H.M.S. Unseen (9 page)

Authors: Patrick Robinson

He lifted his night-vision binoculars and could make out the dark hulk of the submarine out on the buoy, a quarter mile off the starboard beam.

“This is it…” he said. “Lead swimmers…GO.” And he heard a soft splash as the flippers of the first two Islamic Revolutionary Guards hit the dark waters of Plymouth Sound together.

“Okay everyone, let’s go…Six at a time over the port side. I’ll go last…then we’ll regroup and swim in together…50 yards behind Lieutenant Commander Ali and his man. They’re well on their way now.”

Ben pulled down his face mask, fixed his breathing gear, and dropped over the side of

Hedoniste.

He checked with all three group leaders that everyone was safe, then gave the order to swim forward, using flippers, just below the surface. And the nineteen-strong Iranian Naval hit squad began to kick slowly through the water toward HMS

Unseen.

Out in front, Ali Pakravan heard the motor yacht head on up the sound, lights still on full, the noise growing fainter. But he kept swimming: kicking and gliding, no splashing, no arm movement, just the legs, just as they had trained. His colleague, Seaman Kamran Azhari, swam just behind him, the rifle with the night sights clipped to his back.

After seven minutes Ali came to the surface and tried to see the submarine. It took a few moments for him to focus; then he saw her, about 100 yards ahead. In a few more klicks he would be able to see on the fin the white marking S41, the individual identifying mark of the jet-black, 230-foot torpedo and mine-laying patrol submarine, now a part of the Brazilian Navy.

They made their way slowly to the steep, slippery slope of the bow, hidden by its curve, and in the water they prepared the special electromagnetic clamps. Seaman Azhari placed the first two a foot out of the water, then hauled himself up and softly placed two more, three and a half feet higher up

Unseen’

s bow. Next he unclipped the rifle from his back, as the lieutenant commander began to work his way up beside him, moving the magnetic clamps one at a time to give himself purchase.

It took Ali two minutes to reach a point where he could safely lie on the downward curve of the bow. High above he could see the fin, on top of which, he knew, was the night guard. According to Ben, he would just see the man’s head and shoulders above the rail of the bridge. And he would see it very clearly through the night-vision telescopic sight on the rifle.

Ali moved one of the clamps and took up his sniper’s position on the casing. Ben was right. He could see the sentry up there, but the man was standing sideways, hunched against a light rain that was beginning to fall, and made a very difficult target. Ali, the best marksman in the Iranian Navy, was uncertain whether to wait or fire, but he decided that time was a luxury he did not have, so he lined up the crosshairs of the rifle sight with the guard’s left temple. He steadied himself, held his breath, and shot Seaman Carlos Perez dead, from a range of 110 feet. As it made its exit, the snub-nosed bullet blew away the entire right side of the Brazilian’s head. There was no sound save for the familiar soft pop made by a big rifle fitted with a silencer.

With the night guard taken care of, the Iranian lieutenant commander stood up on the casing to signal to the rest of the swimmers it was safe to work their way around to the port side of the submarine. Handing the rifle back to Azhari, he moved along the casing and unclipped the rope ladder he had carried with him. He made it secure, then slid it silently down the hull and into the water. Almost immediately he saw the black-hooded figure of Commander Adnam coming through the water, and Ali Pakravan called out softly in the night, “Here, sir. Right here.”

Ben came up the ladder, still using his breathing gear. Right behind him were two other submariners, both of whom had previously served in the old Iranian Kilos. They moved swiftly to the door at the base of the fin and unclipped it gently. Ben opened it and led the way inside the fin to the top of the conning tower, still undetected. He pulled from his pocket a sealed grenade, a special chlorine grenade, which he prepared and threw straight down the tower hatchway. He waited for what seemed an age after it had gone off with a soft fizzing noise. But it was only a minute, and he climbed down after it, followed by his two henchmen in the full breathing gear.

At the bottom of the tower, in the control room they separated, one man heading forward and one aft, rolling more grenades ahead of them. Ben stayed right where he was, acting as communications number to the men above as they gathered silently on the casing, under the supervision of Lt. Commander Ali Pakravan.

Of the thirty-eight Brazilians aboard, none survived the first two minutes. Those asleep never awoke. Those awake gasped, choked, and quickly died. The massive level of concentrated chlorine released into a confined space, was sudden, silent, and deadly. It took less than ten minutes to ensure no one remained alive.

With the possibility of survivors eliminated, Ben himself started the engines, running them steadily, with the ventilation and battery fans working flat out to clear the hull of the poisonous gas. They tested the atmosphere constantly until almost 0400, when Commander Adnam declared the ship clean so the cold men on the casing could safely come below. There was some nervousness among the team members who did not have full breathing gear, but they all wore small chlorine-proof gas masks and went about the depressing business of dragging the bodies to the torpedo room, where they would be stored, each one zipped tight in a waterproof body bag the team had brought with them. They would be disposed of at the first fueling stop out in the cold Atlantic off Gibraltar. There was, of course, no question of dumping them out into Plymouth Sound.

By 0400 Commander Adnam had located the ship’s weekly Practice Program and the daily signal log. These two items had told him what to expect. Even the names of the four British training staff. The dreaded Sea Riders, he remembered, were due to come back on board at 0755 that morning. Same team all week. He noted that the Brazilians were a little behind where they should be at this stage of the proceedings. The previous day the crew had been practicing routine snorkeling drills, starting, running, and stopping the diesels while submerged.

“Should have finished that last week,” he murmured, as he turned the pages, trying to find out what they were scheduled to do today. “Good job old MacLean’s not training them. He’d have made them walk the plank by now.”

As he had guessed,

Unseen

was due to sail at 0800. This was listed alongside the Exercise Area, Stop Time, and Type of Exercise. The day’s activities were simply listed as INDEX—Independent Exercises. But there were some scribbled notes in the margins that told him they had been scheduled for emergency maneuvers: matters such as the avoidance of oncoming shipping; plane breakdowns; steering failure; failure of the systems that govern seawater, electronics, hydraulics, mechanics. Breakdown drills. Fire drills. Flooding drills…etc., etc. But there was also the most blinding bit of luck—the submarine was to stay out overnight, getting some much-needed practice on special drills, in particular night snorkeling

Ben read the Orders slowly and carefully, then located the previous day’s Next-of-Kin signal, the one every submarine captain sends to his shore-based headquarters immediately before departure. This details all changes to the crew list in the NOK book held ashore; the final update, ensuring accurate names and addresses of the next of kin of

every

man aboard, just in case the submarine should disappear.

At 0500 he called a short briefing for his officers, while the rest of the team continued to familiarize themselves with their specialist areas of the ship. Of course, everything was more real than it had been in the Bandar Abbas model, where they had practiced so intensely for many weeks. But, with very few exceptions, every switch, valve, and keyboard was exactly where it had been in the model; the precious data from the big computer in Barrow-in-Furness had taken care of that.

“Gentlemen,” said the commander, “I am sorry for the delay, but I have been trying to read up on procedures. Our sailing time is, as planned, 0800, three hours from now. I have the Next-of-Kin update, and the Squadron Standing Orders. At about 0755 we are expecting four Royal Navy Sea Riders to arrive from the dockyard to supervise the day’s exercises. And we will take care of them as planned. We will allow them to arrive safely and go below. Lieutenant Commander Pakravan, well-done tonight. You and Seaman Azhari did an outstanding and difficult job. I know I can leave you to silence the Sea Riders as soon as they come below.

“The only major change to our plan is that I intend to send

Unseen’

s diving signal to cover today and tomorrow’s program, because she’s not due back until tomorrow evening. However, we must send in a Check Report every twelve hours because this ship is still in Safety Workup. I intend to comply with all of the external procedures when we depart, and it is vital that we make no errors. I also intend to

walk

out of Plymouth Sound with this ship, not run. When we leave here I do not want one shred of suspicion left behind us. That way we have many hours to get free. And once we are free, they’ll never find us.”

Like all of the Iranians, Lt. Commander Arash Rajavi listened carefully to the intensive two-hour training program they all faced. And he tried to stay calm. But it was hard to cast from his mind the overwhelming magnitude of their crime. There they were, sitting bang in the middle of the historic harbor of Sir Francis Drake, the very cradle of the Royal Navy, having

stolen

one of their submarines and killed all of the crew. Three hours from now Commander Adnam was planning summarily to murder two British officers and probably a couple of petty officers.

My God!

he thought.

If we are caught, they will execute every last one of us.

But he fought back his fear and his natural instinct to escape from there at all costs as he listened to the cool, measured words of his leader. Not for the first time, Lieutenant Commander Rajavi decided that Benjamin Adnam was, without doubt, the most cold-blooded man he had ever met.

Two hours later, neatly dressed in Brazilian Naval uniforms, four hands, in company with a young officer, waited on the casing for the arrival of the Sea Riders. They spotted them through the cabin windows of the harbor launch, speeding down the well-marked channel west of Drake’s Island, toward

Unseen

at 0750. Two more officers, plus a lookout, were on the bridge, all in Brazilian uniforms. Five minutes later the launch was alongside, and the young officer on the casing saluted, wishing the Royal Navy men “Good Morning” in an Iranian accent which Ben hoped would be assumed to be Brazilian.

The launch headed back to the dockyard, and one by one the four Royal Navy men came on board, making for the open hatch on top of the casing. There was an 8-foot steel ladder inside, and the leader, Chief Petty Officer Tom Sowerby, made his way expertly downward, his final steps on this earth. As his right foot hit the ground three of the Iranians grabbed him, with a hand clamped tight over his mouth to stop him crying out as Ali’s knife cleaved into his heart. Lt. Commander Bill Colley, next on the ladder, never realized what was happening below until it happened to him as well.

Eight minutes later, all four of the Royal Navy men had joined the pile of zipped-up bodies in the torpedo room. It was 0759, and Commander Adnam was preparing to leave British waters.

At 0800 sharp, he ordered the Brazilian ensign hoisted on top of the fin. The diesel generators were still running sweetly as they slipped the buoy, and Ben ordered, “Half astern,

”

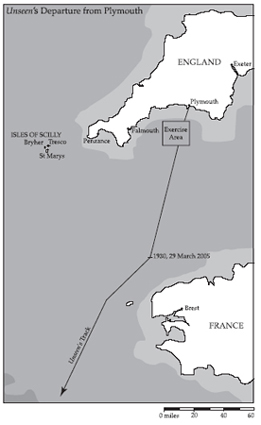

then “Half ahead” as he turned HMS

Unseen

away from Plymouth, making coolly for the western end of the breakwater, and freedom. No one, in all of the great sprawling Royal Navy base, had the remotest idea that anything was other than normal.

The men accompanying Lieutenant Commander Rajavi on the bridge were surprised at the sight of Rame Head as they ran fair down the channel, keeping the big red buoys to starboard. The headland, steep-sided, solid rock, no trees, with a small chapel on top, looked even higher by day, visible for almost 20 miles. Ben Adnam’s engineering officer had the big electric motor running steadily, with the diesels working to provide the power.

Below in the control center, the CO studied the operations area where

Unseen

was scheduled to work that day, and headed for the northeast corner of the “square,” a couple of miles west of the Eddystone Lighthouse. There was almost 200 feet of water under the keel, and, with all signals now correctly sent to home base, he ordered the submarine to dive. The great black hull slid down beneath the cold gray waves, leaving behind a mystery that would rival that of the

Marie Celeste,

and which would last for many, many months.

Commander Adnam was in perfect position. He was in precisely the area he was supposed to be. He wanted to test his team in some under way drills in precisely the same way the Sea Riders would have been testing the Brazilians. In the following few hours he worked the Iranians through the electrical and mechanical systems, the sonar, the radar, the ESM, the communications, the trimming and ballasting, the hydraulics and air systems, even the domestic water and sewage systems. He checked the periscopes and low-light aids, sometimes running easily at nine knots, occasionally stopping in the water to give his Officer of the Watch experience at trimming this new and strange submarine. More than half of the time was spent snorkeling, making certain the ship’s battery was well topped-up. Sometimes the commander offered quiet advice to the younger men, sometimes he pushed them harder. But there was never an edge to his voice. He was always conscious that a tired crew might make mistakes, but not so many as a tired and frightened crew.