Read Helliconia: Helliconia Spring, Helliconia Summer, Helliconia Winter Online

Authors: Brian Aldiss

Helliconia: Helliconia Spring, Helliconia Summer, Helliconia Winter (2 page)

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTIONThe premise of

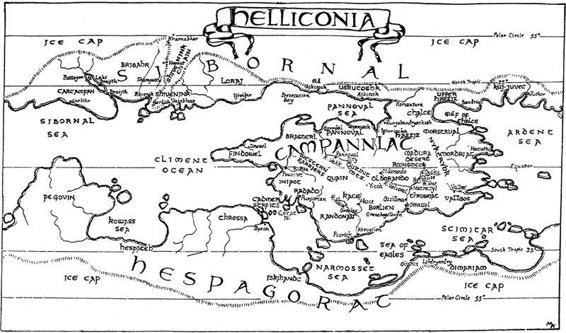

Helliconia

can be set out in a sentence, but it takes hundreds of pages to understand fully what it means. The planet Helliconia is locked into an orbit around two stars that gives it a ‘great year’ equivalent to 2,592 of ours. The three volumes making up the trilogy – originally published as

Helliconia Spring

(1982),

Helliconia Summer

(1983), and

Helliconia Winter

(1985) – chart this cycle. As the planet warms, the human-like inhabitants gain ascendancy over the savage phagors, but this pattern is reversed as the great year turns back to winter.

Helliconia

is not the last science fiction work by Brian Aldiss – he has had 25 years of productive writing since it was published – but it’s easy to see it as a capstone for his work. It certainly embodies ideas he was working out in earlier books like

Non-Stop

(1958) and

Hothouse

(1962). They were concerned with how humanity discovers, or fails to discover, its place in a universe shaped by forces out of its control. In those books, knowledge of the true situation isn’t especially consoling, but there’s still great value attached to applying rationality to the world.

Helliconia

marks something new in Aldiss’ work in the detail of its invention and the rigour with which the setting is presented. In a book like

Hothouse

, the flora and fauna of the garish future are described with a kind of joyous abandon. In

Helliconia

, there’s still the same fascination with how the world works, but a more rigorous sense of how the ecosystem fits together. Aldiss acknowledges many scientists who helped him put together the picture of Helliconia: not least is James Lovelock, whose Gaia Hypothesis proposes that the elements of the Earth’s ecosystem interact far more intricately than we might think. Helliconia’s ecosystem is certainly elaborate, and

the relationships within that system – between humans and phagors, say – are gradually revealed through the story.

In his history of SF,

Billion Year Spree

(1973), Aldiss talks at length about his admiration for writers of the scientific romance such as H. G. Wells and Olaf Stapledon. They too valued empirical investigation even as they warned about its limits and dangers. The scientific romance tends to use the viewpoint of a detached observer rather than a participant in the events described – think of the traveller in

The Time Machine

or the disembodied narrator of

Star Maker

. Yet Aldiss has always been interested too in individual humans and their struggles. In

Helliconia

, the detached viewpoint is provided by the Earth space station Avernus, orbiting Helliconia and relaying its events back to our solar system. But what occupies the bulk of these books is the story of people like Yuli or Luterin and their efforts to fight for or preserve what seems most precious to them.

A couple of things can be picked out from this vast tapestry. The first, as I suggested above, is the idea of struggle.

Helliconia

is the very opposite of an abstract book because it’s so rooted in personal stories. There’s always the sense that what’s most valuable about human society is potentially at risk and needs to be fought for. The second is self-knowledge. It’s always significant in Aldiss’ work when someone knows, or becomes aware of, their place in the universe. So the dialogue between science and religion, as for instance between the king and CaraBansity in Chapter II of

Helliconia Summer

, is especially important. The third is how images of cyclical change recur throughout the work, from the quotations by Lucretius that start the first and third books to the waves climbing and retreating from the shore at the start of the second.

Helliconia

is so rich with invention that I could easily spend ten times as long as this introduction discussing it. One final image, though, is how often the human story we’re shown

argues against

the environment it’s in. At the very end of the sequence, Luterin feels ‘exhilaration’ even though the vast winter is closing in; so even though the wind smothers his shouts, we know that spring will come again.

PREFACE

A publisher friend was trying to persuade me to produce a book I did not greatly wish to write. Trying to get out of it, I wrote him a letter suggesting something slightly different. What I had in mind was a planet much like Earth, but with a longer year. I wanted no truck with our puny 365 days.

‘Let’s say this planet is called Helliconia,’ I wrote, on the spur of the moment.

The word was out.

Helliconia!

And from that word grew this book.

Science of recent years has become full of amazing concepts. Rivalling SF! We are now conversant with furious processes very distant from our solar system in both time and space. Cosmologists, talking of some new development, will often say, ‘It sounds like science fiction.’ A perfectly just remark, reflecting as it does the relationship that exists between science fiction and science.

This relationship is not capable of precise definition, since science permeates our lives, and both scientists and writers are wayward people. It is a shifting relationship. What is clear is that science fiction functions in predictive or descriptive mode. It can attempt either to stay ahead of science, to foresee future developments or discontinuities; or it can dramatise newly achieved developments, making the bare (and, to some, arid) facts of science accessible to a wide readership.

An example of the former method (the ‘Wait and See’ method) is Gregory Benford’s novel,

Timescape

, in which he talks of the intricacies of time in a way which has only recently entered discussion by the scientific community.

An example of the latter method (the ‘Digestive Tract’ method) is H. G. Wells’

The Time Machine

, in which he demonstrates, as it were, the possibility of solar death – a startlingly new idea when Wells wrote.

In

Helliconia

, the Digestive Tract method is employed. In 1979, while this book was a mere building site, its foundations open to the alien sky, James Lovelock published a small book entitled

Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth

. The name Gaia was suggested by Lovelock’s friend (I might even claim him as a friend of mine) William Golding, the novelist. The classical Gaia was the goddess of the Earth in Greek mythology; Lovelock was outlining an impersonal updated version of that gubernatory personage. Lovelock pointed out that the continued survival of a living Earth is miraculous. Life survives despite an amazingly narrow range of chemical and physical parameters – parameters subject to fluctuation.

How is it that the Earth’s temperature has not long ago increased, as has happened on ‘our sister planet’ Venus; that the salinity of the oceans has not become more toxic than the Dead Sea; that atmospheric oxygen has not become tied down in oxides, or that hydrogen has not escaped from the upper atmosphere? Lovelock’s answer, known as the Gaia Hypothesis, is that everything on the earth, the biomass, constitutes a single self-regulatory entity – living, of course, but of course without conscious intention. Gaia has no particular centre, no prime minister or parliament, no

Führer

; not even a Greek goddess; it functions through its unfocused complexity, built up over millions of years. The implication is that the work of bacterial and other forces has built, and maintains, the living world we know, best to suit themselves – a process in which humanity has played small part.

I gave myself up to James Lovelock’s arguments in his first book and succeeding ones in the way that, in an earlier phase of existence, I had surrendered myself to Thomas Hardy’s novels.

Interestingly, Lovelock is an independent biologist of a rather old-fashioned kind, unsupported by universities or other institutions. And his hypothesis relies on the mode of close observation and enquiry which is such a marked feature of Charles Darwin’s

work. Darwin perceived where we merely see. Lovelock points out that what he calls ‘city wisdom’ has become almost entirely centred on problems of human relationships; whereas, in a natural tribal group, wisdom means giving due weight to relationships with the rest of the animate and inanimate world.

He says, ‘I speak from personal experience when I say that those of us who go forth in ships to travel to remote places … are few in number compared with those who chose to work in city-based institutions and universities.’

From travel, investigation, and perception, Lovelock built up his integrative hypothesis. I was wildly excited by it. Whether it was

true

or not, I felt that it was just and should be proved by research, and that here was a thesis which delivered new understanding. Lovelock wrote during the period of the Cold War, when we lived in the shadow of nuclear war, and the threat of nuclear destruction, followed by nuclear winter. Had nuclear winter come about, it would have been the ultimate profaning of nature, the rape and slaughter of Gaia.

These intellectual and emotional ideas were in my mind when I sat down to the seven-year task of writing

Helliconia

. I hoped in it to dramatise on a wide scale the workings out of Lovelock’s hypothesis.

The story between these covers is just a scientific romance. It talks about pretty ordinary fallible people living within fallible systems, just like us – together with the alien who also has a share in us. Although it may not look like it, I did not intend to place a great scientific emphasis on this introduction. SF, that spectral entity, is not science but fiction, bound to obey many of fiction’s ordinary rules, possibly with an extra imaginative dimension – there is no proof whatsoever that life exists elsewhere in the galaxy.

Deeply interested in the workings of the world of affairs, of economics and ideology and religion, I had written a novel (

Life in the West

) concerning such matters, of which I was merely a bystander. The novel met with enough success for me to hope to do something similar on a larger scale.