Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (33 page)

Nowhere has the transformational power of redistribution been expressed more vividly than in the heart of New York City. When she was hired in 2007, the city’s charismatic new transportation commissioner, Janette Sadik-Khan, mused that she was now the city’s largest real estate developer. It was true. The Department of Transportation controlled six thousand miles of streets, more than a quarter of New York City’s land base.

For as long as anyone could remember, the city’s transportation commissioners had focused on moving cars as fast as possible. That narrow approach was now out the window. Sadik-Khan insisted that she was going to put that real estate—some of the most valuable in the world—to its highest and best use, which did not necessarily mean moving cars.

She began with a reappraisal of the value of city streets, inviting Jan Gehl to study the movement of people in New York using the methods he had developed in Copenhagen. Gehl and his team found that despite the city’s preoccupation with vehicle traffic, walkers were much worse off than drivers. Congestion was far more acute on New York sidewalks than out in traffic lanes. They were clogged enough to generate collisions and conflict around bus stops and street furniture, to push people into the path of cars, and to discourage many from walking entirely.

*

Tellingly, only one in ten pedestrians they counted were children or seniors, even though they made up nearly a third of the population.

This unfair state of affairs had its epicenter at Times Square, where pedestrians outnumbered cars by more than four to one yet were crammed into about a tenth of the space that cars got. More than 350,000 pedestrians passed through Times Square every day, from office workers emerging from two of the city’s busiest subway entrances to befuddled tourists dragging roller suitcases from curb to curb to curb. If you wanted to get run over, Times Square was one of the best places in the city for it.

Ironically, reserving almost all of Times Square for automobiles did not necessarily benefit drivers. The problem lay in the odd geometry created by Broadway’s diagonal jig across the Manhattan grid. Broadway and Seventh Avenue crisscross between Forty-third and Forty-seventh streets, creating a four-block bow tie of conflict. The complex crossings were causing brutally long red-light delays. Vehicle speeds had slowed to four miles per hour.

The square epitomized the futility of trying to solve mobility issues by simply devoting more road space to traffic. A solution had evaded planners for decades. Sadik-Khan addressed it by employing the Copenhagen method: conduct a temporary experiment to see what spatial redistribution might accomplish. On Memorial Day weekend in 2009, Sadik-Khan joined city street crews as they rolled traffic barrels into place like so many orange beer kegs, blocking the flow of cars along five blocks of Broadway in and around Times Square.

“I will never forget it,” she told me later. “Have you ever seen

Star Trek

? The way people materialize in the ship’s transporter? It was like that. People just appeared! They just poured out into the space we created.”

Sadik-Khan’s ambitious redistribution of New York City’s street real estate—which included painted bike lanes as well as cycle routes separated from traffic by planters and parked cars, bus-only lanes, and public plazas—precipitated some angry backlash. (I will address the psychology of these power struggles in the following chapter.) But there is no denying that by providing for more complexity and different means of moving through Midtown, the streets became simultaneously more efficient, more fair, more healthy, and even more fun. The benefits extended to drivers. A year after the change, the Department of Transportation observed that traffic was actually moving faster on most streets near Broadway. Accidents were down. Injuries to drivers, passengers, and pedestrians plummeted.

The experiment also produced the remarkable dividend that comes when places slow down: more public life.

Before the change, there were two ways of experiencing Times Square. You either sat in a car and cursed the traffic and pedestrians in your way, or you shuffled along an overburdened sidewalk with one hand on your wallet. Times Square lived large in the global imagination, but when you got there, it revealed itself as an obstacle rather than a destination. Its sidewalks were so crowded they were a perfect place to experience Milgram’s theory of overload: you coped by either ignoring the people around you or doing subtle battle with them. If you were a tourist, once you got the requisite snapshot, you escaped as fast as the crowd would allow. New Yorkers who could avoid it did so completely.

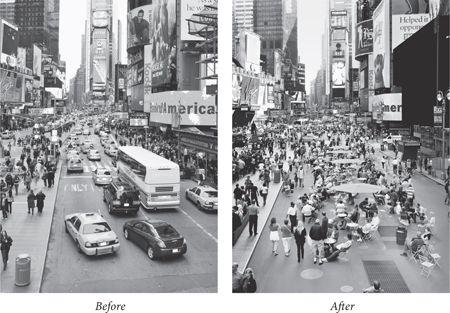

Doing It in the Road

Immediately after the barricades went up, people claimed the once-forbidden road space in Times Square.

(New York City Department of Transportation)

But after the barriers went up, the place started to breathe. I visited Times Square periodically over the next two years and did not fully grasp its new generosity until I arrived with my eighty-four-year-old mother on a blustery September afternoon in 2011, the year after the mayor had declared the changes permanent. The walk through Midtown’s jostling crowds had not been easy. My mother white-knuckled her cane, and I held her close. But as we crossed Forty-seventh Street, the aggressive crowds suddenly eased. She let go of my hand. I paused on the glowing red staircase that does double duty as a roof for the TKTS theater-ticket booth and seating for the public theater of Times Square. Before I knew it, she had stepped down over the curb onto the surface of Broadway. She moved slowly and determinedly south among the groves of chairs that the Times Square Alliance had scattered on the asphalt. She paused near the bronze statue of George M. Cohan, made a tripod with her cane, and turned her gaze upward. Her face was lit with the flash and sparkle of the billboard light show. Waves of people moved around her, but they gave her wide berth. There was room to spare. This was her own Robert Judge moment. She was free in the city, at least for a couple of blocks.

10. Who Is the City For?

The right to the city cannot be conceived of as a simple visiting right or as a return to traditional cities. It can only be formulated as a transformed and renewed right to urban life.

—Henri Lefebvre, 1968

It would be wonderful if the shapes of our cities maximized utility for everyone. It would be wonderful if city builders were guided purely by an enlightened calculus of utility. But this is not how the world works. Urban spaces and systems do not merely reflect altruistic attempts to solve the complex problem of people living close together, and they are more than an embodiment of the creative tension between competing ideas. They are shaped by struggles between competing groups of people. They apportion the benefits of urban life. They express who has power and who does not. In so doing, they shape the mind and the soul of the city.

Sometimes a self-evident truth does not become salient until you see it written in bold text across the most extreme landscape. This is what I learned in Colombia.

Jaime, my host in Bogotá, was a cautious man from the middle class. His timidity had calcified on the afternoon when a gang of paramilitaries fired a rocket at the office tower where he worked as a television editor. The projectile missed its mark, but Jaime’s trust in his fellow citizens never quite recovered. He ordered me not to walk the streets of Bogotá alone. He warned me never to wander at night. Most of all, he forbade me from visiting the ragged slums on the southern fringes of the city, where civil war refugees settled on the plains between the meandering Bogotá and Tunjuelo rivers. Well-to-do Bogotans imagined that the slums were a nightmare collage of rape, muggings, and murder. But these new neighborhoods were the landscape on which a radical new urban philosophy had been inscribed onto the city over the previous decade. So I snuck out of the apartment early one morning while Jaime was still snoring in his room, crept past the night guard, and walked down through pools of jaundiced lamplight to Avenida Caracas.

I pushed through a turnstile and stepped inside a sleek pavillion of polished aluminum and glass. Polite messages ran silently across an LED screen like quotes on the NASDAQ stock ticker. Four sets of glass doors slid open in unison. I stepped through into an immaculate carriage and took a seat. With a growl, the vehicle eased forward, gaining speed until it was whooshing down the smooth guideway.

It reminded me of the Copenhagen subway—superfast, superclean, superefficient—only instead of rumbling blindly beneath the earth, we could watch the purple glow of dawn over the silhouette of the Andes. And this was no train or high-tech people mover. It was a bus. A bus—just the low-status ride that North Americans love to hate. But the TransMilenio, as Enrique Peñalosa dubbed this bus system, had turned the transit experience upside down. Based on a rapid bus model pioneered in Curitiba, Brazil, the TransMilenio had appropriated the best space on the city’s great

avenidas

, leaving car drivers, taxis, and minibuses to fight for the scraps. This is exactly what American streetcar companies had begged for during the car invasion of the 1920s, and which most cities have not seen for decades: a system that aggressively favors those who share space, discourages those who try to grab more than their share, and saves taxpayers from having to fork out for expensive subway lines or new freeways. For a small fraction of the construction cost, the system moves more people per hour than many urban rail-transit systems. Transit fanatics come from around the world to take this ride.

With its lipstick-red coat and gleaming stations, the TransMilenio felt downright sexy. That’s right: the best way to get to one of the poorest neighborhoods in the hemisphere is to take the sexy bus. We covered about ten miles in twenty minutes. Just as the sun was cresting the Andes, we rolled into a grand airportlike complex at the end of the line. More glass curtains and polished marble. Streams of scruffy commuters pedaled along bike paths into a spacious bicycle-storage hall guarded by armed valets. This was Portal de Las Américas, a transit hub appointed with the flair of a bullet-train station.

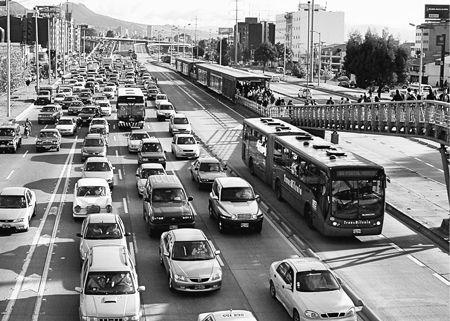

The Sexy Bus

Bogotá’s TransMilenio bus system claimed the best road space in the city from private automobiles and used high-quality finishes in its stations. The intent was not just to cut travel times but also to boost the status of public transit riders.

(Courtesy of the City of Bogotá)

I jumped in a pedicab and asked the kid at the handlebars to take me to the heart of the barrio misnamed El Paraíso—Paradise.

“Yes, sir,” he said in Spanish. “But you must hide your camera.” Then he jerked the rusty tricycle around and headed against the current of work-bound cyclists, his breath leaving a contrail in the cold morning air. El Paraíso resembled any other South American aspirational slum: prickly stands of rusted rebar poked from half-built cinder-block walls, monuments to the mansions people imagined completing in their future. Feral dogs chased plastic bags along dirt streets.

But partway along what turned out to be a roundabout journey, the cinder-block walls parted to reveal a monumental white edifice standing in a grassy park. “El Tintal,” the kid said as we wheeled past. With its great round windows and tilted skylights, the building looked like a space portal. In fact, it had spent most of its life as a garbage-processing plant before being retrofitted into a library by Daniel Bermúdez, one of the country’s most respected architects. The ramp once used by dump trucks was now a grand elevated entranceway. “Who on earth would come all this way, and to this neighborhood, to peruse the stacks?” I wondered aloud, rather stupidly.

“My mother,” said the kid. “And me.”

The boulevard we found slicing through the middle of Paradise was just as surprising. Usually, the first thing that poor cities do to improve dirt roads is to lay a strip of asphalt down the middle so cars can barrel through. This was different. A wide runway of concrete and tile ran down the middle, but it had been raised knee-high to prevent cars from gaining access. The result: a grand promenade reserved exclusively for pedestrians and cyclists. Now and then a car would rumble through the moonscape of potholes and rubble along the edge of the road.