates, rank upon rank, marching, marching, marching.

“You can’t imagine what a good marcher I became, although at the time I saw no practical use in the Bronx for this odd skill. Unless you count marching in my dreams as a skill.” He smiled at the thought.

And then like a cloudburst, my father’s face suddenly darkened. “Later, I came to understand why the school placed so much emphasis on us deaf kids being disciplined. Our hearing teachers thought that being deaf, we would be uncontrollable if left to ourselves, like animals in the wild. So, their thinking went, we had to be disciplined—we had to be taught, basically, to obey orders. But that’s another story.”

Taking me by the hand, we

marched

into my bedroom, where my father watched as I put on my spanking-new, sharply creased Boy Scout uniform.

Now what?

I wondered.

As if reading my mind, my father signed, “The Boy Scouts are not big on marching. But discipline and obedience are important. And you could use a healthy dose of both. But don’t worry, it’s not all about that. You’ll learn things as well. And for every new subject you master, you’ll get a merit badge. I’ll help you with that.”

The first meeting was to be held in the basement of our scout leader’s home, on the other side of Seth Low Park. Although it was just four blocks away, it might as well have been on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. I was not in the habit of wandering far from my block.

For my first meeting my father accompanied me, waiting outside until it ended after a couple of hours. I had never been so bored in my life. All we did at that first den meeting was repeat, over and over again, the Boy Scout oath.

Subsequent meetings seemed to be no improvement. If anything they were worse because my father ceased to accompany me, which meant that every time I ventured out in my ridiculously elaborate blue uniform, the bullies in the neighborhood chased after me, making fun of me. But my father remained enthusiastic. He’d consulted the “merit badge” section of the Boy Scout manual and was determined that I should earn one.

So one night after supper I found myself at the kitchen table, sorting through about a million assorted postage stamps, spilled from a plastic bag that my father had bought in a philatelic shop in the city. Staring up at me were assorted strange-looking faces, covered in various styles of facial hair—spade whiskers, waxy curled mustaches, even muttonchops—and an equally exotic assortment of strange beasts, all printed in brilliant colors.

In the exact middle of the table sat a new stamp book, open to the first, blank page, which seemed to dare me to fill it, so as to one day earn my very first merit badge: “Stamp Collecting. MB [merit badge] No. 108.”

My father put on his printer’s visor, shielding his eyes from the kitchen light, and delicately selected a single stamp from the jumbled pile. Holding it carefully by the edge, he placed it in front of me, handed me a shovel-headed pair of tweezers and a hinge, and instructed me to mount the stamp in the appropriate-size box on the blank page of the stamp album.

I grasped the stamp with the sharp tweezers and pressed it onto the glued hinge—and in so doing, tore the whiskered face in half.

My father groaned. “Gently, softly.” My father’s hands gently, softly, and ever so slowly squeezed an invisible object.

I tried again. This effort produced an interesting crease in the otherwise curled horns of an antelope, creating the illusion that they grew out of the poor animal’s tail.

In desperation, not waiting for my father’s comment, I grabbed yet another of the pristine colored bits of paper and gently, softly, placed it squarely on the hinge in the dead center of a box. I paused, letting the glue dry and so adhere to page and stamp.

Satisfied that I had at last brought the process to a successful conclusion, I gently, softly, removed the tweezers—taking the entire perimeter of the stamp, now glued to the tweezers, along with it, and leaving the heart of the stamp defiantly glued to the hinge on the page.

Looking up, I saw my father’s eyes cross, and his lips compress in anguish. His expressive hands lay silenced on top of his head. He had nothing to say.

I dug into that pile of stamps frantically, desperately, time and time again, with pretty much the same results.

Finally my father stilled my hands in his. “I have another idea,” he signed.

The following week he brought home a set of X-Acto knife carving tools. Three knives were housed in individual black cushioned recesses in the bottom of a blond wood case. An assortment of extremely sharp-looking blades, of various sizes and shapes, were held in place by felt loops on the inside of the brass-hinged lid. The lid had an ornate brass latch that fit precisely into a matching brass catch. The whole affair was a wonder to my eyes. It was magnificent. But what in the world was it for? I wondered.

“MB No. 118. Wood Carving,” my father signed to me, with an optimism I was sure was misguided.

That evening we sat, my father, brother, and I, where we always sat when there was a project at hand—at the kitchen table. And as usual my mother was doing the dinner dishes, her back turned to us, but a definite smile on her face; a smile that threatened, I thought, to break into a belly laugh.

The X-Acto knife set sat squarely in the middle of the table, on a sheet of the day’s newspaper. Alongside the open case were three bars of Ivory soap.

“We’ll break in these knives by carving the bars of soap. That way we won’t dull the blades, and you’ll get practice in carving.”

That made sense to me, and picking up one of the knives, I proceeded to slice a bar of soap neatly in two, along with the web of skin between my thumb and forefinger.

My brother, who had been eyeing the box of blades enviously, left the table in a precipitous rush at the sight of the blood spurting from my hand. He was always complaining to my father that I always got new things first, never shared them, and passed them on to him only when they got old and worn or even broken. But this time he lost interest in my latest acquisition almost immediately.

Once the flow of blood was stemmed and the cut was bandaged, we tried again.

“Gently, softly,” my father signed. I was frankly getting tired of these signs.

But slowly, gently, softly, I learned to use the knives and succeeded in carving out of the soft, yielding soap an approximation of an antelope. Sure, it looked as if its horns were growing out of its tail—actually, it looked remarkably like the stamp I had mangled. But what the heck, it wasn’t half bad.

I can do this,

I thought.

“Practice,” my father signed. I did. Every afternoon I carved an animal from a bar of soap, some strictly from my imagination, and every evening I would display the result to my mother and father, as my brother stared skeptically at my latest effort.

“WONDERFUL,” my mother would sign expansively, exploding her open hands from the sides of her face in admiration.

“Practice,” my father’s more subdued sign suggested. I did. In time the bathroom was filled to overflowing with grotesque soap animals of every imaginable description. We washed with elephants with one ear missing. My brother and I bathed with mice and rats missing tails and ears. My father shaved with short-necked giraffes. And my mother did the dishes with soap nightmares that no one, not even myself, could explain. However, the scabs that formed on both of my hands, the result of countless nicks and cuts, were easily identifiable.