Heat (7 page)

Authors: Bill Streever

In the morning, my urine flows weak and deep yellow. My lips are cracked, and my throat is scratchy in a way that drinking water does not soothe. My muscles ache. Despite the heat, I feel strangely chilled, as if I am fighting the flu. There is no question that my set point has been reset, nudged upward to a slight fever. I am thirsty yet have the feeling that a drink of water is just too much trouble.

My companion has trouble with her earrings. Her ears have swollen, closing the piercings.

We drive through the desert, stopping here and there for short walks. We drink water.

Late in the afternoon, we visit Badwater Basin. At 282 feet below sea level, it is Death Valley’s lowest point.

A hot, hard wind, a moisture-stripping wind, sweeps down from the mountains, carrying air that is more or less trapped in the valley. The hottest air rises from the surface of these salt flats, and in rising loses pressure, and in losing pressure cools. Before it can reach the tops of the mountains, before it can escape this valley, it grows cool enough to sink, and in sinking gains pressure, and in gaining pressure warms. It steals further warmth from the exposed earth of the mountainside.

The temperature in the shade at Badwater Basin is 124 degrees, but the only shade is that of my own shadow. The ground is almost pure salt and almost pure white. My metal pencil feels as hot as a stovepipe.

In Badwater Basin, I envy camels. I envy the way in which their body temperature fluctuates. I envy their ability to sustain a body temperature of 108 degrees without sweating. The camel’s loose coat reflects the sun. The surface of its coat may be thirty degrees warmer than its skin. Its head is plumbed in such a way that incoming blood is cooled, to protect the brain. When exhaling, it traps moisture in its nose. It produces urine as thick as syrup and twice as salty as seawater. It produces dung so dry that it can be burned fresh from the rump. It can store twenty gallons of water in its stomach and intestines. When dehydrated, it can gulp down fifteen gallons. Within a day, the badly dehydrated camel, given enough to drink, is rehydrated, healthy, and ready to go.

I am not a camel. Humans sweat with core temperatures as low as 100 degrees and just under half are dead from heatstroke before the core temperature reaches 108 degrees.

Twenty thousand years ago, Badwater Basin would have been six hundred feet underwater. The water flowed down from glaciers in the surrounding mountains, and when the glaciers disappeared, the flow stopped. The lake dried. The salts from the lake accumulated here. The salts form sharp ridges two inches tall that outline irregular polygons two and three feet across, stretching into the distance, stretching across this reflective basin, arid in the extreme.

The wind grows in strength until it impedes walking. It sweeps past us like the wind from a suddenly opened oven door. It is like the wind described by our guide at the Nevada Test Site, the wind from a bomb test that he felt passing overhead as he crouched in a trench. It engulfs me, blasting heat across my skin, between my fingers, behind my ears. It dries my eyes and my nostrils.

Over the mountains, thunderclouds form. I face into the wind and watch them approach. My shadow leans out across the salt. I smell ozone. I hear thunder. The clouds move quickly. A rainbow appears above Death Valley. I can see the rain, but it does not reach the ground. It disappears as it falls. But then I feel a drop, and another, and another. For twenty seconds, fine beads of water hit the ground, evaporating instantly on the hot salt. And then the rain is gone.

I

drive to Santa Barbara to visit a photographer. After his neighborhood burned, the photographer and his wife, wearing gloves and dust masks, sifted through the ashes. They invited friends. In what had once been their home, they found charred and broken dishes, globs of metal that had once been spoons and forks and clocks and lamps, burned books with pages turned to fragile ash. They found a copy of

Br’er Rabbit

burned around the edges, and they saw it as an object of novel beauty, an object of fire art. A magazine page, burned but for the image of a man’s face, emerged from the ashes. A mosaic made by the photographer’s mother surfaced, charred and in places melted, but worth salvaging. Half of a coil of green garden hose survived, its other half blackened and melted.

Four days after the fire, a friend found a wineglass in the ashes, picked it up, and was burned through her gloves.

The photographer, wearing his dust mask, in jeans and a white T-shirt, posed for a picture next to a metal file cabinet. The cabinet stood charred and warped, slumped under its own weight, a file cabinet that Salvador Dalí might have painted. The file cabinet once held the photographer’s best work: striking portraits of plantation workers in Sierra Leone, asbestos miners in Russia, a tribal woman smoking a pipe in Burma, Afghani men crouched in conversation. Before the fire, it had been a file cabinet full of images. After, it was a slumping metal hulk full of ashes.

The photographer talks quietly, forming thoughtful sentences that often end with an upward inflection. I ask how the loss of his house and his possessions and his photographs affected him.

“It was a sense of relief,” he tells me, “a feeling that we could make a new start.”

He and his wife and their friends gathered bits and pieces of fire-ruined goods. He talked to neighbors and borrowed artifacts from homes that had burned to ashes. In his studio, he put the artifacts in a light box. With soft light shining from below, the fire artifacts were framed in angelic white. With more light from above, the objects themselves were brilliantly lit. They are cataloged by the street addresses of now gone homes. Many are abstract shapes.

One picture shows what look like the metal remains of an antique revolver from 1325 West Mountain Drive, the wooden parts gone, the iron rusted. From 45 West Mountain Drive: a lightbulb that has lost its shape, its glass heat-softened on one side, allowing it to lean over with a dent in its heat-softened head. From the same house and the same fire: a ceiling fan with its blades and wires burned away, and a heart-shaped Christmas tree ornament now lopsided, a sheet metal angel of the sort meant to sit on top of a Christmas tree but now tragically drooping. From 350 East Mountain Drive: a pile of coins, copper faces green and twisted and unrecognizable. And from 245 East Mountain Drive: what looks like it could once have been a doll or a figurine, seated, with stubby feet and hands and thick limbs, hairless, its skin melted into globs and whatever face it had almost gone, its mouth now a gaping round hole that could be moaning or screaming, its eyes and nose burned flat.

The earth has been around for four and a half billion years. Fires such as the one that burned the photographer’s house did not exist for the first four billion of these years. The fire triangle—the triangle of heat, oxygen, and fuel—was incomplete on two sides. There were lightning strikes and lava flows to provide heat, but no oxygen and no fuel. Oxygen began to accumulate two billion years ago, pumped out of the oceans by algae, with levels becoming comparable to those of today five hundred million years ago. Around then, in the time of trilobites and ammonites, plants crept ashore. On mudflats and rock shelves close to the tide line, mats of algae developed. Moss evolved. A sort of fungus or lichen grew twenty feet tall with a trunk three feet thick. Club mosses and horsetails and ferns appeared on the scene.

Another name for these plants: fuel. The primitive land plants closed the fire triangle. The most ancient charcoal in the fossil record appears in the early Devonian, four hundred million years ago.

The powdery yellow spores of club mosses would eventually be used in fireworks and explosives. In the 1800s, along with candles, alcohol, phosphorus, and hydrogen, Faraday, during his candle lectures, burned club moss spores, calling the spores by the scientific name of the plant. “Here is a powder which is very combustible,” he wrote, “consisting, as you see, of separate little particles. It is called

lycopodium,

and each of these particles can produce a vapor, and produce its own flame; but, to see them burning, you would imagine it was all one flame.”

As plants crowded the land, they pulled carbon dioxide from the air and then died, locking that carbon dioxide away. The net effect was a cooling climate, a reverse greenhouse effect eventually offset as fuel accumulated and wildfires became common.

The nineteenth century French mathematician and physicist Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier, known for his work on vibrations and heat transfer, realized that the earth, based on its distance from the sun, should be a much colder planet. Its average temperature should be close to freezing, but in reality it hovers around sixty degrees. Why? He considered that heat might come from space, “from the common temperature of the planetary spaces.” He considered that the “earth preserves in its interior a part of that primitive heat which it had at the time of the first formation of the planets.” But in the end he focused on the atmosphere and oceans. For the most part, his work focused on the distribution of heat. “The presence of the atmosphere and the waters,” he wrote, “has the general effect of rendering the distribution of heat more uniform.” Heat from the tropics found its way north and south. But somehow—and he did not know how—the earth’s atmosphere trapped the heat of the sun. By virtue of the atmosphere, most of the earth was habitable.

Fourier, thanks to papers he published in 1824 and 1827, is widely credited with the discovery of what would become known as the greenhouse effect.

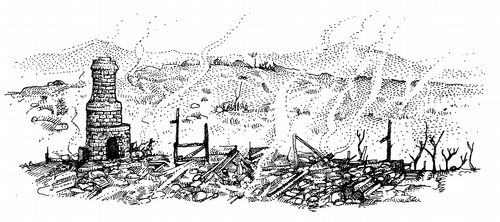

Before the photographer’s house burned, before it could burn, the atmosphere evolved. Four and a half billion years of change set the stage for the Tea Fire—the fire that took a photographer’s house and photographs, took his neighbor’s house too, burned or partly burned 219 homes spread across three square miles, converting prized possessions into misshapen lumps and fire art, but miraculously killing no one in its flames.

Heat, the first side of the fire triangle, was provided by college students who lit a bonfire up above Mountain Drive, near the abandoned ruins called the Tea House. The students said the fire was out before they left, but authorities suggested that the bonfire still held life, warm coals that the students missed. Fuel, the second side of the fire triangle, stood as dry chaparral, a shrubby mix of chamise and scrub oak and California lilac and black sage, with a few Coulter pines and the remarkably flammable Australian eucalyptus with their crowns well above the chaparral, perhaps even drier than normal with the effects of climate change. Oxygen, the third side of the triangle, rode in the air on a wind known locally as a sundowner, a wind that comes tumbling down the Santa Ynez Mountains, running toward the sea, warming as it loses altitude and gains pressure, like the winds that blow downward to fill Death Valley. Its warmth stripped the remaining moisture from plants while driving their flammable vapors into the air. The wind fanned the fire, turning warm coals hot, then hotter. Flames appeared around dinnertime and, pushed by the sundowner, moved downhill toward the houses.

As these things go, it was an average fire, a historical footnote, one fire in many. It was contained and controlled within days. During that time, more than five thousand homes were evacuated. Seven hundred and fifty-six firefighters were mobilized, with sixty-two fire engines. Something like six million dollars was spent in three days, and a thick-limbed doll was melted into an objet d’art, heated by the Tea Fire, along with a lightbulb, a pile of coins, an antique pistol, and a copy of

Br’er Rabbit

.

I drive a road through the hills and along the ridgeline above Santa Barbara with a scientist who studies, among other things, wildfire fuel. He looks at photographs taken from satellites and airplanes. From these photographs, he makes maps. Meaning in no way any disrespect to his science, I think of him as a mapper.

We can see Santa Cruz and the three islets of Anacapa Island and oil platforms off the coast, and the city of Santa Barbara surrounded by suburbs, and the suburbs surrounded on three sides by fuel in the form of dense chaparral. In places, orchards and highways form what may be thought of as firebreaks, separating the fuel of chaparral from the fuel of suburbia.

The Spaniards who ranched in California called the dense shrubby vegetation chaparral because it reminded them of scrub oak hillsides in Spain called

chaparro

. Cowboys chasing cattle into the chaparral invented chaps to protect their legs. In the heat of summer, they would have seen the chaparral burn just as it burns today.