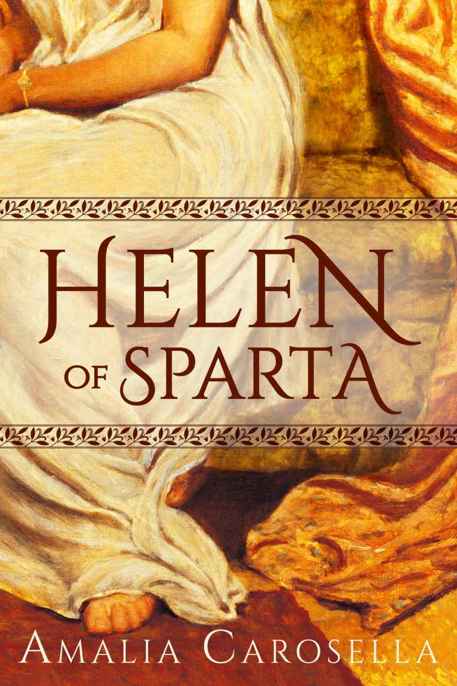

Helen of Sparta

Authors: Amalia Carosella

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Historical, #Literary, #Mythology & Folk Tales, #Historical Fiction, #Literary Fiction, #Mythology

O

THER

T

ITLES BY

A

MALIA

C

AROSELLA

Forg

ed by Fate

Fate

Forgotten

B

eyond Fate

Honor

Among Orcs

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, events, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Text copyright © 2015 Amalia Carosella

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Lake Union Publishing, Seattle

Amazon, the Amazon logo, and Lake Union Publishing are trademarks of

Amazon.com

, Inc., or its affiliates.

ISBN-13: 9781477821381

ISBN-10: 1477821384

Cover design by Anna Curtis

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014950871

For Mom, Dad, Zan, D., Biz, Laur, and, of course, Adam

CONTENTS

Zeus, the lord of all, who displays his might in everything else, considers it right to approach beauty in a spirit of humility. For in . . . the form of a swan, [he] won Leda for his bride, ever pursuing his quest of this gift of nature by stratagem and not by force.

—Isocrates,

Helen

FOREWORD

T

he world of Helen and Theseus is difficult to place precisely into the historical and archaeological record, but we do have some clues. Evidence suggests the Trojan War and the events leading up to it took place during a transitional time in history, at the tail end of the Bronze Age, and just a blink away from the collapse into a period referred to as the Greek Dark Ages. Homer is the first writer to emerge from these dark ages, some four hundred years later, and to ancient Greeks, his epics were more than just entertainment; they were the preservation of cultural history and memory. In ancient Greece, it was fairly well accepted that these events really happened, and the heroes involved rea

lly lived.

The archaeological record of Bronze Age Greece points to a highly organized and centralized government revolving around large palace complexes, which took insignificant inventories of goods from the surrounding communities, and then redistributed those same goods to their people and the larger region through wide-reaching trade. Craftsmanship was highly specialized, and of incredible quality, which itself suggests a foundation much more stable than subsistence living. It’s even possible that there was a healthy middle class at work! And these weren’t isolated communities, but, judging by the distribution of trade goods, complex networks in regular communication with their centers, as well as their neighbors, nea

r and far.

This is the world into which Helen and Theseus would most likely have been born, although at least one generation apart. Theseus, a son of both the god Poseidon and the mortal King Aegeus of Athens, was a contemporary of Heracles and Tyndareus, Helen’s adopted father. Helen, a daughter of Zeus (in the form of a swan) and Leda, was part of the generation that followed, including such heroes as Odysseus, Menelaus, Agamemnon, Diomedes, Achilles, and Paris and Hector of Troy. But as with all the most important and famous characters of myth and legend, Helen and Theseus’s generation gap doesn’t stop them from cross

ing paths.

By Helen’s time, Theseus was well into his reign as king of Athens, his heroic exploits far behind him. Theseus was known as a just and wise king once he settled to the task, and is even credited with the introduction of democracy to Athens. That isn’t to say he didn’t still engage in the occasional adventure. His best friend and fellow king, Pirithous of the Lapiths—another child of Zeus—wasn’t the best influence. It was in Pirithous’s company that Theseus made two very grave errors. The first was the abduction of Helen from Sparta, whom he then turned over to the custody of his mother for safekeeping before engaging in the second error, the failed abduction of Persephone, which resulted in the imprisonment of both Theseus and Pirithous in Hades. Pirithous, the instigator of both events, was never permitted to escape, but Theseus was rescued by Heracles. He returned home to Athens to find Helen stolen from him, and his people no longer interested in keeping him on as king. Ultimately, abducting Helen cost Theseus e

verything.

What Helen had to say about any of her experiences with Theseus, we don’t really know. Ovid addresses the abduction in passing from both Helen’s perspective and Paris’s in the

Heroides

, but beyond Helen’s insistence that Theseus treated her honorably—far more honorably than Paris intended to—and Paris’s implication that Theseus was a fool for not taking every advantage of her while he had Helen in his hands, very littl

e is said.

And in the myths that follow, Helen isn’t a very sympathetic character—maybe because her motivations are so unclear. No one can quite agree whether Helen went with Paris willingly, or even if she got as far as Troy in his company. Homer tells us she regrets intensely the Trojan War, even while it’s occurring, but she’s unwilling to act in the interests of either Troy or the Greeks (whom Homer refers to as Achaeans) to stop it. Though she helps Odysseus sneak in and out of Troy and speaks longingly of home, inexplicably she never gives herself up. She finds Paris to be cowardly and despicable, but she still makes love to him and stays by his side throughout the fighting. Even in the stories where Helen never arrives in Troy, it isn’t because she takes action on her own behalf but rather because Hera whisks her away to Egypt to wait for Menelaus, or because the pharaoh, offended by Paris’s violation of

xenia

—the most sacred law of hospitality—takes her from him before they can leave again. Helen appears to have very little power beyond the singular ability to incite lust, and even less agency. She is a plaything, a pawn of the gods, used to bring about the destruction of civilization, and an end to the Age

of Heroes.

But she doesn’t have to be. So much of Helen’s early life is a mystery, and even her abduction by Theseus is a footnote of

his

story, more than it is hers. In

Helen of Sparta

, I wanted to give Helen the opportunity for something better—a chance to take her life into her

own hands.

After more than twenty-five hundred years of texts in which she’s been pushed around by men and gods, I think she’s

earned it.

CHAPTER

ONE

I

gasped for breath, but my head was already beneath the water again, hard fingers digging into the back of my neck and holding me down. I tried to force my body to relax and willed myself not to struggle while my lungs burned for new air. My scalp stung. It must have been

bleeding.

“How could you, Helen?” Leda said, pulling my hea

d back up.

The ocher and walnut dye from my hair stained the water a muddy brown. I stared at it, gripping the edge of the raised tub to support myself while I caught my breath in great gasping heaves. My mother had always resented me, but I’d never expected to be half-drowned by her hands. As queen, she had always left this sort of mothering to

the maids.

“Do you not realize how this affects us all? Your beauty will secure you the finest marriage, and secure Sparta the finest king!” Leda attacked my scalp and hair with more sand

and soap.

The servants would be scouring brown dye off the stone tiles for days. If they scratched the finish, Leda would never f

orgive me.

“And just when Tyndareus is returning home with

Menelaus!”

She shoved my head back down into the water. I managed not to inhale any of it, but only just. I could still hear her cursing over the

sloshing.

Menelaus.

After long years in exile, he and his brother, with the support of my father, had spent the last year at war to reclaim Mycenae from his uncle Thyestes. Would the man who returned be the friend who had left me? I feared a year on campaign, a year at his brother’s side, would have hardened him, stealing the kindness he had always shown me. Or worse, what if he returned, and all he saw was my beauty? There was no denying this last year had changed me, and I could not bear the thought that he might look upon me with nothing but hunger and lust. So I had dyed my hair, and hoped it would be enough to keep him from wanting m

e at all.

But of course Leda could not understand my reluctance. To her, to Tyndareus, to all of Sparta, Menelaus would make the best match, the best king. Had he not been raised by Tyndareus as a son all these years? He was familiar already with Sparta’s strengths, Sparta’s people, Sparta’s needs. Even better, once his brother, Agamemnon, had retaken the throne at Mycenae, it would secure an alliance between our peoples. And he had always been my friend, showing kindness to me even when my brothers had grown tired of including me in their games, encouraging Tyndareus to soften my punishments, and taking the blame for some of my wilder

escapades.

But friends or not, I couldn’t marry him. Not after everything I had seen of what would follow. And the dreams were only getting worse, not better. Once, Menelaus might have looked upon me as a sister, but it would not be long before that changed. And I wouldn’t marry him. No matter what he desired. No matter what any of them wanted. I knew my duty to Sparta, to my people. Marrying Menelaus would only make the dreams, the nightmares, come true, and I could not allow that

to happen.

My lungs ached and my thoughts spun. Leda pulled my head back up at last, and I coughed and spluttered. She thrust a towel into my hands, but when I did not dry my face and hair briskly enough for her tastes, she took it back from me, rubbing hard. Water from the floor soaked through my shift. I already knew from testing the color that the dye would leave brown stains and the valuable linen would be spoiled. Leda would not forgive

tha

t

, either.

“I don’t want to be beautiful,” I said once I’d caught my breath. “I don’t want any

of this.”

She tugged painfully on my hair with the towel. “You are a princess of Sparta, Helen, and you will behave as one, with all the grace and beauty you’re capable of. Hera help us—you certainly won’t entice any man with you

r tongue.”

“You always told me that my beauty was my greatest curse, and I would never be free because of it,” I said, snatching the cloth back to dry my own hair more gently. “You said it would only cause trouble for everyone, that men would be driven mad just from looki

ng at me.”

Leda made a noise of exasperation, deep in her throat. “I did not mean you should ruin yoursel

f, Helen.”

I caught one of the wet strands, relieved to see the dye had not washed away entirely. My hair was an even muddier brown than the water—dull and unattractive where it had once been shining gold, bright a

s the sun.

“It will grow o

ut, Mama.”

“Not before the banquet tonight.” She stepped back, studying me through narrowed eyes. “Perhaps a scarf of some sort will hide the worst of it. If only you had done a proper job of it. Walnuts and ocher. What will Menelaus think of you now? He will hardly want you as a bride with spotted brown and bl

ack hair.”

“I thought there would be other men, greater men than Menelaus. Isn’t that what you said when

he left?”

“King Theseus did not let even his Amazon bride cause trouble like you do! If you insist on behaving like a drunken centaur, we will be lucky if any man at all will

have you.”

“Good.” I stood, twisting the cloth of my shift to wring the worst of the water from it before letting the embroidered hem fall back to my ankles. Even the braided ends of the belt at my waist had been stained. “I don’t care. I don’t want to marry any

of them.”

“Impossible child!” She grabbed me by the arm, her nails digging into my skin. “Would you leave your people without a king? Let them be conquered and made slaves? Put to their deaths? If only Sparta were inherited by its sons. Better the kingdom fall to Pollux than to such a spoiled, fool

ish girl.”

“Let Clytemnestra be queen of Sparta instead. She is Tyndareus’s true daughter. By all rights, it is her husband who sho

uld rule.”

“You are the daughter of Zeus, Helen. It must be you! The gods demand it, and I will not let this kingdom suffer because of your selfishness. When you are queen, the gods will smile on Sparta, and then perhaps Zeus will grant us his forgiveness

at last.”

The gods. Always the gods. Useless statues and temples—what power the gods might have had was spent on punishing us for their own divine sins. Leda feared Zeus especially. Everyone knew the story of her rape by the swan, though why Zeus would take such a form escaped me utterly. However violent the circumstances of my conception, I could not believe Leda would ever let a bird assault her in such a way, no matter how beautiful. But here I was, named a daughter of Zeus, and Clytemnestra, merely the daughter of a mortal king, though we had been born twins. Conceived the same day, according to Leda. First Zeus had come, and then she had sought the comfort of Tyndareus’

s embrace.

It wasn’t the first time Zeus had claimed her, for my twin brothers, Pollux and Castor, were said to be the result of a similar affair, but it was certainly the first time Zeus had shamed her so utterly by the act, inspiring her with unnatural lust. And then to see me, the daughter Zeus had forced upon her, named heir to Sparta—it was insult to h

er injury.

“You rely too much on the favor of fickle gods

, Mother.”

Leda struck me so hard, my head sna

pped back.

I stumbled, steadying myself on the tub before I fell. My lip had split. I sucked at the wound, and flashes of nightmares danced behind my eyes. Blood and a golden city, burning bright in the darkness. Menelaus, the man who had always treated me as a sister, regarding me with a loathing that made my stomach turn even more violently than the stench of burning flesh rising from the smoldering ashes. The bronze taste of my own blood only solidified the images i

n my mind.

I didn’t dare speak of it. One dream might be overlooked, but as often as I woke screaming in the night, I was sure to be taken by the priests if they knew the truth, if they knew I remembered the nightmares as clearly as my days. And it was not likely they would ever give me back. As a daughter of Zeus, I was too great a prize. Tyndareus might be king of Sparta, but not even he could protect me if the priests claimed me for the gods. For t

hemselves.

I would not be their slave, and I was not so great a fool as to believe an oracle’s life was anything else but that. Slavery and servitude, and poppy milk until I could not tell the world around me from my dreams. No. If I must serve—and as a Spartan I knew my duty, no matter what Leda believed—I would serve my people. Not the gods who punished us so cruelly, and not the priests who grew fat on our offering

s, either.

Leda dragged me from the small single tub, past the wide spring-fed pool, which served as the communal bath for the women’s

quarters

, and into

the hall.

“You will not insult the gods while you live under my roof, princess or not.” Her voice was as hard as her hand had been, and her nails dug deeper into my arm. “I have suffered enough for you already! That you live at all is only for Zeus

’s favor.”

She flung open the door to my room and threw me inside. I tripped into the bed, my wrist twisting uncomfortably beneath my weight. I cried out, but she did n

ot soften.

“You will stay in your room until your father arrives to decide your punishment. Do you understand m

e, Helen?”

I nodded, mute. In her anger, Leda had lost all her grace and beauty. Her face was cold, and I flinched beneath her glare. She looked upon me as if I were the broken shards of an urn, useless to her in every way. And then she swept out of the room, shutting and barring the door b

ehind her.

This was another reason why I had kept the secret of my dreams from everyone but my brother Pollux—Leda would be all too happy to see me sent away to Delphi with the blessings of the gods, and gone from her sight. She would never risk the anger of the gods by fighting the future they had ordained; Zeus had taught her too well to fear him. But me? Zeus had no use for me at all but for this death and destruction, and in that, I would never serve him willingly, no matter what my mother feared wou

ld result.

My mother barked at a servant to guard my room, her tone sharp. I would miss my lessons today, but my tutor, Alcyoneus, was not foolish enough to bother Leda when she was in a rage, especially when he was guilty of telling me how to mak

e the dye.

It would be a bad day for the palace slaves, and Leda would make sure they all

blamed me.

I lay on the bed, staring at the star-painted ceiling as the morning sun rose to its zenith. From my room I could hear Leda shouting at servants in the kitchens, the noise of preparation floating up from the courtyard below

my window.

Clytemnestra and I had been given an inner room to ensure our safety if the city ever came under siege, for Tyndareus had never forgotten how it had been taken from him once before. My sister complained frequently that she wished we had a room on the opposite side of the women’s quarters, so she might watch the men sparring in the practice field beneath the palace wall. From the second story, the view would be ideal, and we might even have glimpsed the edge of the city over the wall, with its red-tiled roofs and square, whitewas

hed homes.

I tried to stay awake, but my eyelids began to droop. As I drifted toward sleep, the shouts took on the quality of warriors and crying children instead of servants preparing a feast. I could hear Menelaus sometimes, calling my name, his voice hoarse with fury, and Agamemnon bellowing at the soldiers. Or worse, I heard him laughing while women

screamed.

In this dream, I am naked. Ajax the Lesser pulls me from the temple, dragging me through the streets of the city. Bodies and blood spill in the dust, and the Achaean soldiers are ransacking the houses of the dead. Women huddle against the brick walls, sobbing as they try to cover themselves with the tattered shreds of their robes. It is now beyond the point of fighting. All those who might have struggled are dead or subdued. When I don’t move quickly enough, my captor jerks me forward, shoving me before him. My legs are slick and sticky, my body sore, but I keep walking, through the courtyard and into the palace, and then into the megaron. The central hearth fire has been smothered with corpses of soldiers, stripped naked, and piles of bloody swords and armor sit waiting to be loaded into carts and hauled to the shore. The room stinks so much of human waste, I would be grateful to choke

on smoke.

Agamemnon sits on a golden throne, richly detailed with rearing stallions among emeralds and rubies. He leans forward when he sees us and smiles slowly, his eyes traveling over my body, full of lust and greed. A chill slips down

my spine.

“Helen, my dear sister-in-law. It is so good to see you delivered safe

at last.”