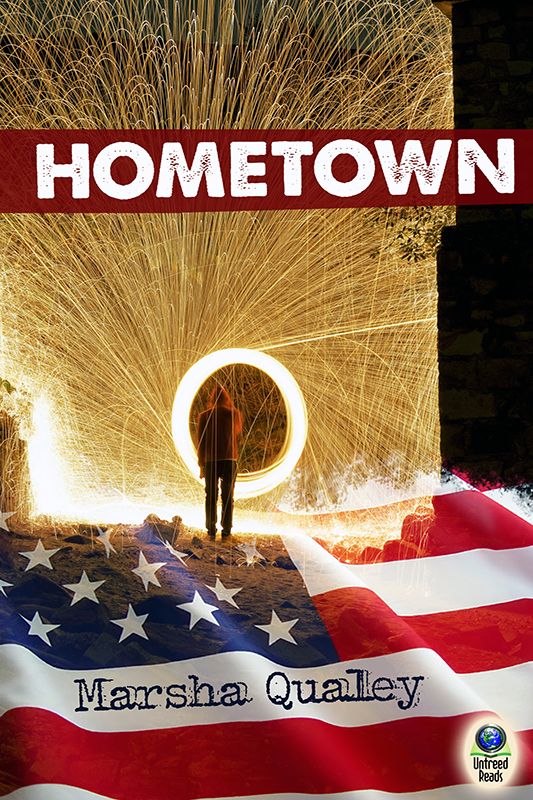

Hometown

Hometown

By Marsha Qualey

Copyright 2014 by Marsha Qualey

Cover Copyright 2014 by Untreed Reads Publishing

Cover Design by Ginny Glass

The author is hereby established as the sole holder of the copyright. Either the publisher (Untreed Reads) or author may enforce copyrights to the fullest extent.

Previously published in print, 1995.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to your ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

This is a work of fiction. The characters, dialogue and events in this book are wholly fictional, and any resemblance to companies and actual persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Also by Marsha Qualey and Untreed Reads Publishing

Thin Ice

Venom and the River: A Novel of Pepin

One Night

Close To a Killer

Hometown

Marsha Qualey

I

Departure

Pyroball

—

They never should have let the kid play. He was too little and new. He hadn’t been hanging around long enough to get the feel of the game, to understand the timing and learn the moves.

The kid held the tennis ball too long. Worse, he gave it a squeeze, and a trickle of alcohol slid down his wrist. The flame followed, igniting the sleeve of his raggedy shirt.

He dropped the ball and howled. A girl screamed.

A bigger flame now. The kid shrieked.

Border Baker slipped out of his leather jacket and ran to the burning boy. “Sit down,” he barked. The kid dropped to his knees, and Border covered the arm with the jacket, wrapped it tight until the flame was smothered.

The air stank.

Others crowded around them. The kid fell over and Border held him. “Kid, do you live with your family?” The boy nodded. “Someone call them. Who knows his family?”

No one did.

He looked at the boy and said, “Passed out.” He rocked the boy. “You’ll be okay, kid. It’ll be okay.”

They carried him to the emergency room at Presbyterian. Ten blocks with dead weight. The boy groaned, but didn’t come around. Border had an arm under the kid’s back and a hold of his good hand. The burned one flopped loose. No one would touch it.

Sunday morning, 2

a

.

m

.,

and it was slow in the E.R. The Saturday night drunks and brawlers had been sent home. Two women with babies, a man with an ice pack on his face, no other emergencies. The admission clerk rolled her head away from the TV and said, “Yeah, kids?”

“He’s been burned,” said Border. The clerk saw the hand and shouted. Suddenly the room was filled with adults doing their jobs.

Riley handed Border the leather jacket, murmured something, and all the kids fled. Border shrugged and found a chair. He was tired and he didn’t mind answering questions. Hospitals, there were always questions. He’d even talk to the cops, if they came. It wasn’t

his

tennis ball,

his

alcohol,

his

game, he could say. Yes, Officer, he knew they shouldn’t play in the arroyos. Please, Officer, he’d only been there to find Riley, who owed him ten bucks.

“Riley, hey!” Border called, remembering. He twisted around. No kids anywhere. Ten-dollar loan to Riley. Dumb. Dumb as playing pyroball.

The clerk came with the questions. Border told what he knew, which was next to nothing.

“His parents? His address?”

Border shrugged.

“Then we’ll just wait until he’s awake,” said the clerk. She went back to watching television, switching channels until she found news. A woman with incredible hair was interviewing generals in Saudi Arabia. The generals looked concerned. Manly. The reporter looked small. Border found a Tootsie Roll in his jacket pocket, unwrapped it, and popped it into his mouth. He turned the leather jacket around in his hands, checking for damage. The silk lining was scorched, no worse.

Border zipped himself into the jacket, slunk down, and let the soft leather push up around his ears. He was in no hurry to leave. Anyway, where would he go? His dad might not even be at the apartment. “Let’s leave at noon,” the old man had said. “Please,” Border had replied. “You’re dragging me off to live in a strange place. Just let me have a couple more days with my friends.” His father had been firm. “It’s a long drive to Minnesota, and I want to have time to settle in before I start the new job.” Border had walked out then, claiming he had to find Riley and the ten dollars.

Maybe he

had

left at noon, almost two days ago. Maybe this time he had shrugged off his son’s disappearance into the streets of Albuquerque and left at noon. But he’d have had to make a phone call first. A call to Border’s mother in Santa Fe.

“It’s your problem this time. I give up. He’s sixteen and doesn’t think he needs a father. Fine. When you find him, you keep him.” Maybe he had said that this time.

The calm and warmth of the hospital felt good. Border had spent Friday night at Dayton’s apartment, a place where kids could always crash. But it had snowed—the first really cold night of the winter—so there were a lot of people at Dayton’s. The music never stopped. Celeste was there with her baby. It cried, and she wanted to talk, anyone would do. With all that going on Border hadn’t slept. Tonight he hadn’t gone back, just sat in a diner with coffee and toast, asking for Riley anytime he saw someone he knew.

Someone did come in who knew about Riley. Said there was a pyroball game going on up in Lobos Arroyo. Border bought the guy coffee and left, walked a mile in the cold. Ten dollars, after all.

Border tapped his fingers along his thighs. Wished he had his recorder. Stupid, he’d left without it. Left it on top of his duffle bag. He knew then his fate was sealed. He’d have to find his father. Without the instrument, he had no way to earn a living. “You win, Dad,” he murmured. “I lose.” Defeated. Resigned. Tired.

He slept for hours in the waiting room chair and woke to find his father sitting next to him.

No smile? “Hey, Dad. Are we still leaving at noon?”

“If you’re going to run and hide, you need to be smarter about it than to land in a hospital.”

True enough. The old man was a nurse, an anesthetist, with lots of medical friends.

“Did someone around here call you?”

“I called. My kid disappears for two days, I check the hospitals. They told me you brought in a burned boy. One of your friends? Someone I know?”

“Just a kid.”

His father tugged on Border’s arm and they both rose. “I don’t know why you all play that game,” he said. “I don’t know why the cops haven’t stopped it, why they let it go on.”

Border looked at the TV screen. Fighter jets were lined up on a Saudi Arabian tarmac. Lots of stuff was going on. Who knew why?

Departure

—

Stalling tactic. “Maybe I should call Mom and say goodbye.”

“You’ve said good-bye. And I doubt if you could reach her. When I was trying to find you, I called her. She said that the protest had been pushed up to this morning. She was scheduled to be in the first wave. It’s almost sunrise. She’s probably been arrested by now.”

“Does she have bail money? She might need bail money, Dad.”

“Not from me. Not this time.”

Son and father walked to their car. Border wanted to ask his father to drive to Santa Fe, just an hour north, hardly out of the way. He wanted to drive by the capitol and see the protesters chained to the benches, see the bodies laid across the street. See his mother, if she hadn’t already been hauled to jail.

He’d been at her apartment the night final protest plans had been voted upon. It had been packed, twenty adults screaming at each other because they were mad at the government. No guns for oil! We must be heard! Border had served tea and cookies, then, when business was done, agreed to play recorder for the remaining people. Seven minutes of Mozart. The protesters were old friends, sort of; his family had only lived in New Mexico three years. But they were like the friends they’d had everywhere. Fort Collins, Missoula, Detroit, Winnipeg, Toronto, though that was so long ago he couldn’t remember.

Always friends in the apartment, on the phone, on the sofa.

When his mother and older half sister had moved to Santa Fe, he realized that most of the friends must have been theirs because the apartment became so quiet and empty.

He liked the quiet. He practiced more often, tackled Brahms. They bought a television.

Maybe she’d be on the news. “Dad, let’s stay one more night.”

“Where? I’ve turned in the apartment keys.”

Border grinned. “Are we homeless?”

“No,” his father responded sternly. “We have a home waiting in Minnesota.”

The old man was willing to stay longer, just for breakfast. They both ordered big and ate it all. Border got seconds and coffee to go. Slipping on ice, he spilled half the cup before they were back in the car, then sloshed some on his pants as he set the cup on the dash. An ominous start, he said to his dad, who said nothing at all.

They reached the ramp onto the highway. Just before his father accelerated, Border looked back for a last glimpse of Albuquerque, his city. Out of the corner of his eye he glimpsed green hair come out of an apartment building.

A shout lodged in his throat: Dana! But no, of course not. His sister hadn’t been in town for weeks and anyway, she was in South Carolina, visiting her father’s family.

The city was slipping away. Beyond the highway, a child playing alone in the early morning hurled wet sand across a playground. Great brown gobs soared and fell, then hit the ground, scattering on impact.

Storm—

For the first forty miles they listened to the radio, Border’s father impatiently switching stations. War or football, that’s all there was. Less than two weeks remained before the UN’s ultimatum to Iraq expired. Three weeks until the Super Bowl. Announcers for either were deadly serious.

“Four teams prepare for today’s battles; only two will survive.”

“Tension is building among the troops waiting here at the Saudi border.”

Border smiled. He liked hearing his name in the news. And for half a year he’d heard it plenty and seen it often in headlines.

Iraqi army crosses Kuwait’s border.

Saddam’s guns aimed at Saudi border.

Border towns wait in fear.

His favorite, though, was a headline his mother had clipped from the Santa Fe paper and sent without any added comment the day after hearing about a failed history test.

Latest poll: Border violation unacceptable.

*

Border drove through most of the night while his father slept. Progress was slow; the old car refused to go over sixty. They switched drivers somewhere in Oklahoma, and he slept for an hour before waking up to daylight and the flattest country he’d ever seen, flatter even than Manitoba.

They cleaned up at a rest stop. Border debated changing shirts, sniffed himself, decided it wouldn’t be worth it.

South of Kansas City, snow started falling. Random flakes at first, then steadier and heavier. The sky behind them was a dark wall of clouds. Wind butted their car insistently.

North of Kansas City, the highway became snow-covered except for two dark tracks in the right lane.

They hadn’t said much at all the entire trip and now they spoke less. A grunt from the father, soft music from the son as he hummed and tapped his fingers along his thighs in a deliberate pattern, recorder notes, a Telemann minuet.