Henry IV (53 page)

Authors: Chris Given-Wilson

It was shortly after this that Ormond, perhaps taking advantage of the disturbance, launched a ‘great war’ against the Geraldines to assert his superiority in Munster, for which he was scarcely reprimanded, let alone punished. Indeed he may have had covert official sanction, because he was

high in Prince Thomas's favour, and in May 1403 had been deputed to open and adjourn the Irish parliament at Waterford.

25

Such partisanship made it difficult for the lieutenant and his deputies to claim to be governing on behalf of all the English of Ireland, but by this time the prince was wearying of his task. Lack of money had undoubtedly hampered his effectiveness. In August 1402 Archbishop Cranley wrote to the king informing him that his son ‘has not a penny in the world . . . [and] his soldiers are departed from him, and the people of his household are on the point of departing’. In total, during the two years that Thomas remained in Ireland, only about 50 per cent of what his father had promised him was actually paid, and by the summer of 1403 his accumulated arrears stood at £9,156.

26

On 1 September, with his sixteenth birthday approaching, his father gave him permission to return to England.

27

He sailed from Dublin in November, and would not return for five years.

Thomas's departure left his deputy, Stephen Le Scrope, as the effective governor of Ireland, and it was clearly a surprise when two months later Le Scrope followed the prince back to England without making arrangements to cover his absence. A great council thus met in March 1404 to choose an acting governor, and although it was said – doubtless correctly – that the earl of Ormond was elected by the assembly, his appointment must have met with official approval, for he continued to hold office until Le Scrope's return and was reappointed when the deputy crossed to England a second time.

28

The earl's first task was to suppress the continuing revolt in Ulster, for which he was granted a subsidy. During the next eighteen months he also took the opportunity to secure favours and promotions for a number of his friends,

29

a policy resented by Desmond, Kildare

and others, although to Prince Thomas it was a price worth paying for the political support he could offer. However, on 7 September 1405, aged around forty-five, Ormond suddenly died at Gowran (County Kilkenny). His death, said a Gaelic annalist, left the English of Ireland ‘very powerless’; it also threatened to unravel the prince's policy for governing his father's colony.

30

Henry's approach to governing Guyenne reveals both similarities and differences from his approach to Ireland. The traditional oaths of homage and allegiance extracted from towns and nobles at the outset of the reign reflected the feudal, and thus in practice more conditional, basis of his rule in the duchy, as did the efforts made to consolidate the support of vassals with a history of loyalty such as the lords of Duras, Caumont, Montferrand and Lesparre.

31

Nonpar de Caumont was confirmed as seneschal of the Agenais and received many favours, but it was the appointment of Gaillard de Durfort, lord of Duras, as seneschal of Guyenne which was especially noteworthy, for it was nearly a century since a native Gascon had held the post.

32

His appointment was also a money-saving measure, for as in Ireland the king seems initially to have hoped to make the rule of Guyenne largely self-financing. The English officials upon whom he relied were of respectable but not exalted rank, such as Sir John Trailly, who was confirmed as mayor of Bordeaux, and his constable, the trusted Henry Bowet, but more influential than either was the experienced Francesco Ugguccione, archbishop of Bordeaux since 1384, a cleric of international stature and a future cardinal. Nevertheless, as the supplanter of a king born in Bordeaux and the son of John of Gaunt, whose pretensions there had aroused such hostility in the early 1390s, Henry's acceptance as king-duke was never going to be a formality.

33

It was in the cities of Bordeaux and Bayonne that opposition to the new king was most vociferous, although only in the latter, where there was a brief takeover by an anti-Lancastrian faction, did it merit description as a rebellion.

34

This was doubtless what prompted Durfort and

Caumont to visit England in the spring of 1400, and to the appointment in May of Sir Hugh Despenser as the king's envoy to the duchy.

35

A firm but tactful visitation of Bayonne during the summer of 1400 sufficed to restore order there, and in the spring of 1401 both cities received pardons.

36

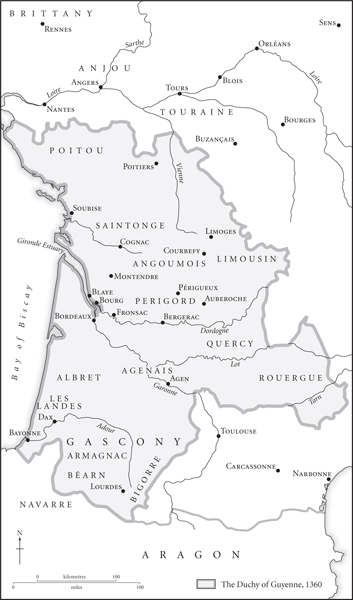

Map 7

The duchy of Guyenne

By this time, however, a mixture of bad luck (John Trailly and Nonpar de Caumont both died in 1400–1), rumblings of aggressive intent from Paris, and pleas from English supporters persuaded Henry that the retention of his duchy required the commitment of greater resources. Almost inevitably, it was Louis of Orléans who was the spearhead of French aggression. In January 1401 he persuaded Charles VI to make the dauphin duke of Guyenne, thereby signalling French intent to recover it.

37

Three months later the powerful Archambaud de Grailly, Captal de Buch, was tempted by the offer of the county of Foix to abandon his family's customary attachment to the English cause: on 28 March 1401 he swore allegiance to Charles VI, and a week later did liege homage in person to Orléans. Henry had done what he could to retain Archambaud's loyalty, either pretending or convincing himself that this was merely a temporary deviation from his ‘natural’ English allegiance, and his consistent refusal to condemn the count was probably a factor in the latter's unwillingness to commit himself irretrievably to Orléans's camp.

38

But meanwhile Duke Louis was busy staking his own claim in the duchy: already (since 1394) count of Angoulême, he was also granted the county of Périgord in May 1400 following the banishment and flight to England of the former count.

39

The possession of these two counties meant that Orléans's personal domain now marched with the Bordelais, and a raid into Périgord in June 1401 left any remaining English supporters there in no doubt as to what the future held for them.

40

Henry and his envoys expressed outrage at what they saw as Orléans's unprovoked attacks on English jurisdiction in Guyenne, but to Duke Louis, whose maximalist view of the French state saw the treaty of Brétigny as an aberration, the very presence of Englishmen claiming sovereignty within the borders of the French kingdom was a provocation.

Early in 1401 Archbishop Ugguccione wrote to Henry begging him to send the earl of Rutland, ‘the person who, after my lords your sons – who are still too young to labour thus far – is closest to your blood and to your heart’, and on 5 July the king's cousin was duly appointed lieutenant of Guyenne for three years at an inflated annual fee of £16,666.

41

He arrived in September accompanied by an impressive retinue: Robert Lord Scales, the veteran Matthew Gournay, seneschal of Les Landes, Edmund Thorpe as mayor of Bordeaux, and William Farrington, who replaced Henry Bowet as constable and would remain in the duchy for the rest of the reign. The new ruling council in Guyenne also included Guilhem-Amanieu, lord of Lesparre, and Bertrand de Montferrand, who along with Ugguccione and Durfort provided a solid wedge of local support.

42

Yet despite his semi-royal status and impressive list of powers, there is little to suggest that Rutland succeeded in imposing his authority in the duchy. Richard Ashton, keeper of the great stronghold of Fronsac on the Dordogne, proved reluctant to hand it over to him, and in May 1402 the English knights whom he led on to the field at Montendre were soundly beaten, even if the lieutenant himself did not take part in the combat.

43

By September 1402 Rutland was thinking of returning to England, probably in order to ensure his inheritance of the dukedom of York following his father's death, but by November he had changed his mind; within another month he had fallen out with William Farrington and imprisoned the constable in his own castle of Bordeaux.

44

In mitigation, Rutland could plead that he had great difficulty in securing cash from the English exchequer, and by May 1403 he had changed his mind once more and was on his way back to England, having (like Stanley in Ireland) completed barely half of his three-year term and received less than half of the amount promised to him. Meanwhile Orléans cemented the allegiance of the two greatest nobles in Guyenne, his cousin Charles, lord of Albret, whose appointment as constable of

France he secured in February 1403, and Bernard, count of Armagnac, who (like Waleran of St-Pol) became his vassal in return for an annuity of 6,000

livres tournois

. Brutal and feared, Bernard would support Duke Louis until his death, later giving his name to the Armagnac party.

45

This was the prelude to a succession of French assaults on English-held towns and castles in Guyenne, combined with a coordinated attempt to cut naval supply lines and disrupt maritime trade between England and the duchy. The latter was always one of the aims of the attacks on English shipping. The sack of Plymouth by Guillaume de Chastel on 10 August 1403 owed much to its role as the principal port of embarkation for Guyenne.

46

During the winter of 1403–4 naval blockades of Bordeaux and Bayonne were established.

47

It was the land war, however, upon which the main French effort was focused, and it was Orléans, nominated as captain-general in Guyenne in March 1404, who orchestrated it.

48

The main offensives were launched in mid-August and lasted for three months. To the east of Bordeaux, Constable Albret led a force of 1,500 men into the Limousin and Périgord, where a dozen English strongholds either surrendered or were stormed, including Courbefy, the most important Anglo-Gascon castle in the Limousin. Meanwhile Jean, count of Clermont, and Jean de Grailly, the sons of the duke of Bourbon and the count of Foix, respectively, led a campaign in the south of the duchy, first against Lourdes in the foothills of the Pyrenees and then into the southern Landes, some ninety miles south of Bordeaux, capturing another ten castles.

49

On 22 July 1404, presumably having heard that a French assault was imminent, Henry wrote some two dozen letters to lords, prelates and towns in Guyenne, thanking them for their support and reminding them of their allegiance to the crown. One of these, couched in the friendliest terms, was to the count of Foix, suggesting that his son's adherence to the French party was contrary to the count's wishes and asking him to restrain his activities. This had some effect, for Archambaud, ambivalent as ever about

his own allegiance, did attempt to limit the extent of his son's assaults.

50

Yet his performance of homage to Louis of Orléans in 1401 had undoubtedly damaged the English cause. Around this time, an English clerk in Bordeaux drew up a list of the nobility of Béarn and Les Landes, estimating the number of English and French supporters in each region. In Les Landes it was said that the nobility were English to a man, but in Béarn (held by the count of Foix) only sixteen noble houses were reckoned to be reliable while three were sympathetic to the French, seven were split between English and French allegiance, and two had declared their neutrality. Given that no one seemed very sure which side their lord supported, such liquid loyalties are not to be wondered at.

51

Meanwhile, loyal Gascons did what they could to repel the French onslaught: Gaillard de Durfort moved into the Agenais to defend Port-Sainte-Marie and a column of men from Bordeaux raided Albret's lands to the south of the city. However, the vacancy left by Rutland's departure in 1403 had not been filled, so that, encouraging letters apart, help from England did not stretch much beyond the modest retinues commanded by Sir William Farrington and Sir Matthew Gournay (the latter by now a septuagenarian), along with large quantities of wheat despatched from England between October 1403 and the summer of 1405 to relieve scarcity in the duchy, a measure of the efficacy of the French blockade.

52

Yet although the French successes of 1404 had failed to deliver a decisive blow to the English and their supporters, the capture of over twenty strongholds to the south and east of Bordeaux, many of them surrendered in return for financial inducements, left the city dangerously exposed to future onslaughts. With many of Albret's troops wintering in Cognac, less than sixty miles to the north, matters did not bode well for the new year.

To counter the threat, Henry turned in early 1405 to one of his most trusted knights, Sir Thomas Swynburne, appointing him mayor of Bordeaux; it would be he and Farrington, along with the loyal Gascon

lords and the citizen militias of Bordeaux, Bayonne and other towns, who for the next seven years would take responsibility for the defence of the duchy. Swynburne and Farrington, both by now middle-aged, belonged to that cadre of seasoned royal deputies who had spent much of their lives circling the perimeter of England's reach, learning to govern different outposts of the empire – a proto-colonial service.

53

Farrington had been seneschal of Saintonge in the 1370s, lieutenant of the captain of Calais in the 1390s, and had taken part in both of Richard II's Irish expeditions. He had also served as an ambassador to Rome and Portugal, and was an experienced naval commander and an expert on the law of arms. Swynburne had served since the 1380s as keeper of Roxburgh castle, captain of Guines and then Hammes in the march of Calais, and most recently, in 1404, as ambassador to the Burgundian court. He was well known to the king, for he had jousted at St-Inglevert in 1390 and visited the Holy Land at the same time as Henry in 1392–3. Following his arrival in Bordeaux in May 1405 with a retinue of fifty men-at-arms and a hundred archers, he immediately set about strengthening the defences of the city and its outlying forts – and none too soon, for the summer of 1405 witnessed the most direct assault yet on the heartland of England's duchy. In mid-August, 1,300 men led by Bernard of Armagnac made their way down the Garonne, capturing half a dozen strongholds before arriving in late September before the walls of Bordeaux. His advance was timed to coincide with the arrival in the Gironde estuary of three Castilian galleys led by Louis of Orléans's ally Don Pero Niño, count of Buelna, in the hope that a joint blockade of the city by land and sea would force its surrender.

54

Niño did manage to sail to within two miles of Bordeaux, doing a good deal of damage along the way, but he was driven off by the citizens on 26 September and a few days later Armagnac withdrew.

55