Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (8 page)

Read Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia Online

Authors: Michael Korda

In Jidda they found HMS Euryalus, the flagship, with the commander in chief of the Egyptian Squadron, Vice-Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss, GCB, CMG, MVO, on board, on his way to Port Sudan to meet with General Sir Reginald Wingate, governor-general of the Sudan and sirdar of the Egyptian army, at Khartoum. This was fortunate for Lawrence: Wemyss—a widely respected naval figure and a friend of King George V—combined impeccable connections with a fervent belief in the possibilities of the Arab Revolt. Indeed, a visit on board Wemyss’s flagship had been one factor clinching the Arabs’ decision to revolt: they were awed by the size of its guns, and indeed astonished that a vessel so big and heavy could float at all.

Wemyss was no stranger to odd behavior—he kept in his day cabin on board Euryalus a gray parrot trained to cry out, in a pronounced Oxford accent, “Damn the kaiser!"—and he liked Lawrence, whatever headgear Lawrence wore. Wemyss, who would come to Lawrence’s help again, always appearing at the right moment unexpectedly like a wizard in a pantomime, took him across the Red Sea to Port Sudan, and from there to Wingate’s headquarters in Khartoum, where Wingate—the original and firmest supporter of the Arab Revolt—read his reports and listened to his opinion that the situation in the Hejaz was not dire, as many peoplein Cairo supposed, but “full of promise.” What the Arabs needed, Lawrence said, was not British troops, whose appearance at Rabegh would cause the tribesmen to give up the fight and return to their herds, but merely a few Arabic-speaking British technical advisers, explosives, and a modest number of modern weapons.

As it happened, this was exactly the message that the chief of the imperial general staff (CIGS) in London most wanted to receive, for the terrible battles on the western front in 1916 made manpower a crucial question. Verdun had cost the French nearly 500,000 casualties, and the first Battle of the Somme, launched by the British to support the French at Verdun, would cost them more than 600,000 casualties, 60,000 on the first day alone; and General Murray, the commander in chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in Cairo, was under constant pressure from the CIGS in London to squeeze every possible division, brigade, and person out of his army for immediate dispatch to France.

Lawrence was perhaps the only person in the world who would have described his three or four days at Wingate’s palace in Khartoum—on the steps of which Lawrence’s predecessor in the imagination of the British public as a desert adventurer, General Gordon, had been murdered—as “cool and comfortable.” Everybody else who had visited Khartoum at any time of year described it as hellishly hot, though certainly Wingate’s palace was plush and lavish after the desert, and surrounded by beautiful gardens. When Lawrence was not conferring with Wingate and Wemyss, he spent his time reading Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, a pleasure interrupted by the kind of event that seldom failed to occur at the right moment in Lawrence’s career. His host, Sir Reginald Wingate, was abruptly informed that Sir Henry McMahon had been recalled from Cairo to Britain, and Wingate was to take McMahon’s place as British high commissioner in Egypt. Thus supreme control of Egypt would pass from the hands of a civilian into the firmer hands of a soldier who supported the revolt passionately, who would be in direct command of the British end of it, and who knew Lawrence well. At the same time the change would bring to an end a curious division: political responsibility for the Arab Revolt hadbeen in Cairo and military responsibility in Khartoum, and this had been a source of delay and confusion to all concerned.

Both senior officers read and were impressed by Lawrence’s reports from the Hejaz. They were still more impressed by Lawrence himself; and it must be noted that, as was so often the case with Lawrence, though still a temporary second-lieutenant he was conferring as an equal with an admiral and with his excellency the governor-general of the Sudan and sirdar of the Egyptian army. This easy access to the most senior officers and officials was due not to Lawrence’s social position, which was less than negligible, but to his acute mind; to his strong opinions, which were based on facts he had personally observed; and to his view of policy and strategy, which was far broader and more imaginative than that of most junior officers—or, indeed, most senior ones.

In short, part of the reason for Lawrence’s success was that he knew what he was talking about, and could make his points succinctly even among men far senior to him in age, experience, and rank. Even the busiest of officials made time to listen to what Lawrence had to say: generals, admirals, high commissioners, and princes now, and in the not very distant future, also artists, scholars, prime ministers, presidents, kings, and giants of literature. Lawrence himself, though reasonably respectful of rank unless provoked, seemed almost unconscious of it, treated others as if they were all equals and was himself treated as an equal by many of the highest figures in the world. He may have been the only person in twentieth-century Britain who was just as much at ease with King George V as with a hut full of RAF recruits. Certainly, he eventually won Wingate over completely, and Wingate was not an easy man for a temporary second-lieutenant without a proper cap or uniform to win over.

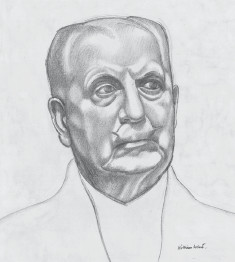

Unlike McMahon, whom he was to replace, Wingate was fiery, hot-tempered, and impulsive. One only needs to look at Wingate’s portrait in Seven Pillars of Wisdom to read his character: a square, bulky face straight out of Kipling, the expression angry and challenging, the eyes piercing, the sharp tips of the ferocious waxed mustache pointing straight out like horns—all this suggests the human equivalent of a Cape buffalo bull about to put its head down and charge. In the end, Wingate was too muchso for his own good; but this was exactly the spirit that was called for at the top if the Arab Revolt was to survive and prosper. Lawrence tended to describe the senior officers who crossed his path with distant and sometimes stinging irony, but he showed Wingate a rare degree of respect, despite serious differences of opinion between them on the subject of a British presence and—even less welcome to Lawrence—a French presence in Rabegh. Wingate no doubt terrified other junior officers, but it can have done Lawrence no harm that he, like Wingate, was a man of the desert. Wingate had fought in the Sudan and Ethiopia, had conquered the final remnant of the Mahdi’s Dervish army, and was at the same time a man of refined tastes and sensibility, who spoke and read Arabic fluently.

Lawrence therefore traveled back to Cairo by train with far greater confidence in his future than he had felt leaving it for Jidda with Storrs a month ago, though his optimism was to prove short-lived. In Cairo confusion reigned, stirred up in part by the impending departure of McMahon, and in part by concern for what was happening at Rabegh, owing to rumors that the Turks were about to attack. If the Turks were able to take Rabegh, they could outflank Feisal’s army and recapture Mecca, in which case the Arab Revolt would be over.

Wingate.

Happily, Lawrence, having just returned from the Hejaz and met Feisal, was in a position to calm these concerns. He was not alone in attributing them to Colonel Édouard Brémond, the head of the French military mission, who was as anxious to place a French military presence—in the form of North African Muslim soldiers and specialists—in Rabegh as most of the British were to keep them away. In the first place, the equivalent of a French brigade in Rabegh would mean that the British had to send one as well, and this the CIGS was unwilling to do. In the second place, the British were anxious to keep the French out of what was regarded as a British “sphere of interest.” Lawrence knew Brémond, a big and energetic man, a fluent Arabist with a wealth of experience in commanding Muslim troops in desert warfare; they behaved toward each other with exquisite courtesy but a complete lack of trust. Brémond reported to Paris on Lawrence’s anti-French sentiments, and Lawrence made no secret of his hope “to biff the French out of” the territory they coveted. The French colonial system, which operated so efficiently in Algeria and French Morocco, was exactly what Lawrence wanted to spare the Arabs: French settlers; a Europeanized native army with French officers; and the rule of French law, culture, and the French language imposed on those of the native elite who wanted something more for themselves and their families than looking after their herds, flocks, and fields in the desert. Lawrence had no great enthusiasm for the British colonial system, especially in India, but the French were undoubtedly more determined to impose French ideas and interests on the natives in their Arab colonies than the British were in theirs, and the result was that Lawrence often seemed more anxious to defeat France’s ambitions in the Near East than to defeat the Turks.

Lawrence’s future was already being discussed at the highest level before he was even back in Cairo. The CIGS himself suggested to Wingate by cable on November 11 that Lawrence be dispatched to Rabegh “to train Arab bands,” while in Cairo Clayton had finally succeeded in getting Lawrence transferred full-time to the Arab Bureau, to handle propaganda aimed at the Arabs. Having secured Lawrence, Clayton wasunwilling to give him up, and there followed a brief, polite tug-of-war between Wingate and Clayton over him, complicated by the fact that if he was sent to Rabegh he would be under the command of Colonel Wilson in Jidda (who had referred to Lawrence as “a bumptious ass”).

By this time the fear that Rabegh might fall had made its way up to the war cabinet in London, along with considerable pressure from the French government to place French “technical” units there to prevent this. Clayton ordered Lawrence to write a strong memorandum expressing his opinion that Allied troops sent to Rabegh would cause the Arab Revolt to collapse, which Clayton then cabled, unexpurgated, to the cabinet and to the CIGS. Thus, Lawrence’s views, which sensibly dismissed the possibility that Rabegh might be taken by the Turks so long as Feisal and his army were given the support he had requested, were accepted with relief in London, and quickly transformed into policy. Lawrence articulately presented his argument against sending the French units, as well as his belief that Yenbo, not Rabegh, was the important place, since it was nearer to Feisal’s army, and urged that every effort should be made to cut the railway line linking Damascus and Medina, rather than attempting to take Medina.

Neither the Foreign Office nor the CIGS seems to have been taken aback by the fact that diplomatic policy and military strategy were being formulated by a second-lieutenant in Cairo, perhaps because Lawrence’s opinions were so forcefully presented (and corresponded, in large part, with what everybody in London wanted to hear), and perhaps because Lawrence was the only person who had ridden out into the desert to see for himself what Feisal was doing. In any case, the result was—to Colonel Wilson’s great annoyance—that Lawrence was ordered back to the Hejaz to serve as a liaison officer with Feisal. On paper, he would be reporting directly to Wilson, but he would also be serving as Clayton’s eyes and ears in Feisal’s camp.

In Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence makes a grand show of his unwillingness to go, alleging that it “was much against my grain,” but this must be taken with a pinch of salt. In fact it seems more likely thatwhat Lawrence objected to was going to Rabegh, since this would place him too close to Wilson for comfort, whereas in Yenbo he would enjoy considerable independence, even more so once he journeyed inland and joined Feisal.

In any case, whether Lawrence went willingly or not, it was the first step on the road that would eventually turn him into perhaps the most celebrated, exotic, and publicized hero of World War I.

*

This was the equivalent of the viceroy in India, a post to which Kitchener aspired, but never attained.

*

What the czar actually said, during a conversation reported by the British ambassador in Saint Petersburg in 1853–in the course of which the czar raised the possibility that russia and Great Britain might split up the ottoman empire between them–was: “We have a sick man on our hands, a man gravely ill; it will be a great misfortune if one of these days he slips through our hands, especially before the necessary arrangements are made.”

*

A

kufiyya

(spellings differ in English transliterations of Arabic) is the Arab head cloth; and an aba is a long cloak.

*

Except when quoting from other sources, as i do here from Storrs, i have elected to use whenever possible Lawrence’s own spelling for Arab names and places, which is relatively phonetic, but not necessarily systematic. “Abdullah,” “Abdulla,” and “Abdallah” are all possible spellings, and of course refer to the same person. Since the maps in the book come from various sources, the transliteration of place-names in them is not necessarily consistent, but it is easy enough to follow.

*

Lawrence’s spelling of Arabic names and places is erratic, and so is Storrs’s, but I have preferred to quote from letters and documents as they were written, rather than imposing on them a false conformity.