Read Hank Reinhardt's Book of Knives: A Practical and Illustrated Guide to Knife Fighting Online

Authors: Hank Reinhardt

Hank Reinhardt's Book of Knives: A Practical and Illustrated Guide to Knife Fighting (7 page)

It’s more common to think of these elements as “tactical terrain advantage,” but I think you gain a psychological advantage by simply regarding them as a weapon. The term “weapon” has a less pedantic ring than “tactical terrain advantage,” and it’s nicely suggestive. Remember: your frame of mind is always your chief weapon.

Stance is also important because, from there, you will move into your attacks as well as your defense. It should be remembered that when you’re out of range, your stance doesn’t matter. Hell, you can hold your knife in your teeth, if your opponent can’t reach you with his. Just be able to get the damned thing back in your hand when he starts to close in on you.

With large knives, a lot of people advocate a modified fencing stance.

All edged weapons are not equal. Though popular, this modified fencing stance is not best for knives.

The theory here seems to be that since swords and knives are both edged weapons, why then, sauce for the goose tastes just as good on a gander. Well, I can tell you a goose can have a gamier taste and require a more pungent sauce.

The difference between swords and knives is this: a sword is both an offensive and defensive weapon, whereas a knife is not. The attack is delivered with the sword and it is defended against by the sword.

But a knife, regardless of size, is an offensive weapon. It has defensive capabilities, but they are highly limited and, because of length, do not include the practical capability of blocking another knife.

Let me illustrate this with an experiment. Roll up two sections of newspaper. Have a friend take one of them and use it as if he were cutting and thrusting, while you try to block with the other. As long as he makes straightforward moves, you’ll be all right; in fact, if you’re an experienced fencer, you may find yourself doing quite well.

But the moment your opponent starts to fake and cut, or merely attack and let the blade drop or rise high, you’re lost. The two blades are simply too short to guarantee you’ll be able to make contact consistently enough to parry or block.

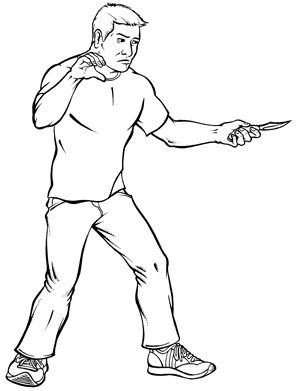

The stance that gives the best protection while offering the greatest latitude in your attack is a modified boxing stance—that, of a left hand boxer with a right hand lead.

A modified boxing stance gives better protection plus offers leeway for different attacks.

Right leg and arm are slightly forward. The body is in a slight crouch. The left arm is back, and I would suggest you keep your left hand closed tightly in a fist. It’s threatening, can be used to punch with, and the fist can give speed and authority to a blocking movement.

Keep both arms close to the body, elbows in. Stand face on to your opponent. This offers pretty good protection for the vital areas. Arms protect the sides, the forearms and hands guard the face, and the elbows give a reasonable amount of protection to the midsection and chest.

From this position, you can also launch an attack in almost any direction. You can slash from either side, give a full fencer’s lunge, and even switch hands quickly and easily.

It’s useful to teach yourself to switch the knife from one hand to the other. It can allow you to attack quickly from a totally unexpected quarter and it can let you set up distracting movements. If you switch hands and attack, and don’t finish the fight, you can fake a hand switch and attack with the primary. But switching hands is tricky and there are a lot of opportunities to screw up attempting it.

Once more, I can best show you what I mean by going back nostalgically to those glorious misspent days of my youth. I’m thinking particularly of one summer night in the park when I and my friends were engaged in our usual occupations of girl-watching and wise-assing. A commotion started suddenly at the entrance to the pavilion and sorta flowed in—like water into a gutter.

Someone none of us knew had made an entrance and was doing his best to give the impression he was as bad as they come. He walked straight down the path, not moving aside for anyone or anything. He bumped men, women, little kids, and girls. The whole world just had to know how tough he was.

There was a guy in the park we called “Smokey Stover” after a comic strip character. He was a few years older than my friends and me, and he was mean all the way through. Well, Tall Tough Stranger bumped right into Smokey. Smokey never batted an eye, just slapped the boy with his open hand.

Tall Tough Stranger jumps back and starts talking the Bad Talk, fumbles in his pocket and, with a very loud click, pops open one of those damn Italian switchblades. Smokey just stood there. He’d already thumbed his knife open and had it dangling at his side.

It’s a good bet TTS had seen

Rebel Without a Cause

, because as he advanced in a low crouch, arms real wide, he tossed his knife from hand to hand.

Rebel without a chance.

I don’t mean he switched his knife from hand to hand. I mean he

tossed

it so that it traveled a couple of feet through the air. He was good. He must have spent hours in front of the mirror, practicing the trick. Too bad he didn’t take fifteen minutes thinking about it.

Smokey leaped forward and he looked like he belonged in a movie himself. It was a beautiful, long, low lunge worthy of Errol Flynn or Stewart Granger. He was tall and skinny with a lot of reach anyway. His knife was aimed right at the eye of TTS. TTS made a beautiful leap straight back.

The problem was, he was right in the middle of one of those impressively practiced knife tosses of his. When he jumped back to avoid the point of Smokey’s weapon, he left his hanging in midair.

Smokey kicked the knife away and TTS looked upset at that. It was nothing, however, compared with how upset he was about to look. I guess he had reason.

Looking back, the whole thing seems damned stupid for the simple reason that it was. First of all, no one went looking for a fight in the park. They happened there all the time, but the object was to avoid them without being stepped on. King Kong walked softly there. So TTS wasn’t real bright to push into things there to begin with.

Secondly, he didn’t seem to understand that knives are real. They make real cuts and the blood you bleed is real, and the pain is damned real.

And last, why hadn’t he realized that switching a knife from hand to hand is one thing—but sacrificing control of your weapon is something else altogether.

He also forgot—or never figured out—the cardinal rule of survival. Always remember: you never know who the other guy is until you fight him. And by that time it might be too late to do anything about it.

Smokey Stover was the stuff of legends in our little circle. Everyone knew he carried a knife and would rather cut you than eat. I never heard of him being in a fistfight. If you got into a fight with him you had to cut him first, or maybe hit him with a baseball bat. Otherwise you’d get cut.

PRIMARY TARGETS

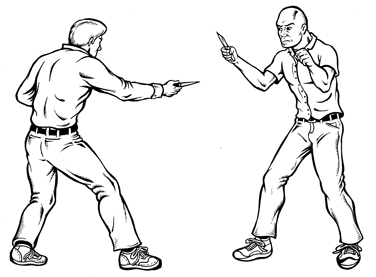

When forced into a position of having to use a knife against a similarly armed opponent, your primary targets should be the knife hand and arm.

When facing another knife-wielder, go for the knife hand and arm.

Of the two, the arm is the better target. It is larger, providing more area to cut, and damage there can affect the ability of your opponent to hold his knife. Don’t pass up the hand, but try for the arm.

Most knife fighters will assume a stance that protects the body, neck, and face by covering them with the arms and moving them slightly out of your range. If you can land a blow to the head, by all means do so, especially if the blood will run into your opponent’s eyes. Scalp wounds bleed copiously, far in excess of the actual damage done, and it’s hard to fight when a heavy stream of your own blood is obstructing your vision.

Either hand is a good target. With a big knife, you can go so far as to lop off fingers given the opportunity. But a small knife can still cut deeply, especially if you remember to angle the cut. A few such wounds and just about anyone will be ready to call it a day.

In any one-on-one situation, remember the words of George Silver: “That there be no wards or grips, and to use continual motion.”

There are no specific parries that can be made in a knife fight because there are no specific cuts or stabs to watch for. Since the knife hand and arm are targets, it follows that they should be moving because a moving target is harder to hit. Bobbing and weaving the whole body might help a little, but above all it is the arms that should be moving when you are in range of your opponent’s knife. When out of range, it doesn’t matter. You can rest, so long as you don’t go to sleep. But once you’re in range of his knife, you have to keep moving.

The ability to judge distance accurately is critical. When your opponent attacks, you have to be able to tell if his knife will land or fall short a few inches. If he lunges, will his blade reach you? In an actual battle, you’ll find yourself constantly assessing such things.

Staying out of range.

The idea is to stay out of range until you are ready to attack, or receive his attack and counter. Counter-cutting can be very deadly. If an attack is made and fails to hit the mark, the attacker has put himself in his opponent’s reach and is vulnerable until he pulls back. If the opponent moves at the right moment, and with a good counter, the fight is over then and there.