Hell (13 page)

When I’ve

finished the last one, I lie back on my bed and reluctantly pick up Billy

Little’s twelve-page essay. I turn the first page. I cannot believe what I’m

reading. He has such command of language, insight, and that rare gift of making

the mundane interesting that I finish every word, before switching off the

light a few minutes after ten. I have a feeling that you’re going to hear a lot

more about this man, and not just from me.

2.11 am

I am woken in

the middle of the night by rap music blasting out from a cell on the other side

of the block. I can’t imagine what it must be like if you’re trying to sleep in

the next cell, or even worse in the bunk below.

I’m told that

rap music is the biggest single cause of fights breaking out in prison. I’m not

surprised. I had to wait until it was turned off before I could get back to

sleep. I didn’t wake again until eight minutes past six. Amazingly, Terry can

sleep through anything.

I write for two

hours, and as soon as I’ve completed the first draft of what happened

yesterday, I strip down to my underpants, put a towel round my waist, and place

another one on the end of the bed with a bar of soap and a bottle of shampoo

next to it.

My cell door is

opened at eight

twentythree

. I’m out of the starting

gate like a thoroughbred, sprint along the corridor and into the shower room.

Three of the four showers are already occupied by faster men than I.

However, I

still manage to capture the fourth stall, and once I’ve taken a long

press-button shower, I feel clean for the first time in days.

When I return

to my cell, Terry is still fast asleep, and even a prison officer unlocking the

door doesn’t disturb him. The new officer introduces himself as Ray Marcus, and

explains that he works in the censor’s department and is the other half of June

Stelfox

, who took care of my correspondence on House

Block Three. His job is to check every item of mail a prisoner is sent, to make

sure that they’re not receiving anything that is against the regulations: razor

blades, drugs, money – or even food. To be fair, although the censors open

every letter, they don’t read them. Ray is carrying a registered package which

he slits open in front of me, and extracts a Bible.

The eleventh

in nine days.

Like the others, I donate it to the chapel. He then asks

if he can help in any way with my mail problem. Ray, as he prefers to be

called, is courteous and seems almost embarrassed by the fact that I’m not

allowed to open my own post. I tell him not to worry, because I haven’t opened

my own post for years.

I hand over

three large brown envelopes containing all the letters I’ve received the day

before, plus the first week (70 pages) of my handwritten script, together with

twelve first-class stamps. I ask if they can all be sent back to my PA, Alison,

so that she can carry on as if I was on holiday or abroad. He readily agrees,

but points out that as senior censor, he is entitled to read anything that I am

sending out.

‘That’s fine by

me,’ I tell him.

‘I’d rather

wait until it’s published,’ he says with a grin. ‘After all, I’ve read

everything else you’ve written.’

When he leaves

he doesn’t close my door, as if he knows what a difference this simple gesture makes

to a man who will be locked up for twenty-two hours every day. This privilege

lasts only for a few minutes before another officer strolling by slams it shut,

but I am grateful nevertheless.

Breakfast.

A bowl of cornflakes with UHT

milk from a carton that has been open, and not seen a fridge, for the past

twenty-four hours.

Wonderful.

Another officer

arrives to announce that the Chaplain would like to see me.

Glorious

escape.

He escorts me to the chapel – no search this time – where David

Powe

is waiting for me. He is wearing the same pale beige

jacket, grey flannel trousers and probably the same dog collar as he did when

he conducted the service on Sunday. He is literally down at heel. We chat about

how I’m settling in – doesn’t everyone? –

and

then go

on to discuss the fact that his sermon on Cain and Abel made it into

Private Eye

. He chuckles, obviously

enjoying the notoriety.

David then

talks about his wife, who’s the headmistress of a local primary school, and has

written two books for HarperCollins on religion. They have two children, one

aged thirteen and the other sixteen. When he talks about his parish – the other

prisoners – it doesn’t take me long to realize that he’s a deeply committed

Christian, despite his doubting and doubtful flock of murderers, rapists and

drug addicts. However, he is delighted to hear that my cell-mate Terry reads

the Bible every day. I confess to having never read Hebrews.

David asks me

about my own religious commitment and I tell him that when I was the

Conservative candidate for Mayor of London, I became aware of how many

religions were being

practised

in the capital, and if

there was a God, he had a lot of disparate groups representing him on Earth. He

points out that in

Belmarsh

there are over a hundred

Muslims, another hundred Roman Catholics, but that the majority of inmates are

still C of E.

‘What about the

Jews?’ I ask him.

‘Only one or

two that I know of,’ he replies.

‘Their family

upbringing and sense of community is so strong that they rarely end up in the

courts or prison.’

When the hour

is up – everything seems to have an allocated time – he blesses me, and tells

me that he hopes to see me back in church on Sunday.

As it’s the

biggest cell in the prison, he most certainly will.

Mr

Weedon

is waiting at the

chapel door – sorry, barred gate – to escort me back to my cell. He says that

Mr

Marsland

wants to see me

again. Does this mean that they know when I’ll be leaving

Belmarsh

and where I’ll be going? I ask

Mr

Weedon

but receive no response. When I arrive at

Mr

Marsland’s

office,

Mr

Loughnane

and

Mr

Gates are also

present. They all look grim. My heart sinks and I now understand why

Mr

Weedon

felt unable to answer

my question.

Mr

Marsland

says that Ford Open

Prison have turned down my application because they feel they can’t handle the

press interest, so the whole matter has been moved to a higher level. For a

moment I wonder if I will ever get out of this hellhole. He adds, hoping it

will act as a sweetener, that he plans to move me into a single cell because

Fossett

(Terry) was caught phoning the

Sun

.

‘I can see that

you’re disappointed about Ford,’ he adds, ‘but we’ll let you know where you’ll

be going, and when, just as soon as they tell us.’ I get up to leave.

‘I wonder if

you’d be willing to give another talk on creative writing?’ asks

Mr

Marsland

. ‘After your last

effort, several other prisoners have told us that they want to hear you speak.’

‘Why don’t I

just do an eight-week

course,

’

I reply, ‘as it

seems we’re going to be stuck with each other for the foreseeable future?’ I

immediately feel guilty about my sarcasm.

After all, it

isn’t their fault that the Governor of Ford hasn’t got the guts to try and

handle a tricky problem. Perhaps he or she should read the Human Rights Act,

and learn that this is not a fair reason to turn down my request.

A woman officer

unlocks the cell door, a cigarette hanging from her mouth,

*

and tells

Terry he has a visitor. Terry can’t believe it and tries to think who it could

be. His father rarely speaks to him, his mother is dead, his brother is dying

of Aids,

he’s

lost touch with his sister and his

cousin’s in jail for murder.

He climbs down

from the top bunk, smiles for the first time in days, and happily troops out

into the corridor, while I’m locked back in. I take advantage of Terry’s

absence and begin writing the second draft of yesterday’s diary.

Terry returns

to the cell an hour later, dejected. A mistake must have been made because

there turned out to be no visitor. They left him in the waiting room for over

an hour while the other prisoners enjoyed the company of their family or

friends.

I sometimes

forget how lucky I am.

Association.

As I leave my cell and walk along the top

landing, Derek Jones, a young double-strike prisoner, says he wants to show me

something, and invites me back to his cell. He is one of those inmates whose

tariff is open-ended, and although his case comes up for review by the Parole

Board in 2005, he isn’t confident that they will release him.

‘I hear you’re

writing a book,’ he says. ‘But are you interested in things they don’t know

about out there?’ he asks, staring through his barred window. I nod. ‘Then I’ll

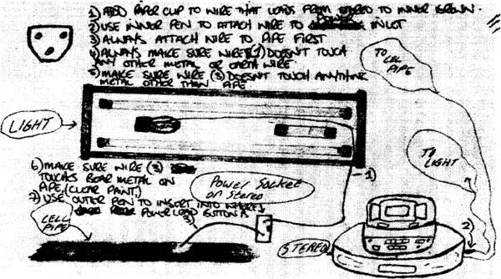

tell you something they don’t even know about in here.’ He points to a large

stereo in the corner of the room – probably the one that kept me awake last

night. It resembles a spaceship. ‘That’s my most valuable possession in the

world,’ he says. I don’t interrupt.

‘But I’ve got a

problem.’ I still say nothing. ‘It runs on batteries, ‘

cause

I haven’t got any ice.’

‘Ice?

Why would you need ice for a ghetto blaster?’

‘In Cell

Electricity,’ he says laughing.

‘Ah, I see.’

‘Have you any

idea how much batteries cost?’

‘No,’ I tell

him.

‘£6.40 a time,

and then they’re only good for twelve hours, so I wouldn’t be able to afford

any tobacco if I had to buy new batteries every week.’ I still haven’t worked

out where all this is leading. ‘But I never have to buy any batteries, do I?’

‘Don’t you?’ I

say.

‘No,’ he

replies, and then goes to a shelf behind his bed, and extracts a biro. He

flicks off the little cap on the bottom and pulls out the refill, which has a

coil of thin wire wrapped around it. He continues. ‘First, I make an earth by

scraping off a little paint from the water pipe behind my bed,

then

I take off the plastic cover from the strip light on

the ceiling and attach the other end of the wire to the little box inside the

light.’ Derek can tell that I’m just about following this cunning subterfuge,

when he adds, ‘Don’t worry about the details, Jeff, I’ve drawn you a

diagram

.

That way,’ he says, ‘I get an uninterrupted supply of electricity at Her

Majesty’s expense.’

My immediate

reaction is, why isn’t he on the outside doing a proper job? I thank him and

assure Derek the story will get a mention in my story.

‘What do I get

out of it?’ he asks. ‘Because when I leave this place, all I have to my name

other than that stereo is the ninety quid discharge money they give you.’

*

I assure Derek

that my publishers will pay him a fee for the use of the diagram if it appears

in the book. We shake on it.

Mr

Weedon

returns to tell me that

I am being moved to a single cell. Terry immediately becomes petulant and

starts shouting that he’d been promised a single cell even before I’d arrived.

‘And you would

have got one,

Fossett

,’

Mr

Weedon

replies, ‘if you hadn’t phoned the press and grassed

on your cell-mate for a few quid.’

Terry continues

to harangue the officer and I can only wonder how long he will last with such a

short fuse once he returns to the outside world.

I gather up my

possessions and move across from Cell 40 to 30 on the other side of the

corridor. My fourth move in nine days.

Taal

, a six-foot four-inch Ghanaian who was convicted of

murdering a man in

Peckham

despite claiming that he

was in Brighton with his girlfriend at the time, returns to his old bunk in

Cell 40. I feel bad about depriving

Taal

of his

private cell, and it becomes yet another reason I want to move to a D-cat

prison as soon as possible, so that he can have his single cell back.

I spend an hour

filling up my cellophane bag, carrying it across the corridor, emptying it,

then

rearranging my belongings in Cell 30. I have just

completed this task when my new cell door is opened, and I’m ordered to go down

to the hotplate for supper.