Here Be Dragons (41 page)

Authors: Stefan Ekman

A question that needs to be resolved when sampling a genre is what actually comprises the population. To address this question with some precision, I have borrowed terminology from the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. According to its

Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records

, a

work

is “a distinct intellectual or artistic creation,” an abstract entity that is realized through one or more

expressions

. A

manifestation

is “the physical embodiment of an

expression

” and can exist in a number of

items

.

3

For example, as J. R. R. Tolkien made constant revisions of the various impressions and editions of

The Lord of the Rings

, this work exists in a number of expressions. Each such expression is physically embodied in manifestations such as, for instance, the 2002 HarperCollins hardcover edition or the Houghton Mifflin 2004 Fiftieth Anniversary edition, each of which exists in a number of copies (items). Using these terms, we may ask whether a genre is a group of authors who write in the same vein or a collection of works that fulfill a certain set of criteria, or perhaps the totality of all expressions, manifestations, or even items that embody these works. If it is the authors, each author should appear only once in the sampling frame, and the probability for selecting Hope Mirrlees should be the same as for Terry Pratchett. That a writer who has published a single novel of genre interest would have the same impact on the genre as someone who has been writing steadily for decades seems dubious. Also, since we are investigating maps, it is reasonable to see the genre as a collection of fantasy works; the presence of maps

can

vary between expressions, but as a rule, if a work includes a map, a map is found in all of its expressions (although there are exceptions). I therefore decided to consider the population (the genre) to comprise all fantasy

works

, and to give each work in the sampling frame an equal chance of being selected for the sample.

Since listing every work in a genre is impossible, sampling the genre directly is likewise impossible. A popular method for a literary survey is to use an easily available

sample. (Deirdre F. Baker, for instance, describes her sampling thus: “I did a casual survey of the maps in some of the many fantasies I have on my own bookshelves.”

4

) Such a

convenience sample

, however, is almost certainly biased in one or more ways (in Baker's case, both by what books she has in her bookcase and by which of these she picked for her survey); there is no way of estimating the representativeness of the sample.

5

The survey in

chapter 2

draws its sample from a sampling frame, whose possible biases are detailed shortly. The largest database of fantasy books available to me was the inventory list of SF-Bokhandeln (Sweden's main science-fiction and fantasy retailer), which contained titles currently or previously in stock, or ordered, at the time when the list was copied to me.

6

I filtered the list for fantasy novels in English (according to the retailer's classification, it should be noted) and edited it: each title (work) was retained only once (separate editions, for instance hardback and paperback, resulted in multiple listings for some titles in the original list). Works considered not to be fantasy according to the criteria detailed in

chapter 1

were removed: Charlotte Guest's

Mabinogion

(1838â49), Walter Scott's

Ivanhoe

(1819), Thomas Malory's

Le Morte Darthur

(1485), and Penguin Classics of various “taproot texts” that predate the emergence of generic fantasy but that include the fantastic and are of heightened significance to the genre.

7

The following categories, while of genre interest, were also removed, as they were deemed to follow rules different from those for original works of fiction for including maps and would thus bias the sample: graphic novels (e.g., Neil Gaiman's Sandman sequence [1989â96]), obvious parodies (e.g., the Barry Trotter books [2001â2004] and

Bored of the Ring

[1969]), non-or semi-fiction spin-offs (e.g., Pratchett et al.,

The Science of Discworld

[1999]), and tie-in novels (novels based on worlds originally created in other media, e.g. role-playing and computer games).

Although the list offered a reasonable sampling frame of English-language fantasy currently or recently in print, I improved its correspondence to the population through supplementation in two ways. First, obvious gaps in a number of book series were filled in (e.g., if the first and third titles in a series were listed, the second title was added to the sampling frame). Second, as they could be considered central to the genre, any fantasy novels short-listed for the Hugo and World Fantasy Awards from 2000 to 2007 were added. If a short-listed work was part of a series, all the books in that series were added. For instance, for Gene Wolfe's

Soldier of Sidon

(2006; World Fantasy Award winner in 2007), the previous novels of the series,

Soldier of the Mist

(1986) and

Soldier of Arete

(1989), were also included. (In fact, most of the ninety-seven short-listed works and their pre-or sequels were already on the list, and only twenty-one additions were made.) After edits and additions, the final sampling frame contained 4,292 titles. From the sampling frame, 200 titles were then randomly selected (by computer-generated random numbers) and collected (listed in

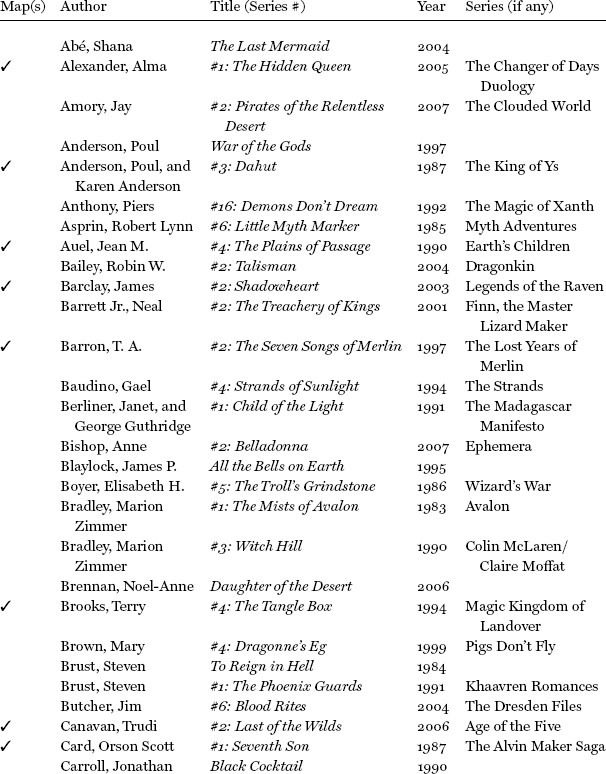

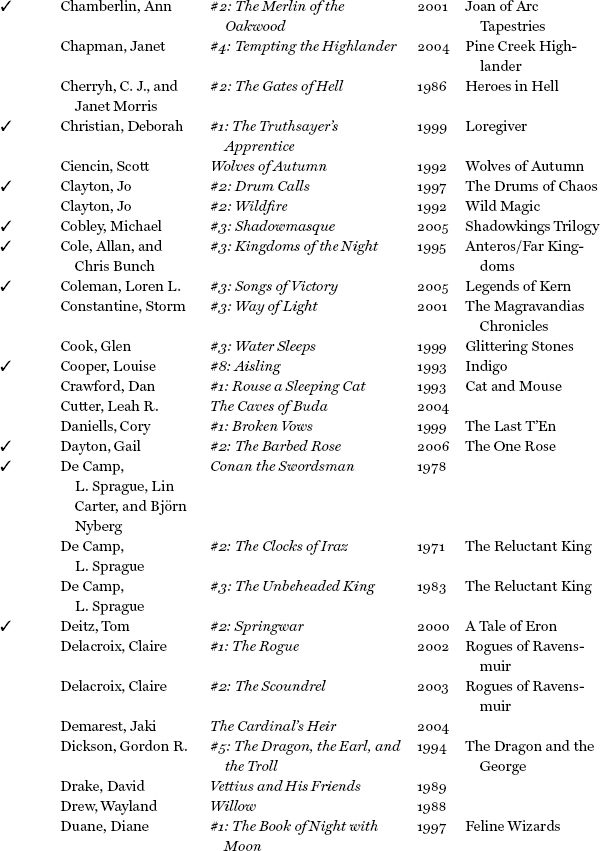

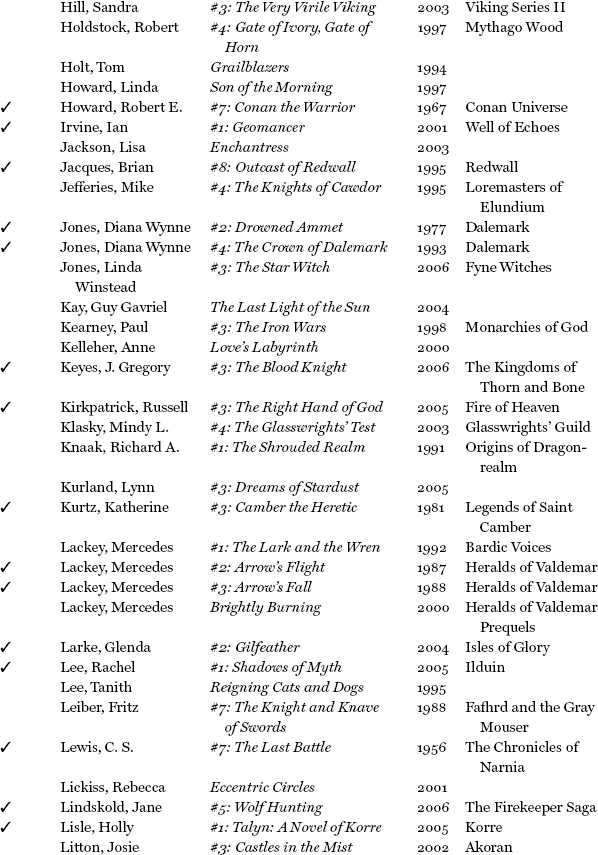

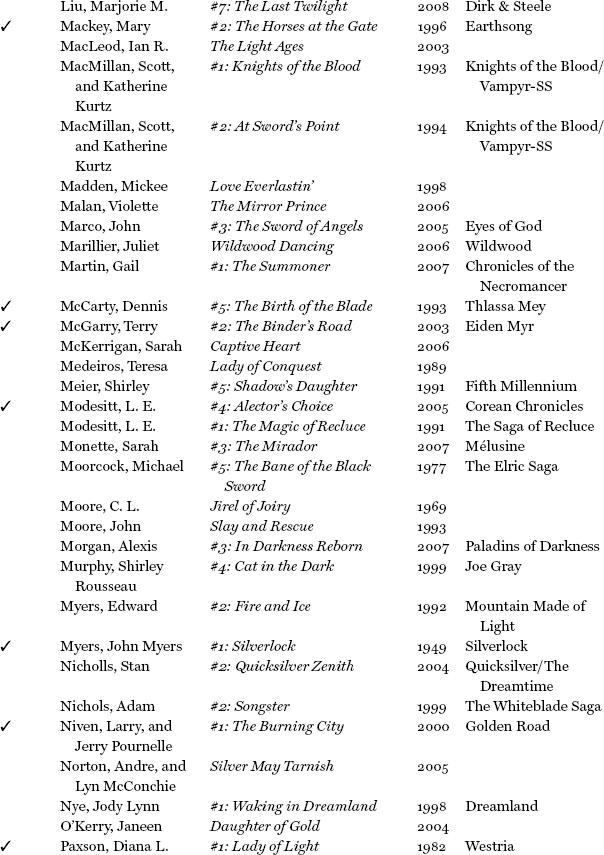

appendix B

).

Obtaining the exact editions in the sampling frame quickly proved too impracticalâand expensiveâso the sampling has been of the most readily available editions. As I take the genre to be a totality of

works

rather than

expressions

, this should not invalidate the sample. In some cases, I have been unable to get hold of copies of the books myself and have thus had to rely on others to scan or photograph the maps for

me. Partially for this reason, I lack data on the distribution between high and low fantasy in the sample.

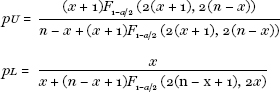

To determine the margin of error (at a confidence level of 95 percent), I used a method developed by G. H. Jowett. This method gives reliable calculations of potential errors and has the advantage of providing statistically correct margins of error regardless of sample size.

8

The margin of error gives the upper and lower limits between which it is 95 percent certain that the actual value for the total population lies.

Â

| p U | upper limit for margin of error |

| p L | lower limit for margin of error |

| n | sample size |

| x | number of units with the quality investigated |

| a | confidence coefficient |

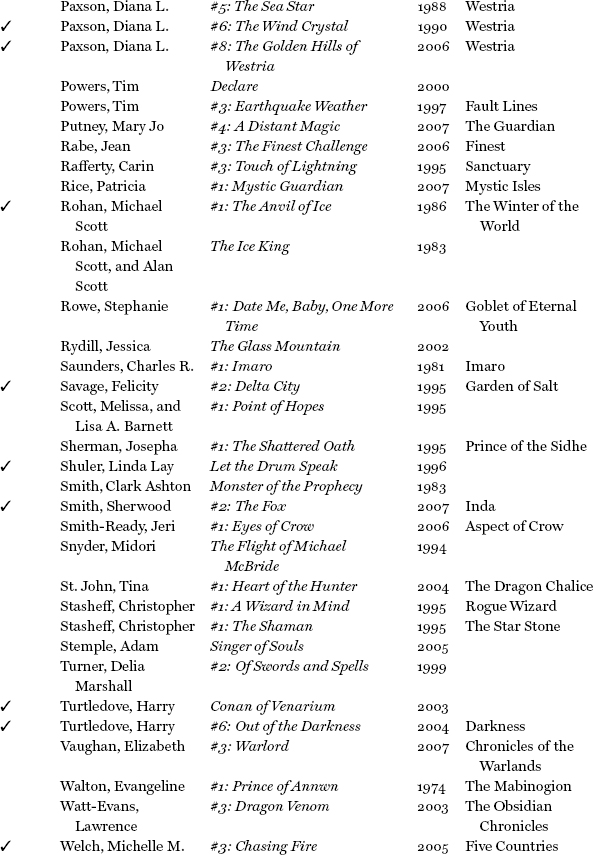

Appendix B: Map Sample