Here Comes the Night (24 page)

Next, Berns took the Isleys back in the studio after “Twisting with Linda,” the tepid follow-up to “Twist and Shout,” came and went. For the A-side of the group’s fourth single of the year, Berns harnessed the gospel fervor of the Isleys on their own rip-snorting “Nobody but Me,” but Florence Greenberg pressed the case for the single’s B-side, an unremarkable piece of typical Aldon pop, “I’m Laughing to Keep From Crying,” produced by Luther Dixon. (Overlooked in the Isleys’ original version, “Nobody but Me” would become a 1967 Top Ten hit and garage band classic by the Human Beinz.).

Whenever Greenberg did exercise her taste, the results were usually dreadful. Even Burt Bacharach, who had been delivering hit songs to the label, felt the chill of Greenberg’s controlling hand. She relegated Bacharach and David’s “It’s Love That Really Counts (In the Long Run)” to the B-side of the next Shirelles single, a quietly elegant piece, one of their finest, something that could have lifted the Shirelles out of the realms of the purely teenage. She submarined for purely personal reasons the exquisite Bacharach-David production of their “I Just Don’t Know What to Do With Myself” by Tommy Hunt, the former lead vocalist of the Flamingos, because the singer was dating both Beverly Lee of the Shirelles and the girlfriend of a Mafia don on the side and Greenberg didn’t approve. She had never thought much of Hunt’s voice; he was strictly Luther Dixon’s signing, but now Luther was gone.

Tired of the daily strain of running interference between Florence and the rest of the record company, being responsible for writing, rehearsing, producing virtually the label’s entire roster, all tangled up in his tormented personal relationship with his boss, Dixon accepted an offer to run his own label for Capitol Records. Under the same mandate that landed Berns and Roker their Lookapoo deal, not to mention the big money for Bobby Darin, Capitol Records, looking to expand their reach on the

Billboard

charts, set up Ludix Records. Dixon, according to

Billboard

, would continue to produce the Shirelles for Scepter. But with Dixon gone and the Isleys at the end of their string at Scepter, Berns would be a long time darkening those doors again.

“Pops” Maligmat owned a Filipino restaurant in Manhattan and wanted inexpensive entertainment, so he trained his four sons to play music. He kept their five sisters in Manila and put the boys out on the road at an age when most kids still needed babysitters. When former Roosevelt Music songwriter Neil Diamond saw the little cuties on

The Ed Sullivan Show

, he thought they’d be perfect for this Christmas song he wrote with a Latin beat. He took the idea to another former Roosevelt writer, Stanley Kahan, who had opened an office of his own

at 1650 Broadway. He told Diamond to send in the group to audition, never dreaming for a minute that they would. When “Pops” showed up with his four boys, ages nine to fourteen, and Kahan heard them play and sing, he signed the group in an instant.

With some money from United Artists, he took the Maligmat brothers, now called the Rocky Fellers, into the studio and cut Diamond’s Christmas song. When United Artists passed on the master, he took the tapes down the hall to Scepter Records. Kahan presumed Diamond’s frequent absences from the project had to do with the young songwriter’s college studies. But it turned out that Diamond suddenly had bigger fish to fry. He had signed a record deal with Columbia Records and was trying to wriggle free of any commitment he might have made to Kahan, who had given Diamond a piece of the Rocky Fellers. As a result, Diamond didn’t meet Bert Berns when Kahan brought Berns onboard the next Rocky Fellers record.

Berns had previously used songs by Kahan and his partner, Eddie Snyder, writing as Bob Elgin and Kay Rogers, on some of his Lookapoo Productions records at Capitol. Kahan was a tall, older guy with a big personality and winning ways. He wrote lyrics, and Snyder supplied the music. Berns and Kahan dreamed up a song, “Killer Joe,” that took its name from the dancer Joe Piro, known as Killer Joe, famous-at-the-moment around Manhattan discotheques. But Berns also built into the song a male jealousy angle that perhaps inserted a little more rage and angst than was appropriate for nine-year-old lead vocalist Albert Maligmat, cute as a Pres-to-Log. Even in dumb teenage dance songs, Berns liked to see his singers tortured.

Because the original production deal was still in place, Berns could only help produce the session uncredited, but that didn’t matter. He liked Kahan. Like Berns, he had come into the music business relatively late in life. He had managed a hotel in Miami and dabbled in songwriting, but there had been problems with finances and the IRS, and he moved back to New York to pursue songwriting full-time. He had only

recently opened his own office after being fired from Roosevelt Music three floors below. He was a wheeler-dealer, an entertaining, sociable fellow, life-of-the-party sort of guy. But there was something else about Stanley Kahan. It was something that people whispered about him, yet it hovered over him. Everybody knew it about him and it changed the way they saw him. It had to do with shadowy associations. There was a phrase for it. He was connected.

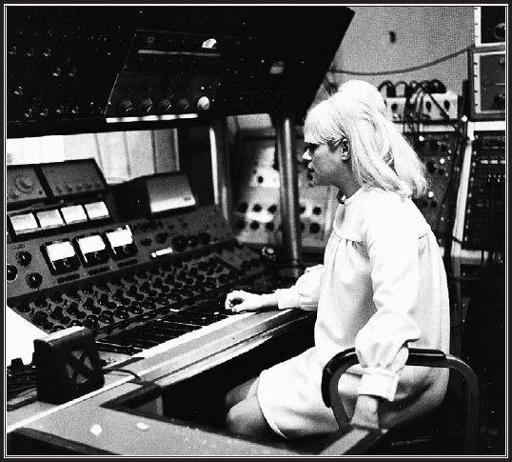

Ellie Greenwich at Mira Sound

N

EW YORK CITY

in the early sixties was the center of the modern universe, the largest city in the country, second largest in the world. Europe was still shaking off the dust of World War II and the dominance of American industry, commerce, and culture went unquestioned, much of it run by men with offices high in Manhattan skyscrapers. This was the big time, a sprawling, brawling mess of a city where money talks and the most goes.

These men running the rhythm and blues racket in New York were kings of what they liked to do. Provincial backwaters such as Chicago, Memphis, New Orleans, or Los Angeles could produce records, but nothing on the level of the New York scene. Behind the music publishers and record labels lay a skilled cadre of arrangers, studio musicians, and engineers, the best anywhere. Their world was invisible to the union musicians in the Broadway pit orchestras or the society dance bands, but to them, they were playing the only game in town. They loved these records and they brought their scientific best to bear on every session.

Studio musicians were a new, well-paid underclass of professional musicians. Many came out of the jazz world, gravitating toward lucrative work in recording studios as big bands disappeared and bandstand jobs evaporated. The work required flawless technical ability, a collaborative ethos, and rewarded the flexible, adaptable musician more than

the rigid stylist with the forceful, individual vision. Tenor saxophonist King Curtis was such a versatile musician.

Born Curtis Ousley in Forth Worth, Texas, he won the amateur contest at the Apollo while visiting relatives in New York and returned to Texas to go to college on a music scholarship. By the time he landed on the Atco label in 1958, he had played with Lionel Hampton, formed a trio with pianist Horace Silver, and recorded under his own name for a number of independent labels. By the end of the fifties, he was the first-call saxophonist for any r&b dates in New York, a musician who could find a place for himself in many different kinds of music, still retaining a readily identified sound and never descending into cheap, gaudy showmanship or screeching, honking histrionics.

He could play ropes and snakes with the beboppers, and even did a couple of jazz dates for Prestige as a leader in 1960 with some Miles Davis sidemen, but he more comfortably followed a mainstream style patterned after Lester Young, Arnett Cobb, and Gene Ammons. He could be tough on a bandstand. Other players would step up, thinking they were going to burn him, and Curtis would call something like “Giant Steps” in F sharp. He would routinely play notes two or three harmonics above the horn range, and fly through the traditional horn range itself, leaving the other players looking at their fingers.

Curtis became an integral part of Leiber and Stoller’s records with the Coasters, offering sly, insinuating commentary between verses written expressly for him by the songwriters. Leiber would sometimes stand beside him in the studio, whispering phrases in his ear as he played. He spent thousands on his wardrobe and always carried plenty of cash for his high-stakes gambling. A large, commanding presence in the studio, he grew to become a big man on the scene, often contracting the recording dates, lofting the occasional instrumental hit under his own name such as “Soul Twist” or the “Beach Party” single he did the previous year with Berns (his subsequent experiment in vocals that Berns also produced, “Beautiful Brown Eyes,” did not fare so well).

The brilliant but troubled pianist Paul Griffin was playing with the King Curtis band at Small’s Paradise in Harlem when he first met Bert Berns. The producer approached the young pianist, who grew up in Harlem and was in his second year of college, and asked him if he wanted to do some record dates. Griffin didn’t know what he meant. Berns told him to take out his datebook. Griffin still didn’t understand. Berns explained it to him and booked Griffin for a Solomon Burke session later that week. One day Griffin didn’t have a phone; the next day he had to get one and it wouldn’t stop ringing.

Gene Pitney watched as Phil Spector and Griffin lay on a studio floor, Griffin sketching out charts as Spector hummed in his ear. Burt Bacharach wouldn’t do a session without Griffin. He was unhappily married to an aspiring songwriter with a deal at Scepter named Valerie Simpson and he drank, but Griffin’s fluid, graceful, articulate playing was the backbone of every session he did.

Drummer Gary Chester replaced Panama Francis, a grumpy old man out of the Lucky Millinder band who handled most of the fifties r&b dates, as drummer of choice almost as soon as he played his first Leiber and Stoller session, backing LaVern Baker on “Saved” in 1960. Chester, an Italian raised in Harlem, ran away from home as a kid and never went to school. He won the Gene Krupa drum contest when he was fourteen years old and traveled with the jazz great for a while. He worked all over the Midwest and had settled into a routine of club dates and jingle sessions when he fell into the r&b work.

Chester was an unusual blond-haired, blue-eyed face behind the kit in the rhythm and blues world. He had his signature tricks, like resting a tambourine on his hi-hat or putting a sand-filled ashtray on his snare, but Chester was both a human metronome and a remarkably musical drummer who could smoothly navigate his way into the heart of a song. Whether he was reading or playing without charts, his drumming told a story. He memorized tempo changes. He could make the track heavy or make it skip along. He became an integral part of almost

every record by Leiber and Stoller, Bacharach, Berns, and others, burrowing himself into whatever music he was playing. Bacharach, in particular, liked to tie Chester’s drumming to Griffin’s piano playing and even encouraged the association by making those two set up next to one another in the studio.

Vocalist Cissy Houston came from so far deep in the gospel world, she didn’t feel comfortable even simply talking with white people when she first started doing sessions in New York. She sang with a family gospel group, the Drinkard Singers, under the direction of her minister father in Newark. The group was nationally known, played regularly on gospel bills at the Apollo, appeared at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival, and cut an album for RCA Victor in 1959, but she supported herself with a factory job making television picture tubes, ironically, for RCA Victor.

She was suspicious of pop music—her father never allowed it to be played in their home—when her husband first suggested singing on recording sessions. Instead he took the Gospelaires, a group started by Cissy’s teenage nieces Dionne and Dee Dee with some other kids from the New Hope young people’s choir. He shepherded the girls on the bus to the Port Authority and off to Times Square recording studios for sessions that would often run past midnight.

Even as her husband and nieces were making good money and booking work with producers like Leiber and Stoller, who used the girls on Drifters sessions, and Henry Glover, who made jazz and blues records for Morris Levy at Roulette, Cissy remained reluctant to take her music out of the church into the world. The night, however, when her niece Dionne was called to a Shirelles session, leaving the other girls without a top voice, she went along and sang rather than disappoint Glover and Levy with their underworld connections.

Burt Bacharach heard the girls at rehearsals for a Drifters session he arranged and noted the young funny-looking one in pigtails and tennis shoes with the high, piping voice. Soon he and Hal David were using

the twenty-one-year-old college student and substitute Shirelle to sing their demos. Dionne sang their demo for “Make It Easy on Yourself,” which turned into a breakthrough for the songwriters when it was recorded by Jerry Butler in 1962.

Butler had been the lead vocalist of the r&b group the Impressions who had the 1958 hit “For Your Precious Love.” With his colleague from the Chicago-based group, guitarist and songwriter Curtis Mayfield, he also cut the 1960 Top Ten hit, “He Will Break Your Heart.” His silken baritone proved perfect for the aching Bacharach and David melodrama.