Hex (21 page)

There didn't appear to be any choice but to step aboard. Once inside, they found little resemblance to a human-built tram. Instead of seats, there were benches on both sides of the interior; they appeared to have a thin layer of padding upon them but otherwise were bare. Another exit hatch was located on the opposite side of the tram, with a small door in the wall beside it. Next to each of the doors were large vacant areas with recessed rungs in the floor; Rolf guessed that those spaces were reserved for cargo.

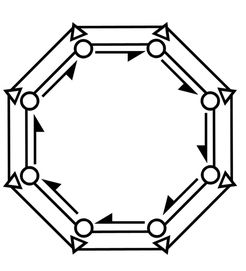

There didn't appear to be a control cab, but on the wall beside the entrance door was a backlit panel. Upon it was displayed what appeared to be a diagram of a hexagon:

Andromeda noted that the node at the top left corner was glowing red. It wasn't hard to guess that the hexagon represented the one they were in and that the illuminated node was the harbor where the

Montero

was docked. But she could only guess what was meant by the rest: the geometric forms along the sides of the hexagon, the clockwise arrows within its inner perimeter, the short arrows pointing away from the other nodes, or the long arrows pointing away from the upper-left and lower-right corners.

Montero

was docked. But she could only guess what was meant by the rest: the geometric forms along the sides of the hexagon, the clockwise arrows within its inner perimeter, the short arrows pointing away from the other nodes, or the long arrows pointing away from the upper-left and lower-right corners.

“A map?” she asked aloud.

“Could be.” Rolf shrugged. “Makes sense. Maybe the arrows show possible directions we can take. But I have no idea what this means.” He pointed to two rows of figures at the bottom of the panel:

“I think I do.” Standing behind them, D'Anguilo smiled knowingly. “Those might be

danui

numbers.” Reaching forward, he pointed to the figure at the right end of the bottom that looked like a crosshatched diamond. “See? Four sides, with vertical and horizontal lines in the middle. Six sides, with no shapes more complex than that, except for a square every now and then.”

danui

numbers.” Reaching forward, he pointed to the figure at the right end of the bottom that looked like a crosshatched diamond. “See? Four sides, with vertical and horizontal lines in the middle. Six sides, with no shapes more complex than that, except for a square every now and then.”

“So?” Melpomene asked.

“Ever looked closely at a picture of a

danui

? Their two forward legs . . . the ones they use most frequently as manipulators . . . have three fingers each. That would indicate that they've developed a base-six numerical system, just as we have a base-ten system because of the number of fingers on our hands. The square must be zero.”

danui

? Their two forward legs . . . the ones they use most frequently as manipulators . . . have three fingers each. That would indicate that they've developed a base-six numerical system, just as we have a base-ten system because of the number of fingers on our hands. The square must be zero.”

Remembering the holo of the

danui

that Ted Harker had shown her, Andromeda had to admit that D'Anguilo might be onto something. “Okay, I'll buy that. But that still doesn't tell us what . . .”

danui

that Ted Harker had shown her, Andromeda had to admit that D'Anguilo might be onto something. “Okay, I'll buy that. But that still doesn't tell us what . . .”

“Wait a minute. I think I got it.” Rolf moved a little closer to the panel. “If this is a map, then the numbers around the edge might tell us which pod is which. And if that's the case”âhe pointed to the two rows of numbersâ“this might be some sort of navigation system.”

D'Anguilo slowly nodded. “Yes . . . yes, I believe you may be right.” He studied the panel for another couple of moments, absently tapping a finger against his lips. “Which would mean that the top row, since it's longer, represents our present coordinates, and the bottom row is our means of entering new coordinates. So the map itself may be our way of getting around within this particular hexagon.”

“Might be,” Andromeda murmured. “Of course, there's only one way to find out.” Raising her hand to the panel, she poised a finger above the top left surface of the hexagon, the one nearest to the red-lighted node. “Brace yourselves. Here goes nothing.”

She pushed the hexagon.

The tram doors slid shut with barely a whisper, and a second later the vehicle began to move. At first, its motion was so slow that they barely noticed, but then it quickly accelerated. Yet the movement was eerily smooth; no bumps or jars, just an effortless plunge down the tunnel, whose rocklike walls raced by the windows so fast that they soon became nothing more than a grey blur. There was only the slightest hum; otherwise, the vehicle was nearly silent.

“Just as I thought,” Rolf said. “Magnetic levitation.”

“Yes,” said D'Anguilo, sitting down on the nearest bench, “but I wonder why they couldn't have put in a pneumatic system instead. They . . .

Hey!

What the hell . . . ?”

Hey!

What the hell . . . ?”

The moment he sat down, the bench's padding started moving beneath him. As if it had a mind of its own, the material reshaped itself to conform to his buttocks. As Andromeda watched, a slender hump rose behind D'Anguilo, becoming a chairback for him to rest against.

“Some sort of smart material,” Rolf said, bending down to examine the bench. “It figures out what's comfortable for you and reshapes itself for your needs.”

“Makes sense.” Andromeda pressed the bench next to the control panel with her fingertips. “Probably designed to accommodate different body forms.”

Rolf nodded as he carefully sat down across from D'Anguilo; he grinned as his seat adapted itself to him. “Efficient . . . just like using maglev rails instead of pneumatic tubes. If these tunnels run through all of Hex, you'd have to maintain high air pressure for billions of tunnels.”

“Sounds plausible.” Andromeda carefully took a seat on the bench, with Melpomene sitting down beside her. Its transformation was unnerving at first, but in a few seconds she was as comfortable as if she were sitting in her seat in

Montero

's command center. “But you've still got to wonder . . . How old is this place, anyway? For something this big and complex, it must have taken thousands of years to build.”

Montero

's command center. “But you've still got to wonder . . . How old is this place, anyway? For something this big and complex, it must have taken thousands of years to build.”

“Uh-huh. At least a couple of thousand years . . . maybe more.” D'Anguilo was quiet for a moment, then he went on. “Y'know, I've been thinking about that, and I wonder if it has anything to do withâ”

He was interrupted by the tram's abruptly moving to the left. Through the windows on the right side of the car, the tunnel walls disappeared for a split second. They caught a brief glimpse of another tunnel, branching away from the one they were in and receding into the distance. Then it vanished as the rock walls closed around them again.

“Must be another line,” Melpomene said. “Maybe leading to another hexagon.”

“Habitat, you mean.” D'Anguilo smiled. “Don't mean to split hairs, but that's what our hosts call them.” He paused, then looked at Andromeda. “Come to think of it . . . Remember what the screen avatar called this place?

Tanaash-haq

?”

Tanaash-haq

?”

“Maybe that's the

danui

word for it,” Andromeda said, although it sounded more like

hjadd

than anything else. “I think I like Hex better. Anyway, what were you about to say?”

danui

word for it,” Andromeda said, although it sounded more like

hjadd

than anything else. “I think I like Hex better. Anyway, what were you about to say?”

“Well, it seems to me that . . .”

Suddenly, the tram began to slow down. Forgetting the discussion, Andromeda gazed through the windows. She couldn't see anything except the tunnel walls, but they appeared to be moving past the tram a little more slowly.

“Looks like we're about to stop.” She carefully rose from the bench, wishing that the

danui

had supplied poles or ceiling straps for riders to hold on to. “Maybe we'll get some answers.”

danui

had supplied poles or ceiling straps for riders to hold on to. “Maybe we'll get some answers.”

Before anyone could reply, light abruptly streamed in through the right-hand windows. The walls had vanished again, and it appeared that the tram had left the tunnel. The vehicle slowly coasted to a halt; a second later, the doors at the front end of the tram slid open. Andromeda looked at the others, then turned to walk forward. Melpomene, Rolf, and D'Anguilo got up from their seats and followed her toward the open doors.

They emerged on a broad platform that was open on three sides, with tiled floors and a high ceiling with luminescent panels. Just past it was an open veranda; a long railing ran along its edge. Andromeda was about to walk over to it when she noticed another control panel, identical to the one aboard the tram, recessed into the platform wall near the tunnel entrance. Pausing to examine it, she noted that the

danui

numbers on its top row had changed slightly. If D'Anguilo was right, and these were coordinates of some sort, it would be wise to copy them for later reference. She was about to pull her datapad from her thigh pocket when Rolf whistled out loud, followed by a startled cry from Melpomene.

danui

numbers on its top row had changed slightly. If D'Anguilo was right, and these were coordinates of some sort, it would be wise to copy them for later reference. She was about to pull her datapad from her thigh pocket when Rolf whistled out loud, followed by a startled cry from Melpomene.

“Oh, my God . . . Skipper, look at this!”

She was standing at the railing, Rolf and D'Anguilo beside her; all three were staring at something below them. Leaving the datapad in her pocket, Andromeda hurried over to join them . . . and felt her heart skip a beat.

Beyond the railing lay a vast valley, larger than any she'd ever seen. With a long range of low mountains sloping down into it from each side, it stretched away without any visible horizon until its farthest end disappeared in atmospheric haze.

The mountainsides and the valley floor were verdant with forests and open plains; grass and trees grew alongside creeks that flowed downhill toward a river that ran straight down the middle of the valley. The air was warm and unbelievably fresh, faintly scented with chlorophyll and wild spices.

Andromeda realized that they were overlooking a biopod from the vantage point of a tram platform. To their right, close to where they were standing, was a mammoth wall; apparently comprised of the same stony material as Hex's outer surfaces, it towered into a blue sky. There appeared to be circular vents evenly spaced within the wall, each large enough to drive the tram through. Air ducts, perhaps?

Before she could study them further, D'Anguilo tapped the back of her hand. “Captain . . . look at the sky.”

It was blue and cloudless, with a bright sun at its zenith, but like none Andromeda had ever seen before in all the worlds she'd visited. Surrounding the sun on all sides were countless hexagonsâvery large near the mountain ridges, incrementally becoming smaller the higher they wentâthat formed a tessellated pattern across the heavens. Gazing upward, Andromeda realized that she was seeing Hex from its inner surface: a vast collection of hexagons, each the same as the one in which she was standing, that stretched to the far side of its captive sun, almost 186 million miles away.

Feeling the light-headed dizziness of vertigo, Andromeda grasped the railing and took slow, deep breaths. Until then, she'd been able to assimilate everything she'd seen since the moment the

Montero

had entered the

danui

system. But this was too much. She suddenly felt very, very small, like an ant standing at the lip of a chasm. Stunned by what she was seeing, she almost missed the insistent electronic chirp coming from her breast pocket.

Montero

had entered the

danui

system. But this was too much. She suddenly felt very, very small, like an ant standing at the lip of a chasm. Stunned by what she was seeing, she almost missed the insistent electronic chirp coming from her breast pocket.

“Skipper?” Melpomene murmured. “The radio . . .”

“Right.” Wrenching her gaze from the weird sky, Andromeda fumbled at the pocket flap until she was able to pull out the small transceiver. She raised its aerial and spoke into its mouth. “Carson here.”

“Montero, Captain.”

Anne's voice was surprisingly clear. Despite the distance between them and the docking node, the ship's VHF signal apparently had no trouble getting through the rock walls.

“Are you okay?”

Anne's voice was surprisingly clear. Despite the distance between them and the docking node, the ship's VHF signal apparently had no trouble getting through the rock walls.

“Are you okay?”

“Fine . . . we're fine.” Andromeda took another deep breath, trying to clear her head. “You and Jason aren't going to believe this place. It's completely . . . I mean . . .”

“Captain . . .”

Anne's voice was hurried, almost impatient.

“I've just heard from Sean. He's alive, but his team is in trouble.”

Anne's voice was hurried, almost impatient.

“I've just heard from Sean. He's alive, but his team is in trouble.”

CHAPTER

FOURTEEN

FOURTEEN

THE SIGNAL SEAN RECEIVED FROM THE

MONTERO

WAS WEAK, but strong enough that he was able to hear his mother's voice.

“Glad to hear that you're still . . .”

she began, then stopped herself.

MONTERO

WAS WEAK, but strong enough that he was able to hear his mother's voice.

“Glad to hear that you're still . . .”

she began, then stopped herself.

Alive,

he thought.

She was about to say, “Glad to hear that you're still alive.”

he thought.

She was about to say, “Glad to hear that you're still alive.”

“Jason tells me that you've crashed,”

she said instead.

“Where are you, do you know?”

she said instead.

“Where are you, do you know?”

“Somewhere on Hex,” Sean replied, as if this explained everything.

Or maybe I should say “in Hex.” Whatever.

“We came in through the roof of the biopod we were investigating and landed in a field not far from its eastern end. I told your first officer the rest . . . He's probably filled you in already. Anyway, we lost our pilot when we crashed, and shortly after that our team leader was killed.”

Or maybe I should say “in Hex.” Whatever.

“We came in through the roof of the biopod we were investigating and landed in a field not far from its eastern end. I told your first officer the rest . . . He's probably filled you in already. Anyway, we lost our pilot when we crashed, and shortly after that our team leader was killed.”

Other books

Dawnbreaker: Legends of the Duskwalker - Book 3 by Posey, Jay

Falling In by Lydia Michaels

Murder Brewed At Home (Microbrewery Mysteries Book 3) by Belle Knudson

The Kissing Bough by Ellis, Madelynne

Mission: Seduction by Candace Havens

Captain Gareth's Mates by Pierce, Cassandra

Awares by Piers Anthony

BREATHE: A Billionaire Romance, Part 3 by Jenn Marlow

Seasons of War by Abraham, Daniel