Hetty Feather (3 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

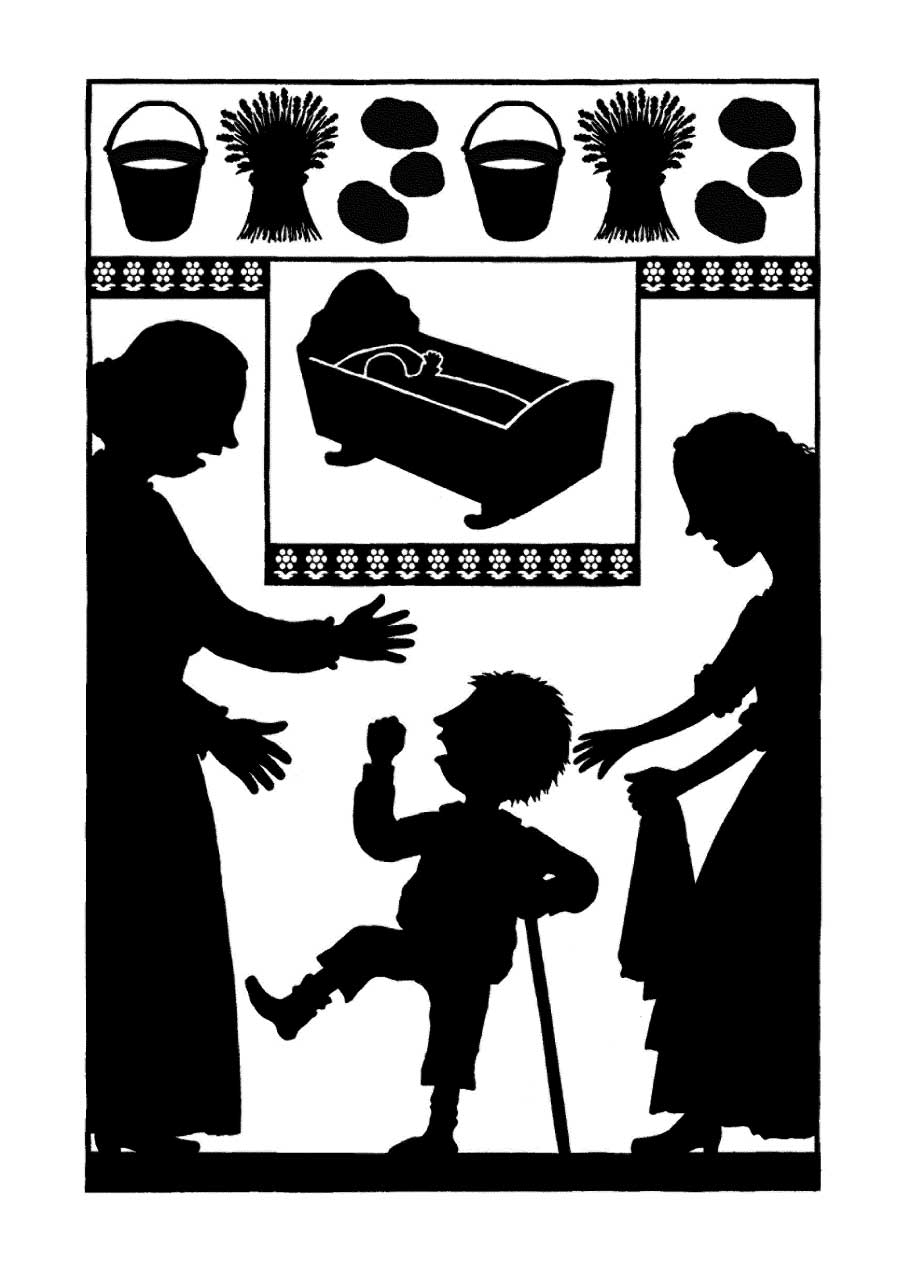

She was outraged when Saul told tales on me.

'You pushed our Saul out of a

tree,

Hetty?' she said,

horrified. She reached for her paddling ladle and I

ran to hide behind Jem.

'It wasn't high up in the tree, Mother, and

she didn't

mean

to,' said Jem, doing his best to

defend me.

Oh, I did so love Jem. But it was no use: I was

well and truly paddled, and Mother forbade all of us

to play in the squirrel house.

Gideon looked mightily relieved, Martha was

indifferent, Jem was clearly sad for me – but I

was so aggravated I stamped and shouted and

screamed at Mother. You can guess the result. I

got paddled all over again, and sent to bed without

any supper.

Mother came and sat beside me as I snuffled in

the dark. 'Now, Hetty, are you sorry for being such

a bad girl?'

'No, I am not sorry.

You

should be sorry for being

a bad mother,' I mumbled beneath my blanket.

Mother had sharper ears than I'd reckoned.

'What

did you say, Hetty?' she said.

Oh no, was I about to get

another

paddling?

My bed started shaking. Mother was making odd

gasping sounds. Had I shocked her so much she was

having a fit, like Ruben in the village after drinking

too much ale?

I peeped above the blanket in terror. Mother was

sitting on the edge of the bed, her hands over her

mouth, splitting her sides with laughter. Oh, the

relief!

'Don't you grin at me, girl!' she spluttered. 'I've

never known such an imp as you. What am I going

to do with you?'

'Paddle me and paddle me, even when I'm a big

girl like Rosie,' I said, laughing too.

But Mother suddenly stopped. She put her arms

round me and hugged me tight. 'Oh, I'm going to

miss you so, little Hetty, even though you're such a

bad, bad girl.'

I am absolutely certain that is what she whispered

into my red hair. I didn't understand. I thought she

meant when I had to attend the village school like

Jem. I didn't dream I was only a temporary member

of Mother's family.

I found it sorely trying when the blissful summer

holidays ended and Jem had to spend all day long

at his lessons. I didn't miss Rosie and Nat and Eliza

one jot, but I missed Jem horrendously. I was left at

home with Martha, who was no fun, and Saul, who

was a sneaking toad, and Gideon, who was a milksop.

They wouldn't play lovely games with me like my

dear Jem. Mother didn't want us under her feet in

the cottage, but neither did she want us toddling

down the village lane and into the woods without

Jem to keep an eye on us, so we were confined to the

front step and our little patch of garden.

If I suggested spitting in the earth and making

mud pies or drawing in the dust with a stick, then

Martha would hang her head dejectedly because

she couldn't see well enough. If I organized a game

of Chase and held Martha's hand, she could run as

fast as me – but then Saul would whine, because

he always came last with his limpy leg. If I tried

a picturing game and pretended a tall oak was a

warty ogre and the grunting pig in the back yard a

mythical monster, Gideon would play on gamely, but

he'd wake screaming in the night. He'd refuse point

blank when told to feed the pig our potato parings,

and whimper to be held whenever Mother took us

for a walk past the oak tree.

I'd hold my breath when Mother comforted then

questioned him. Gideon did not wish to tell tales on

me and get me into trouble. He would press his lips

together when she asked what was ailing him – but

Saul

delighted

in getting me into trouble and told

all sorts of stories to Mother about me, and then of

course I'd get paddled.

Sometimes I decided it was

worth

being paddled

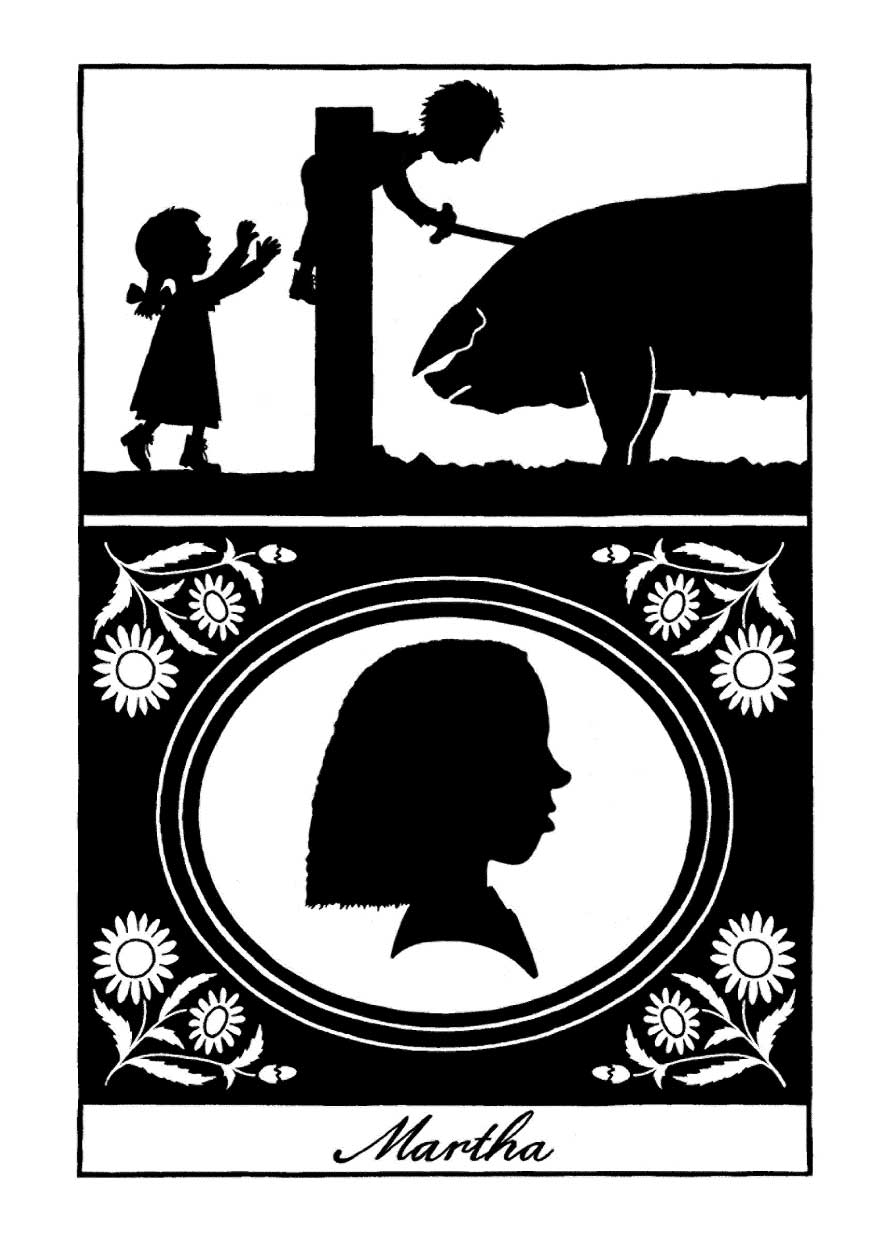

to plague sly Saul. I'd see him lick the jam from

Martha's bread or drop a spider in Gideon's special

mug of milk. I didn't tell stories on him – where was

the fun in that? – but I'd creep up on him unawares

and punish him. Once I spotted him leaning right

over the gate to poke the poor pig with his wooden

crutch, laughing when she squealed. I darted

forward and gave him a shove. Oh, how

he

squealed

when he fell face down in the pigsty. It was so soft

with smelly mud he didn't hurt his poorly leg or his

other leg either. He just hurt his dignity, lying there

bawling, covered in potato peelings and pig poo.

I laughed and laughed and laughed. I even

laughed while I was being paddled.

Jem laughed too when I told him, but he said

I must take care not to be so bad when I went to

school.

'Teacher has a big cane, Hetty, and she swishes

it all day,' he said. 'She hurts much more than

Mother.'

'She swishes

you,

Jem?'

'She swished my friend Janet for chalking her

b

s and

ds

the wrong way round, and when I said it

wasn't fair, Janet had tried and tried to learn, she's

just not very quick, Teacher swished me too and told

me not to answer back.'

'I don't like Teacher,' I said.

I knew my

b

s from my

ds

already because Jem

had taught me. But then I thought of Martha.

'Martha can't write any of her letters,' I said.

'Will Teacher swish

her?'

'I won't let her,' said Jem stoutly.

But Martha didn't go to the village school when

she was five. Mother boiled up a tub of water

one evening and gave Martha her own special

scrub, even though she'd had a washday bath on

Monday. Mother gave her a special creamy mug of

milk for her supper and held her on her lap while

she drank it.

Father gave Martha a ride on his knees.

'This

is the way the ladies ride,'

he sang, jiggling her up

and down while she giggled.

Saul whined that it wasn't fair,

he

wanted a

ride. Gideon said nothing, but he sucked his

thumb and stared while Martha drank

his

milk.

For once I didn't complain. I was too little to under-

stand, but I saw the tears in Mother's eyes, heard

the crack in Father's voice as he sang. I knew

something was wrong – though Martha herself

stayed blissfully unaware.

She went to sleep that night as soon as her head

hit the pillow. I stayed awake, cuddling up to her,

winding a lock of her brown hair round and round

my finger as if I was binding us together.

Mother came and woke us very early.

'Is it time to get up?' I asked sleepily.

'Not for you, Hetty,' said Mother. 'Go back to

sleep.'

It was still so dark I couldn't see her, but I

could tell that she'd been crying again. She gently

coaxed Martha up and led her out of the room.

I turned over into Martha's warm patch and

breathed in her faint bread-and-butter smell,

wondering why Mother had woken her so early. I

decided I should creep out of bed and go and see, but

it still seemed like the middle of the night and I was

so tired . . .

When I woke up again, the sun was shining

through the window. I ran downstairs, calling out

for Martha. She wasn't there. Mother wasn't there

either. Rosie and Eliza were brewing the tea and

stirring porridge.

'Where's Mother? Where's Martha?'

'They've had to go out,' said Rosie. 'Come and sit

down like a good girl, Hetty.'

I didn't want to be a good girl. I wanted Mother

and Martha. My heart was beating hard inside my

chest. I was very frightened, though I didn't quite

know why. I started screaming and couldn't stop,

not even when Eliza bribed me with a dab of butter

and sugar, not even when Rosie slapped my kicking

legs. Jem eventually quietened me, lugging me up

onto his lap and rocking me like a newborn baby,

but he seemed almost as anxious as I was.

Rosie and Nat and Eliza knew something we

didn't. They nudged each other and wouldn't look

us in the eye over our breakfast. Jem questioned

them persistently, I cried, Saul snivelled, and Gideon

didn't get out to the privy in time and wet all down

his legs. We couldn't manage without Mother. She

was always there, as much a part of the cottage as

the roof and the four walls. We were lost without

her. And why had she taken Martha with her?

'You know where Mother's taken her,' said Jem,

standing on the bench so he was eye to eye with

Rosie. 'Tell us!'

'Stop pestering me, Jem. I've got more than

enough to do without you and the babies fuss fuss

fussing. Hetty, if you start that screaming again, I'll

paddle you with Mother's ladle.'

'Don't you dare paddle Hetty,' said Jem. 'She's not

being bad, she's just fearful. She wants Mother.'

'Well, Mother will be back presently,' said Rosie

evasively.

'Why did she go off without saying goodbye? Why

did she take Martha with her?'

'Poor little Martha,' said Rosie, suddenly

softening. Her lip puckered as if she was about to

cry.

'Is Martha poorly?' Jem persisted, but Rosie

wouldn't answer.

When Gideon had been poorly with the croup

last winter, Mother had called in the doctor. He had

looked grave and said Gideon might have to be sent

to hospital.

'Is Martha so poorly she's had to go to

hospital

?'

Jem asked.

He lowered his voice when he said the word. We'd

heard the villagers talking. Hospitals were terrifying

places where doctors cut you open and took out all

your insides.

'She's had to go to the hospital, that's right,'

said Rosie.

Nat sniggered, though even he looked troubled,

his eyes watering as if he was near tears.

Perhaps Martha was very ill, about to die?

But this was all such nonsense. I had cuddled

up to Martha all night long and she hadn't been

poorly at all.

I clung to Jem and he rocked me again. He didn't

go to school that day. He told Rosie he was staying

home to look after us little ones. Rosie tried to make

him go but she sounded half-hearted. She was glad

enough to have him in charge while she scrubbed

the cottage and set the cooking pot bubbling on

the hearth.

Jem played patiently with Saul and Gideon and

me. When the two little boys had a nap after their

soup, Jem took me to the forbidden squirrel house,

trying his best to distract me. I was deeply touched

but it didn't work. No matter how hard I tried to

picture, it stayed a grubby hole in a tree. My mind

was too full picturing Mother and Martha.

Rosie had once won a Sunday school prize, a

book called

Little Elsa's Last Good Deed.

It was a

pretty book, bright blue with gold lettering, and I'd

begged Jem to read it to me. He'd stumbled through

the first few pages until we both got tired. It was

a dull story and Little Elsa was tiresomely

good.

She didn't seem real at all. I leafed through the

whole book, looking for pictures, but they weren't

exciting like the Elephant and the Mandarin and

the Pirate and the Zebra, my favourite pictures in

The Good Child's ABC.

I only liked the last picture,

with Little Elsa lying in bed looking very pale and

poorly, and an angel with curly hair and a shiny hat

flying straight through the window to carry her up

to Heaven.

But now I kept picturing Martha as the ailing

child in some grim hospital, a doctor sawing at her

stomach, an angel at one end, intent on stealing her

away up to Heaven, and Mother down the other end,

hanging onto Martha's ankles.

I sobbed this scenario to Jem and he did his best

to reassure me.

'Mother and Martha will come home safe and

sound, you'll see,' he said. 'In fact I reckon they're

home already, and when Mother finds I've stayed off

school she'll be right angry with me. And if you pipe

up we've been to the squirrel house, we'll both get

a paddling.'

We trailed back home. When we ran into the

kitchen, there was Mother at the table, still stiff

in her Sunday best, bolt upright because she was

wearing her stays, though her head was bent.

Martha was nowhere to be seen.

'Where's Martha, Mother?' Jem asked.

'Martha?' I echoed.

'Martha's . . . gone,' Mother said.

'The angels got her!' I said, starting to cry

again.

'What? No, no, she's not dead, Hetty,' said Mother.

She took a deep breath. 'Where are the others, Saul

and Gideon? Having a nap? Go and get them, Jem. I

might as well tell all of you together. But Jem, wait

– what are you doing at home, young man? Rosie,

why didn't you make him go to school? Oh, never

mind, make me a cup of tea, I'm parched.'

We gathered around Mother, staring at her. I

nudged up close to Jem. Gideon clasped my hand

tight. Saul started snivelling.

'There now, you needn't look so tragic,' said

Mother, sipping her tea. 'Martha's very well. She's

just not going to live with us any more.'

We stared at her, baffled.

'Where

is

she going to live, Mother?' Jem asked.

'She's gone back to the Foundling Hospital,

dearie,' said Mother. 'You were too little to remember

when she came to the family.'

'The hospital! They'll cut her into bits!' I

wailed.

'No, Hetty. It's not that sort of hospital, my lamb.

It's a . . . lovely big home for lots of children who

don't have mothers,' said Mother.

'I remember you telling us about the hospital,'

said Jem. 'That's how we got Martha, then Saul,

and now Gideon and Hetty.' He put his arms round

me, hugging me tightly. 'But why did Martha have

to go back there? You're her mother now.'

Mother's face crumpled. 'I know, my dear. But

I was only her foster mother. I was simply looking

after Martha until she was a big enough girl to go

back to the Foundling Hospital.'

'So when will she come home to us?' Jem asked.

'The Foundling Hospital is her home now, my

dear.'

'But Martha won't be able to manage without us!

She can't see properly, and she's a little slow. She

needs us to help her!' Jem cried.

'She will find some other good kind big child to

help her,' said Mother. 'Now do stop your questioning,

Jem. You're upsetting the little ones.'

She entreated him with her eyes, while Saul

and Gideon and I sniffled by her side. We were too

little and stupid and stunned to work out the obvious

just yet.