Heat (16 page)

Authors: Bill Streever

Faraday, between ignitions, echoed Lavoisier, explaining that food is a form of fuel, that “we may thus look upon the food as the fuel,” and that humans, in eating, produce “precisely the same result in kind as we have seen in the case of the candle.” It was a realization that he considered “beautiful and striking.”

“We consume food,” he wrote. “The food goes through that strange set of vessels and organs within us, and is brought into various parts of the system, into the digestive parts especially; and alternately the portion which is so changed is carried through our lungs by one set of vessels, while the air that we inhale and exhale is drawn into and thrown out of the lungs by another set of vessels, so that the air and the food come close together, separated only by an exceedingly thin surface; the air can thus act upon the blood by this process, producing precisely the same results in kind as we have seen in the case of the candle.”

He extended the explanation to other species: “All the warm-blooded animals get their warmth in this way.”

The heat of the warm-blooded mammal is the heat of the sun. Grass intercepts a bit of energy from the sun. It uses that energy to combine carbon dioxide and water to form a molecule of sugar, a carbohydrate. That molecule holds the essence of sunlight, ready to discharge it later. That sugar, that carbohydrate, has just become a stick of metabolic firewood.

A hen eats the grain from that grass, imbibing its stockpile of metabolic firewood. The hen lays an egg. Hérve This boils the egg with precision and eats it. From grass to This is a chain of who ate whom, a chain of burned firewood, a chain of reactions that are at their most basic no different from those of a burning candle or a camp fire. Carbon combines with oxygen to release energy and carbon dioxide.

When eating eggs, the distance between Hérve This’s mouth and the sunbeam is a distance of two links. But in these two links, the vast majority of the sun’s energy disappears, wasted to the inefficiencies of life, undigested or lost as waste heat in the chemical reactions of metabolism. Each link represents an 80 or 90 percent loss. The hen recovers only 10 percent of the energy in the grass seed, and This recovers only 10 percent of the energy in the egg, receiving only a single percentage point of the energy originally donated by the sun.

But said another way, Hérve This, in consuming an egg, dines on the sun.

John Tyndall, at the end of his 532-page

Heat: A Mode of Motion

, included a few hundred words written by Frederick Boyle. “Among some of the Dyak tribes,” wrote Boyle, “there is a manner of striking fire most extraordinary.” Boyle describes the Dyaks using bamboo to strike a fire, not by friction but by compression. A bamboo tube is somehow thrust down over a block containing tinder. The sudden heat of compression lights the tinder, like the downward stroke of the piston in a diesel engine igniting its fuel. I find the description difficult to follow and unbelievable. “I must observe that we never saw this singular method in use,” Boyle wrote, “though the officers of the Rajah seemed acquainted with it.”

Through the mail, I order a fire piston. It is a two-part device, six inches long, distinctly phallic in shape, made from the horn of a water buffalo. One part is the cylinder, and the other part is the piston itself. The piston slides into the cylinder. At the tip of the cylinder is a chamber. The chamber holds a sliver of tinder not much bigger than the head of a match. The instructions: “Push or strike the piston with your palm, driving it forcefully into the cylinder.”

The fire piston goes into my pack, along with two kinds of commercially available tinder made from fibers impregnated with wax or oil, and a brand-new disposable lighter. I also pack a small sheet of thin cotton that has been heated to drive away its moisture and most of the oxygen and hydrogen of its cellulose, making it into a cloth of almost pure carbon, a charcoal cloth, a charcloth. Charcloth is the tinder of choice for use in the fire piston.

The plan: start a fire without matches to vindicate myself, show

Homo erectus

and

Homo neanderthalensis

what fire starting is all about, use a Dyak trick to create a flame. I drive an hour north of Anchorage and head up a trail that runs along Eagle River, toward its glacial source. But for the remains of thick drifts, the snow here is gone. The ice that covered the river two weeks ago has reverted to liquid and flowed away, to be replaced by more water from the glacier upstream, flowing in light whitewater around gravel bars and beside gravel beaches. Beyond the beaches, new buds of willow, poplar, and birch turn the landscape green. Higher up, Dall sheep graze, spread across almost vertical terrain. Sunlight warms my face and sparkles on the water, but a cold wind blows downriver, coming from the glacier in gusts.

I find reindeer moss along the trail, a species of lichen in the

Cladonia

genus, good for fire starting. I find dead spruce twigs covered with another lichen, this one sometimes called old man’s beard, in the Parmeliaceae family. I find twigs of dead and dried birch and branches of dead and dried poplar.

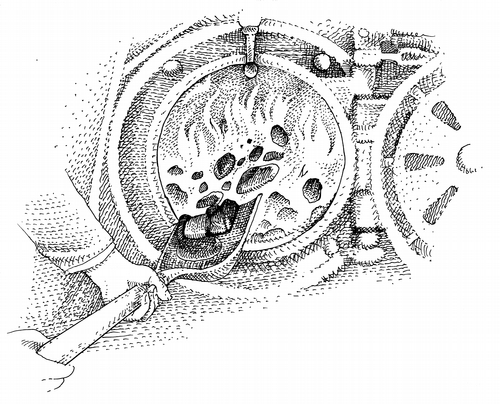

Three miles upriver, I step onto a gravel bar and drop behind a natural berm, a gravel and cobble wall three feet tall, carved by ice and floodwater. Beneath the berm, I build a small hearth of river rocks, flat rocks forming a base surrounded by round rocks forming a fire circle. On this river bar, there is no fuel other than what I carry. I pin my reindeer moss tinder to the hearth, using another rock to hold it in place, ready for a hot ember from my fire piston. I wad a piece of charcloth into the piston’s tinder chamber. I strike the piston with my palm, driving it forcefully into the cylinder. Nothing happens. I do it again with the same result. And again. After five failed strikes, I change out the charcloth, leaving threads of it protruding past the end of the tinder chamber, inviting flame. Five more strikes, but no ember, no glowing tinder.

I look closely at the piston, and the wind grabs the charcloth away, so I load another piece. My striking hand begins to ache. But strike fifteen yields a glow. I have ignition, charcloth glowing from the heat of compression.

I blow on the charcloth, then use the tip of my pocket knife to transport it onto the pile of reindeer moss. The ember smokes for a moment and then falls through the reindeer moss and into a crack between the rocks. My success fails.

I try again with new charcloth. If there is a trick to this, it is a trick that I do not understand. Or it is the trick of mindless repetition. I lose count after ten more failed compressions and two more bits of charcloth.

Then I have ignition again, a glowing ember. I drop the ember onto the reindeer moss. It makes the most smoke. The glow brightens, and the moss smoke thickens. But then the glow fades, and the smoke disappears. Another successful failure.

Giving up, I reach into my pack for my disposable lighter. This one is brand-new and full of butane. Boyle would be ashamed. Tyndall would be amused.

Homo erectus

and

Homo neanderthalensis

would question evolutionary theory. I change my mind. I put the lighter back in my pack.

I strike the piston again and again. A bruise forms on my palm, but I keep striking, driving the piston forcefully. Another glowing ember emerges. I kneel in front of my hearth with my nose inches from the pile of reindeer moss. Carefully, like a pharmacologist, I scoop the charcloth ember into the moss tinder. I gently blow. Smoke rises and thickens. And then, in a sudden flash, the moss ignites. I pile on old man’s beard and twigs of black spruce. The old man’s beard flares, and the twigs burn. I have a tiny fire. I feed in more twigs of birch and add branches of poplar.

I sit by the fire for a time, satisfied, knowing that the only difference between me and a Dyak tribesman is the need for mail order.

I generate something like twenty-two pounds of greenhouse gas emissions.

I eat peanut butter crackers, uncooked, while the smoke saturates my clothes. I reach into my pack and find my disposable lighter. Although it is brand-new, I dispose of it now, in my small campfire. I step back ten feet, then another ten feet. I watch the fire. I hear a sizzling noise and then a loud pop. A fireball explodes from the hearth. The remains of the lighter itself fly past my head.

A small disposable lighter of the kind that I just destroyed contains a tenth as much energy as a small stick of firewood, but it goes up in a flash, a single bang, its heat emitted as a ball of flame.

I return to my fire. The lighter’s warning label, blown off when the lighter ignited, is stuck to one of the rocks forming the fire ring. The label is charred but readable. “Never puncture or put in fire,” it says, and “Keep away from children.”

A

n hour north of Eagle River, weeds grow over steep mine cuts, sparse green fur on top of paradise lost. Erosion gullies are dry now, in July, but two months ago they would have run over with meltwater as the sun ate the snow. Moose tracks crisscross the slopes, along with piles of moose scat. Grizzly tracks cross the dirt trail on which I walk. A golden eagle soars overhead.

Off the trail, the mine cuts rise steeply. To walk upright is to fall. Progress upslope requires a crawling posture and the use of hands.

With my body stooped over and the sun at my back, my shadow falls across fossil plants. It is not a matter of a fossil plant here and a fossil plant there. Fossil plants litter the ground, imprints of unburned fuel. Here I find a piece of gray mudstone, flat, the size of a dinner plate, embossed with the outline of what looks like a poplar leaf and another of a sequoia. Here is more mudstone, this piece embossed with the stem of an equisetum. Here is a sliver of petrified wood and a branch of the same.

This is what is left of an Eocene forest, a fifty-million-year-old relic.

Eocene:

literally, the new dawn, a time after the loss of the dinosaurs, a time during which birds and mammals diversified and became obviously prevalent, a time when warm-bloodedness and its partner, fever, came into their own, the time of the Pakicetus, the Ambulocetus, the early whales.

Some of the fossils are crumbly aggregations of leaves. Others are more solid, with outlines of stems and branches. Some are bound to chunks of shining black coal. At the top of the mine cut, sweating from the climb, I find a petrified tree trunk, three feet in diameter, a place to sit.

Eocene plants captured the sun and stored its energy, batteries charged by a solar cell. A river ran through here, and intermittently, pools of water formed. Leaves fell from the plants and accumulated, along with twigs and stems and roots and whole trees, settling under shallow water. They became peat, a compressed mass of plant remains, a black garden mulch that forms when moisture blocks out oxygen. Mud and sand, carried in by flowing water, covered the peat. Over time, the weight of mud and sand squeezed out the water, and the peat became lignite, sometimes called brown coal or rosebud coal, a low-grade fuel stranded between peat and real coal but sometimes used to generate electricity.

The weight of more mud and sand, along with time, turns lignite into bituminous coal. When burned, bituminous coal produces twice the heat of lignite. Buried still longer, or deeper, bituminous coal became anthracite, almost pure carbon, a shiny black rock known variously as blue coal, blind coal, crow coal, stone coal, and hard coal. It burns hot, almost smokeless, with short blue flames. It produces little more heat than would come from bituminous coal, but it burns cleaner.

Marco Polo, traveling through northern China in the thirteenth century, saw coal in use. “Throughout the province” he wrote, “there is found a sort of black stone, which they dig out of the mountains, where it runs in veins. When lighted, it burns like charcoal, and retains fire much better than wood; insomuch that it may be preserved during the night, and in the morning be found still burning.”

I fly to the Netherlands, visiting family in the south, in Noord-Brabant, an area of neat rows of asparagus and mixed crops and the smell of pigs. The Netherlands, in Dutch

Nederland,

the low country or the low-lying country, is a nation of swamps and marshes, barely above sea level, in places below sea level, dry only by virtue of pumps and floodgates. It is a haven for peat.

My father-in-law, a man of eighty years, tells me of burning peat. During the war, he says, when the Germans occupied Holland, coal was not available. His family burned peat. They burned peat millions of years too soon for it to have become coal.

I visit the Groote Peel, a park that was once at the heart of the Dutch peat-mining industry. A display shows photographs of peat diggers and their tools. The men are weathered and lean, smoking, with the thousand-yard stare of manual labor. Their tools are wooden wheelbarrows and various kinds of shovels. There is the

stikker,

with a wide, flat blade; and the

kortizer,

a very short-handled spade; and the

klotspade,

almost identical to the sharpshooter spades used by soil scientists.

With the shovels, the men dug out bricks of peat, dripping clods of roots and decaying organic matter, eight inches long by five inches wide by three inches thick, the size of a large building brick. The men stacked the peat bricks in the sun to dry, leaving behind shallow pits with square sides, never more than a few feet deep.

The Dutch author Toon Kortooms lived near here, a short bicycle ride away. “Peat is a thick book,” he once wrote.

Born in 1916, Kortooms was one of fourteen children. His father managed a peat factory, where peat was converted to

strooisel,

or fuel pellets. His books put the boggy region of the southeastern Netherlands, the Dutch Peel, on the map. Among these books was the novel

Mijn Kinderen Eten Turf

, or

My Children Eat Peat

, based on the life of his father. The children, however, did not eat peat. Kortooms wrote figuratively. The father’s money had come from peat, and the food for fourteen children came from the father’s money.

In the book, as in life, the father burned peat in his stove. Late in the evening, he covered the burning peat with potato peels, forcing it to smolder through the night. In the morning the fire remained warm. He called the fire

de Goden

—the gods.

Rainy years were disastrous for peat mining. Dry years were better but could result in fires.

Peat pellets left the factory by steam-powered trains and wagons and long narrow boats that navigated the network of drainage canals. The pellets—

strooisel

—were used locally, but they also found their way to India, Palestine, South Africa, and the Canary Islands.

A competitor spied on the father’s business. The competitor followed customers and offered lower prices but sold peat that was not quite dry or that was laced with mud. “Het leek wel modder,” the competitor’s customers complained, “It looks like mud.” The customers returned to the father’s business, to a better-quality peat, happy to pay for a superior product, happy to become part of a rambling and eventually tedious Dutch parable of success.

The book ends with the father’s death. With him the era passes, the end of peat mining in the Peel. The Peel dies too, Kortooms tells us, the peat marshes killed in the peat-processing machines, converted to pellets. Where the peat was mined, only heather will grow, “small and desperate.”

In the Netherlands, large-scale peat mining is finished, but elsewhere it continues. Peat is burned to dry malted barley in Scotland, giving the famous peaty flavor to the best of whiskeys. It sometimes warms drinkers in Irish pubs, burned as bricks but more often as processed peat pellets, thoroughly compressed and dried so that it burns almost without visible smoke. A power plant in Finland burns peat to generate 190 megawatts of electricity, enough to power a city.

A small museum honors Kortooms, the father’s son, the miner of Dutch words, who died in 1999. The museum sits near the park, near the Groote Peel where his father mined, now a national park of swamps and heath and ponds that are the final product of peat mining. Here in the park, I follow a trail behind the visitor center, past a beekeeping display and its collection of hives, up to a viewing tower. From the top, I can see across the park to higher ground with fields of asparagus and mixed crops and cattle. Nettles grow along the edges of the fields. Despite the drainage canals, the park remains low lying and wet, a park as much for the sake of nature and history as for the reality of soils too saturated for farming.

Past the viewing tower, I come to a peat digging, a square-edged puddle, here as a demonstration. Twenty or thirty bricks of peat stand stacked next to the digging. The bricks are brown and laced with the stems, roots, and twigs of plants that died before I was born, but probably not too long before that, making them fibric peat, or young peat, less decomposed than hemic or sapric peat, a few million years short of becoming coal.

Next to the digging and the drying bricks, a sign, in Dutch, says, “Please do not take the peat.” I pilfer two bricks, stuffing them into my pack, and leave a generous donation on my way out.

By car, it is three hours and a hundred pounds of carbon emissions to go from southern Holland to Assen, in the north. I am here with my fourteen-year-old son to visit a bog person. The bog person, murdered two thousand years ago and embalmed in a peat bog, lies stored under glass in Assen’s tiny museum.

At the end of winding hallways and up short flights of stairs, beyond cases of stone ax heads and spear tips and hammers, beyond more cases of fired clay pots and bronze knives and a bronze tattooing needle—an inch long, green with oxidation, labeled “Bronzen tattoeernaald”—we find an isolated room. In the room, in her glass case, the bog person Yde Girl lies staring upward, eyeless, her body covered by a rough brown blanket, only her head and shoulders and feet and one hand exposed, the rest of her missing or too mangled or decomposed for display. Her skin, shriveled with desiccation, blackened by the tannins of peat, hugs the bones of her face. A lock of auburn hair lies next to her. A tiny tuft remains attached to her blackened scalp. Her mouth is open, as if in agony.

She lived around the time of Christ, around the time of Pliny the Elder. At the age of sixteen, she was killed, apparently by strangulation, possibly a victim of religious ritual. Nineteen hundred years later, in 1897, she was found by peat miners. Their tools left scars on her mummified carcass. The miners or their friends took her teeth and some of her hair and possibly a bone or two. They left intact the cord used to strangle her, which remains around her neck, under the glass, in the case.

I lean in for a closer look. I am inches from the pre-Roman Iron Age, inches from a woman who had lived at a time before matches, before steam engines and oil, before Faraday and Tyndall. Her people would have relied on wood for fuel, and possibly peat. They would have eaten bread from rough grains, the sort of bread that is available today only in boutique bakeries at premium prices.