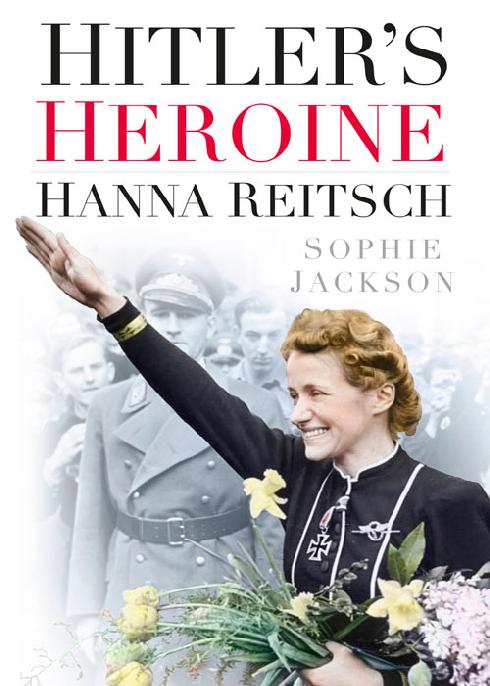

Hitler's Heroine: Hanna Reitsch

Read Hitler's Heroine: Hanna Reitsch Online

Authors: Sophie Jackson

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Transportation, #Aviation, #General

C

ONTENTS

Appendix

1

: Letter from Dr Joseph Goebbels

Appendix

2

: Letter from Magda Goebbels

Appendix

3

: Selected World Records and Awards

Earned by Hanna Reitsch

On the movie screen a petite Hanna Reitsch stares up with naïve wonder at the ranting man she has come to adore and idolise. Hitler rages in fury at Himmler’s betrayal before calming himself and revealing his final (and nonsensical) plan to save Berlin. Eyes wide in admiration, her voice a mere whisper, Hanna looks up. ‘I kneel down to your genius and before the altar of our fatherland,’ she says.

This sycophantic, sickening Hanna – cringe-worthy as she worships the man who has destroyed Germany – is very different from the confident, cocky aviatrix who struts across a different movie screen towards a modified V1 flying bomb. A death trap for previous pilots, the rocket plane stands with its cockpit open awaiting her. ‘There’s no point in your taking unnecessary risks.’ Hanna is told as she strides to the plane, ‘We’ve lost four pilots already.’ ‘I’ve got to find out why these damn crates won’t fly,’ she replies calmly.

The first Hanna appears in a German movie produced in 2004,

Der Untergang

(

Downfall

), played by the actress Anna Thalbach. The second Hanna appears in the British movie

Operation Crossbow

, produced in 1965, played by the German actress Barbara Rütting. Hanna is central to neither of these movies, but performs as part of a side-story. In

Downfall

she barely makes two scenes, in

Operation Crossbow

she features early on and then vanishes once she has tested the V1 successfully (it was

Operation Crossbow

that invented the myth that Hanna test flew V1s to find out why they were missing their targets). Yet the two performances are diametrically opposed to each other. The sycophantic, almost idiotic Hanna against the cool, self-assured, controlled Hanna. More than most characters of the Nazi regime she has become parodied to extremes, either viewed as a stupid girl who believed in Nazism or as a heroine of female flying. Even her name sparks controversy, far more than conversations involving other Nazi followers, such as Hans Baur, Hitler’s pilot. Over and over again Hanna is either derided and scorned or discussed in overly sympathetic and apologetic tones. Neither attitude does her justice, nor do they represent the real Hanna.

Delving through the myths, the propaganda, the hatred and the adoration, the real Hanna surfaces as a pale flicker of light; as a woman who wanted to make her mark at a time when the only people with power were Nazis. She has been called politically naïve; that is perhaps rather generous. Others have labelled her a hardened Nazi, which is perhaps too harsh.

Time has allowed historians to gain perspective. It has enabled more and more academic analysis of the realities behind the horrors of Nazism. Interest is now being paid to what is sometimes called ‘the ordinary Nazi’. The man or woman in the street who believed in National Socialism but not in the extermination of the Jews, who recognised the good Hitler had done for Germany – saving it from poverty, increasing employment, rejuvenating its cities and towns – and found it hard to level this with stories of persecution, cruelty and death. Much was hidden; much was not.

Some years ago, a Russian friend explained her own complicated views on Communism. When she was a child Communism had seemed the greatest thing imaginable. She was from a poor family, yet Communism enabled her to have ballet lessons, nurtured her potential and gave her hope. Only after coming to Britain as an adult did she begin to learn of its dark side. She started to study this ‘other’ Communism and realised that the society she had treasured for the opportunities it had given her was built on such secret cruelty, misery and corruption – it was almost unbelievable. It was impossible to reconcile this view with her own memories. Her happy childhood was now overshadowed by the knowledge that that happiness had been bought by murder and violence.

She is no different to the disillusioned National Socialist who had been spoiled by a system that was now turned on its head and exposed as brutal, desperate and barbarous. Culling people’s perceptions and memories, especially happy ones, is not easy. It is even harder when those people are suffering the shock and poverty of post-war Germany. Should it surprise any of us that those people might hark back to better times, when Hitler first came to power? Germany was torn to shreds, divided by concrete and guns and left to suffer like a wounded animal after 1945. During Hanna’s lifetime that suffering seemed unremitting, she did not live to see the destruction of the Berlin Wall or the flourishing of modern Germany. She saw only devastation – is it so hard to imagine that bitterness and sadness made her think of her glory days when Nazism was young?

In a recent interview the 80-year-old daughter of Rudolph Höss, notorious commandant of Auschwitz, defended her father as ‘the nicest man in the world’ because to her he was, and in comparing that personal image with one paraded to her by the enemy, no matter how true, the reality was impossible to accept.

Hanna had a similar view of Hitler. Always looking for a father figure in her life, she made Hitler her ultimate paternal guide. Affectionate and generous to her, kind and ready to promote her dreams, he was everything a girl could want. Joining this with his post-war image of villainy and corruption was difficult for her. She was disillusioned, hurt and very frightened. She was a girl without a father figure to support her (her own father sadly committed suicide, as did her other male mentor, von Greim). Yet Hanna did deny Hitler. It hurt her and she wished it to remain quiet, but she did tell Americans of his apparent mental collapse and the horror and the shame she felt after learning what had really gone on. She had plans to prevent Nazism resurfacing in Germany, she had hopes to build a brighter future; for this she was smashed down and abused.

Hanna has been harshly treated by many over the years, while her supporters have gone to the opposite extreme, glossing over her mistakes and making the matter worse. Somewhere between the two views lies the real Hanna, the woman who pioneered flying for women, who for many remains the greatest of test pilots. Who spoke her mind and often suffered for it. Hanna did not want pity; she just wanted to fly, that was all she ever wanted. She made bad choices, but no more so than other men and women within the Hitler regime who have been treated with generosity by history.

Why has Hanna drawn so much criticism? Why was she laughed at and shunned? What made her the villain of the piece when her actions within Nazism were very minor? Within Hanna’s story jostle an assortment of characters who had done far more to aid Hitler; from the man who created the V2 rocket, to the pilot who never lost his Nazi leanings. Hanna was no Nazi, but she was no innocent either. The story of the real Hanna is only slowly emerging and must compete with tall tales told about her exploits and cruel words spoken by one-time friends. This volume focuses on the person behind the label of Nazi Aviatrix, and naturally must delve most deeply into her involvement with Hitler during the war. This is not an apology for Hanna, nor a character assassination, but an attempt to portray a complicated person impartially. Along the way Hanna’s story exposes what life was really like for a woman with dreams in the Germany of the 1920s and 1930s.

Wernher von Braun: 1912–77

After the war von Braun gave himself up to the Americans and was taken to the United States under the secret Operation Paperclip. Von Braun worked on the United States Army Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile programme until it was incorporated by NASA. He then served as a director at the Marshall Space Flight Centre and was chief architect of the Saturn V launch vehicle used on the Apollo spacecraft for the moon landing. Despite his former allegiance to the Nazi Party, von Braun was readily adopted by the Americans, largely because of his skills as a rocket scientist. In 1975 he was awarded the National Medal of Science. Von Braun died in 1977 aged 65, from pancreatic cancer, leaving behind his wife Marie Luise (married 1947), two daughters and a son.

Otto Skorzeny: 1908–75

Skorzeny was born in Vienna and joined the Austrian Nazi Party in 1931. He was known for being charismatic and was easily identified by the dramatic duelling scar on his cheek. A bit player in the 1938 Anschluss (when he prevented the Austrian president from being shot by local Nazis), he was already a member of the SA (Sturmabteilung) when he tried to join the Luftwaffe in 1939. Deemed too tall and too old (6ft 4in and aged 31), he instead joined Hitler’s bodyguard regiment, the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler. Skorzeny impressed his superiors not only with his design skills – he had been a civil engineer pre-war – but with his courage and skill in battles on the Eastern Front. In December 1942 he was hit by shrapnel in the back of the head, but refused all medical treatment aside from a few aspirins, a bandage and a glass of schnapps. The wound quickly worsened and he ended up being rushed to Vienna for treatment.

Skorzeny was most famous for his rescue of Mussolini and his part in putting down the rebellion caused by the July 1944 plot on Hitler’s life. In 1947 he was tried as a war criminal for ordering his men to dress in discarded American soldiers’ uniforms during the Battle of the Bulge. The trial descended into farce when former SOE (Special Operations Executive) agent Forest Yeo-Thomas told the court that he and other operatives had worn German uniform to get behind enemy lines. To convict Skorzeny would expose the Allies’ own agents to possible court proceedings. He escaped conviction, but was detained in an internment camp awaiting the decision of a denazification court. In 1948 Skorzeny escaped the camp and went into hiding. He was reported in various countries over the next few years, sometimes working for their intelligence agencies. He helped countless former SS men escape Germany.

He died from lung cancer in Madrid in 1975.

Wolf Hirth: 1900–59

Hirth was a renowned glider and sailplane designer; his brother Hellmuth founded the Hirth Aircraft Engine Manufacturing Company. Hirth was born in Stuttgart and took up gliding as a young man, gaining his licence in 1920. He lost a leg in a motorcycle accident in 1924, but continued to fly with a prosthetic leg. Hirth founded a company with Martin Schempp in 1935, officially becoming a partner in 1938. They manufactured gliders, their first design intended to rival the famous Grunau Baby. During the war the company made assembly parts for the Me 323 and Me 109, along with other aircraft. Immediately post-war the company had to switch to making furniture and wooden components for industry, only switching back to gliders in 1951. In 1956 Hirth was elected president of the German Aero-Club. Three years later he was flying an aerobatic glider when he suffered a heart attack. He died in the subsequent crash.

Heini Dittmar: 1911–60

Dittmar was inspired by his elder brother Edgar to begin gliding and took up an apprenticeship at the German Institute for Gliding (DFS). He went on to build his own glider,

Kondor

, which he used during the Rhön soaring competitions of 1932. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s he both worked with and competed against Hanna Reitsch. He had once been besotted with her, but after she spurned his advances he began to perceive her as a rival. Post-war, Dittmar continued to work as a test pilot. He died while testing a light aircraft of his own design in 1960, when the plane crashed.