Here Be Dragons (6 page)

Authors: Stefan Ekman

The portrayal by at least two thirds of all fantasy maps of secondary worlds suggests a need in fantasy novels to provide a visual image of the imaginary setting, but also to provide the setting with some sort of structure. The map can help the reader understand complex spatial relationships that the text alone may fail to convey. Conversely, the absence of a map in a fantasy novel in which movements, positions, and spatial relationships in the imaginary world are central to the story may prove bewildering to the reader.

47

With maps of secondary worlds clearly dominating, the question arises to what extent these maps of alien worlds also reflect alien forms of mapmaking. In

The Hobbit

, Tolkien includes two maps, one of which

has

THROR

'

S

MAP

written in the lower left corner and includes some text in dwarvish runes. It is obviously meant to refer to a map in the story, and the brief preface points out that the map has “East at the top, as usual in dwarf-maps.”

48

The other

Hobbit

map, that of the Wilderlands, follows the convention of having north at the top. This convention is comparatively modern, however. According to historian P. D. A. Harvey, almost all world maps before the fifteenth century were either zonal (or climatic) maps or T-O (

orbis terrarium

) maps, circular maps with east at the top where the world is divided into three continents (Asia, Europe, Africa) by a T-shape.

49

In fact, of the extant medieval maps from the eighth through the fifteenth centuries, a clear majority are basic T-O maps.

50

2.2. MAIN SUBJECT OF MAPS

| Â | % of Maps in Sample (n) | % of All Fantasy Maps |

| Primary World | 14.1 (13) | 7.7â23.0 |

| Secondary World | 78.3 (72) | 68.4â86.2 |

| Imaginary City | 5.4 (5) | 1.8â12.2 |

| Building/s | 2.2 (2) | 0.3â7.6 |

N = 92

Despite the dominance of secondary worlds or historical settings in the sample, the maps largely follow the modern convention of placing north at the top. Ann Swinfen remarks on how (northern-hemisphere) fantasy writers maintain primary-world compass directions in their worlds.

51

A majority of all fantasy mapsâat least 58 percentâcome with a compass rose or similar design indicating which way north is. Other maps signal their orientation in other ways; for example, Southern Ithania is located below Northern Ithania in Trudy Canavan's

Last of the Wilds

(2005). For only nine maps in the sample can orientation not be determined from the map alone. Of the eighty-three maps for which orientation can be determined from the map, nine are not oriented with north at the top, but all are oriented so as to have a direction somewhere between northeast and northwest at the top. In the nine cases for which information about orientation is completely absent from the map, re-lated

maps or the texts in question have been used to work out how they are facing. North is at the top of all these maps except for one, which has north-northeast at the top.

2.3. MAP ORIENTATION

| Â | % of Maps in Sample (n) | % of All Fantasy Maps |

| N | 80.4(74) | 70.9â88.0 |

| NE to NW | 9.8(9) | 4.6â17.8 |

| No Orientation Given | 9.8(9) | 4.6â17.8 |

| Compass Rose | 68.5(63) | 58.0â77.8 |

N = 92

So although Thror's Map demonstrates the existence of fantasy maps that are oriented differently, such maps constitute less than 4 percent of all maps. Only very few fantasy writers or mapmakers avail themselves of the freedom to turn the map whichever way according to the conventions of imaginary societies in secondary worlds, or to create completely new directions. Instead, just as Swinfen suggests, the actual-world convention of orienting the map with north at the top dominates almost completely.

A typical feature of the T-O maps, a feature that, according to John Noble Wilford, goes back to the earliest extant world map (a Babylonian map from the sixth century B.C.),

52

is that the “whole [world] is surrounded by a circumfluent ocean.”

53

The surrounding water is where the world ends, where even the

possibility

of knowledge ends. It frames the known world, establishing that what is on the map is all there is. Similar circumfluent oceans can be found on fantasy maps, providing the worlds with what John Clute, in

The Encyclopedia of Fantasy

, calls

water margins

. According to Clute, these margins surround the central land or reality and fade away beyond the edges of any map. He adds that secondary worlds often have maps whose edges are water margins.

54

Such “ultimately unmappable regions”

55

that completely enclose the known world of a fantasy map within regions of the unknown are not, in fact, particularly common; only a small proportion of the fantasy maps are completely surrounded by water margins (9 to 24 percent;

see

Table 2.4

). On at least three maps out of four, land stretches to the edge of the map, suggesting that the world not only continues but is accessible. The term

water margin

is also slightly misleading; a water margin need not consist of water, but can be a region of any “endless” or “impassable” terrain type. Of the fourteen cases in the sample, two maps have water margins that are not water. In Terry Brooks's

The Tangle Box

(1994), the land of Landover is surrounded by a mountain range beyond which are “Mists and the Fairy World.” Brooks's fairy world, it is explained in the first Landover novel,

Magic Kingdom for Sale/Sold!

(1986), is a numinous place that borders on all worlds. It can be traversed but only with the help of magic; it cannot be mapped, it is unknowable.

56

In Martin Gardner's

Visitors from Oz

(1998), one of many late additions to L. Frank Baum's classic Oz books, the land of Oz is surrounded by an “impassable desert” (also described as “shifting sands,” “great sandy waste,” and “deadly desert”).

57

While obviously meant to emphasize the futility of any attempt to leave Oz by nonmagical means, other Oz books (for instance, the third book in the sequence,

Ozma of Oz

[1907]) allow for such journeys and open up a world beyond the land of Oz, which illustrates how water margins can be breached, the unknowable made knowableâand known.

The notion that a water margin must enclose the world completely is not unproblematic. On many maps from the sample, there is some land at the edge of the map, providing the possibility of larger landmasses unaccounted for by the mapped area. An example from the sample is Michelle M. Welch's

Chasing Fire

(2005), where a continent surrounded by water takes up most of the map but where a small part of another landmass (Ikinda) can be found along a section of its southern edge. It is obviously the continent that is the map's focus: it features mountains, rivers, and a lake, as well as political borders and various locations (mostly towns, presumably, but names such as Mt. Alaz, Seven Oaks, and Naniantemple suggest that other types of places may also be included). What can be seen of Ikinda, on the other hand, is completely empty. This might mean that it is featureless, unexplored, or simply irrelevant to the story. On the map, Ikinda is portrayed as unknown but knowable, not quite part of the water margin but almost. Welch's Ikinda is hence truly marginalizedânot only pushed to (and beyond) the edge of the map but also emptyâwhereas the map's central continent has a variety of features. Yet setting out to explore the parts of Ikinda that lie beyond the map edges is certainly possible, and such exploration might reveal a

small island or a vast continent. We cannot tell which from the map, yet we know that there is something there.

Even when there is a circumfluent ocean, however, the world can be opened up. Expeditions into the water margin have been undertaken in numerous fantasy works. In, for instance, Stephen R. Donaldson's Second Chronicle of Thomas Covenant series (1980â83), the Mallorean series (1987â91) by David and Leigh Eddings, and Raymond E. Feist's

The King's Buccaneer

(1992), sea voyages off the map turn up new continents. On the other hand, as the Landover and Oz maps have already demonstrated, terrains other than water can create an unmappable, unknowable region at a map's edge. The map in Gail Dayton's

The Barbed Rose

(2006) places the central land of Adara between sea to the east and west, whereas to the north and south there are mountains that give the impression of being impassable. The mountainous northern isthmus is called “The Devil's Neck,” a name that emphasizes just how impassable it really is. While this is not a complete margin in a strict sense, the map still makes clear that Adara is where the story takes place, and the reader who ponders what can be found beyond the mountains is left with a vague suspicion that there will only be more mountains. (Mountains as map elements will be discussed further in the text that follows.)

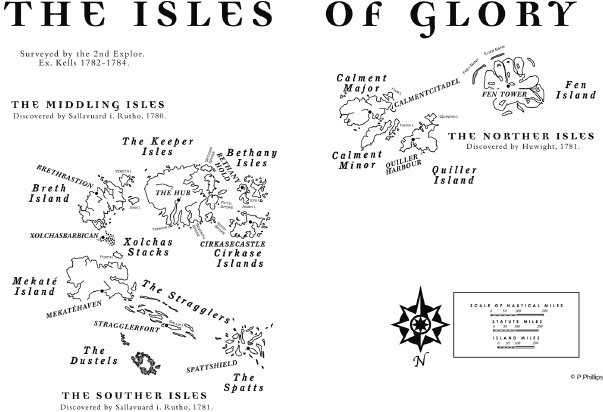

Even if the landmass on the map is fully surrounded by water, this does not necessarily constitute a water margin in Clute's sense. The map of the Isles of Glory (

map 2.1

) in Glenda Larke's

Gilfeather

(2004) may set its islands in a surrounding ocean, but comments on the map make plain that in the diegesis, there is no unknown world to discover beyond the edges of the map. Instead, the islands themselves have been discoveredâand, it is implied, fairly recently at that. Not only does the map tell us that the isles were “[s]urveyed by the 2nd Explor. / Ex. Kells 1782â1784,” but it also notes by whom and when the various parts of the archipelago were discovered. Known and unknown are turned around here, the well-known residing off the map. Wherever the political, financial, and cultural centers are to be found in this secondary world, they belong in the regions beyond the map's marginâthe Isles of Glory, in the middle of the map, are part of the world's periphery.

The absence of complete water margins, with at least some land reaching all the way to the map's edge, indicates that a map does not portray an entire world. Even when the map gives the impression of portraying the whole world, such as the map of Earthsea in Le Guin's

A Wizard of Earthsea

, an extremely short land border still suggests that there is

more to the world than this. It also implies that the region on the map is located somewhere in the larger world.

MAP

2.1. The Isles of Glory from Glenda Larke's

Gilfeather

(2004).

Copyright Perdita Phillips,

www.perditaphillips.com

.

Of the ninety-two maps in the sample, only one third are clearly set in the northern or southern hemisphere; for the rest, this distinction could not be determined from the maps. Obviously, a secondary world does not have to be set in a hemisphere; Terry Pratchett has demonstrated with his Discworld novels that a world shaped like a disc works as a setting. The change in shape also led to his abandoning the traditional compass points. Instead, the Disc has the main directions “hubward” and “rimward,” and the lesser directions “turnwise” and “widdershins.”

58

Of the thirty-one maps for which the hemisphere can be determined, twenty-five are set in the northern hemisphere, five in the southern, and one included both hemispheres.

In other words, the northern hemisphere is clearly more common, even when the margin of error is taken into account. One possible explanation is, of course, the preponderance of writers from the northern hemisphere. Despite a growing number of Australian and New Zealand

fantasy writers, the vast majority of fantasy writers in English come from the United States and Great Britain. Yet the five maps of a southern hemisphere actually come from three novels by three different writers (Ian Irvine, Sherwood Smith, and Harry Turtledove), with only Irvine hailing from the Antipodes.

59

Another possible interpretation would be that the cultural and political bias toward the northern hemisphere that we find in the actual world rubs off on the creation of secondary worlds and the maps that portray them.

2.4. SURROUND ELEMENTS

| Â | % of Maps in Sample (n) | % of All Fantasy Maps |

| Water Margins | 15.2(14) | 8.6â24.2 |

| Map Projection | 5.4(5) | 1.8â12.2 |

| Legend | 23.9(22) | 15.6â33.9 |

| Scale | 16.3(15) | 9.4â25.5 |