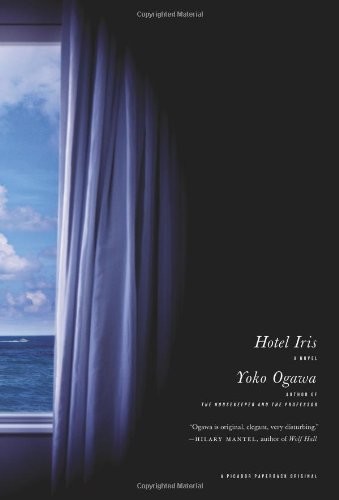

Hotel Iris

H O T E L

I R I S

Yoko Ogawa

TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE BY

STEPHEN SNYDER

Harvill Secker

London

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781407087481

Published by Harvill Secker 2010

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © Yoko Ogawa 1996

English translation copyright © Stephen Snyder 2010

English translation rights arranged with Yoko Ogawa through Japan Foreign-Rights Centre / Anna Stein

Yoko Ogawa has asserted her right under the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published with the title

Hotel Iris

in 1996 by Gakken, Tokyo

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by

Harvill Secker

Random House

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road

London SW1V 2SA

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at:

www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781846554032

The Random House Group Limited supports The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading international forest certification organisation. All our titles that are printed on Greenpeace approved FSC certified paper carry the FSC logo. Our paper procurement policy can be found at

www.rbooks.co.uk/environment

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

CPI Mackays, Chatham, ME5 8TD

Also by Yoko Ogawa

The Diving Pool

The Housekeeper and the Professor

O N E

He first came to the Iris one day just before the beginning of the summer season. The rain had been falling since dawn. It grew heavier at dusk, and the sea was rough and gray. A gust blew open the door, and rain soaked the carpet in the lobby. The shopkeepers in the neighborhood had turned off their neon signs along the empty streets. A car passed from time to time, its headlights shining through the raindrops.

I was about to lock up the cash register and turn out the lights in the lobby, when I heard something heavy hitting the floor above, followed by a woman’s scream. It was a very long scream—so long that I started to wonder before it ended whether she wasn’t laughing instead.

“Filthy pervert!” The scream stopped at last, and a woman came flying out of Room 202. “You disgusting old man!” She caught her foot on a seam in the carpet and fell on the landing,

but she went on hurling insults at the door of the room. “What do you think I am? You’re not fit to be with a woman like me! Scumbag! Impotent bastard!”

She was obviously a prostitute—even I could tell that much—and no longer young. Frizzy hair hung at her wrinkled neck, and thick, shiny lipstick had smeared onto her cheeks. Her mascara had run, and her left breast hung out of her blouse where the buttons had come undone. Pale pink thighs protruded from a short skirt, marked in places with red scratches. She had lost one of her cheap plastic high heels.

Her insults stopped for a moment, but then a pillow flew out of the room, hitting her square in the face, and the screaming started all over again. The pillow lay on the landing, smeared with lipstick. Roused by the noise, a few guests had now gathered in the hall in their pajamas. My mother appeared from our apartment in the back.

“You pervert! Creep! You’re not fit for a cat in heat.” The prostitute’s voice, ragged and hoarse with tears, dissolved into coughs and sobs as one object after another came flying out of the room: a hanger, a crumpled bra, the missing high heel, a handbag. The handbag fell open, and the contents scattered across the hall. The woman clearly wanted to escape down the stairs, but she was too flustered to get to her feet—or perhaps she had turned an ankle.

“Shut up! We’re trying to sleep!” one of the guests shouted from down the hall, and the others started complaining all at once. Only Room 202 was perfectly silent. I couldn’t see the occupant, and he hadn’t said a word. The only signs of his

existence were the woman’s horrible glare and the objects flying out at her.

“I’m sorry,” my mother interrupted, coming to the bottom of the stairs, “but I’m afraid I’m going to have to ask you to leave.”

“You don’t have to tell me!” the woman shouted. “I’m going!”

“I’ll be calling the police, of course,” Mother said, to no one in particular. “But please,” she added, turning to the other guests, “don’t think anything more about it. Good night. I’m sorry you’ve been disturbed. … And as for you,” she went on, calling up to the man in Room 202, “you’re going to have to pay for all of this, and I don’t mean just the price of the room.” On her way to the second floor, Mother passed the woman. She had scraped the contents back into the bag and was stumbling down the stairs without even bothering to button her blouse. One of the guests whistled at her exposed breast.

“Just a minute, you,” Mother said into the darkened room and to the prostitute on the stairs. “Who’s going to pay? You can’t just slip out after all this fuss.” Mother’s first concern was always the money. The prostitute ignored her, but at that moment a voice rang out from above.

“Shut up, whore.” The voice seemed to pass through us, silencing the whole hotel. It was powerful and deep, but with no trace of anger. Instead, it was almost serene, like a hypnotic note from a cello or a horn.

I turned to find the man standing on the landing. He was

past middle age, on the verge of being old. He wore a pressed white shirt and dark brown pants, and he held a jacket of the same material in his hand. Though the woman was completely disheveled, he was not even breathing heavily. Nor did he seem particularly embarrassed. Only the few tangled hairs on his forehead suggested that anything was out of the ordinary.

It occurred to me that I had never heard such a beautiful voice giving an order. It was calm and imposing, with no hint of indecision. Even the word “whore” was somehow appealing.

“Shut up, whore.” I tried repeating it to myself, hoping I might hear him say the word again. But he said nothing more.

The woman turned and spat at him pathetically before walking out the door. The spray of saliva fell on the carpet.

“You’ll have to pay for everything,” Mother said, rounding on the man once more. “The cleaning, and something extra for the trouble you’ve caused. And you are not welcome here again, understand? I don’t take customers who make trouble with women. Don’t you forget it.”

The other guests went slowly back to their rooms. The man slipped on his jacket and walked down the stairs in silence, never raising his eyes. He pulled two bills from his pocket and tossed them on the counter. They lay there for a moment, crumpled pathetically, before I took them and smoothed them carefully on my palm. They were slightly

warm from the man’s body. He walked out into the rain without so much as a glance in my direction.

I’ve always wondered how our inn came to be called the Hotel Iris. All the other hotels in the area have names that have to do with the sea.

“It’s a beautiful flower, and the name of the rainbow goddess in Greek mythology. Pretty stylish, don’t you think?” When I was a child, my grandfather had offered this explanation.

Still, there were no irises blooming in the courtyard, no roses or pansies or daffodils either. Just an overgrown dogwood, a zelkova tree, and some weeds. There was a small fountain made of bricks, but it hadn’t worked in a long time. In the middle of the fountain stood a plaster statue of a curly-haired boy in a long coat. His head was cocked to one side and he was playing the harp, but his face had no lips or eyelids and was covered with bird droppings. I wondered where my grandfather had come up with the story about the goddess, since no one in our family knew anything about literature, let alone Greek mythology.

I tried to imagine the goddess—slender neck, full breasts, eyes staring off into the distance. And a robe with all the colors of the rainbow. One shake of that robe could cast a spell of beauty over the whole earth. I always thought that if the goddess of the rainbow would come to our hotel for even

a few minutes, the boy in the fountain would learn to play happy tunes on his harp.

The

R

in

IRIS

on the sign on the roof had come loose and was tilted a bit to the right. It looked a little silly, but also slightly sinister. In any event, no one ever thought to fix it.

Our family lived in the three dark rooms behind the front desk. When I was born, there were five of us. My grandmother was the first to go, but that was while I was still a baby so I don’t remember it. She died of a bad heart, I think. Next was my father. I was eight then, so I remember everything.

And then it was grandfather’s turn. He died two years ago. He got cancer in his pancreas or his gallbladder—somewhere in his stomach—and it spread to his bones and his lungs and his brain. He suffered for almost six months, but he died in his own bed. We had given him one of the good mattresses, from a guest room, but only after it had broken a spring. Whenever he turned over in bed, it sounded like someone stepping on a frog.

My job was to sterilize the tube that came out of his right side and to empty the fluid that had collected in the bag at the end of it. Mother made me do this every day after school, though I was afraid to touch the tube. If you didn’t do it right, the tube fell out of his side, and I always imagined that his organs were going to spurt from the hole it left. The liquid in the bag was a beautiful shade of yellow, and I often wondered why something so pretty was hidden away inside the body. I emptied it into the fountain in the courtyard, wetting the toes of the harp-playing boy.

Grandfather suffered all the time, but the hour just before dawn was especially bad. His groans echoed in the dark, mingling with the croaking of the mattress. We kept the shutters closed, but the guests still complained about the noise.

“I’m terribly sorry,” Mother would tell them, her voice sickly sweet, her pen tapping nervously on the counter. “All those cats seem to be in heat at the same time.”

We kept the hotel open even on the day grandfather died. It was off-season and we should have been nearly empty, but for some reason a women’s choir had booked several rooms. Strains of “Edelweiss” or “When It’s Lamp-Lighting Time in the Valley” or “Lorelei” filled the pauses in the funeral prayers. The priest pretended not to hear and went on with the service, eyes fixed on the floor in front of him. The woman who owned the dress shop—an old drinking friend of Grandfather’s—sobbed at one point as a soprano in the choir hit a high note and together it sounded almost like harmony. The ladies were singing in every corner of the hotel—in the bath, in the dining room, out on the veranda—and their voices fell like a shroud over Grandfather’s body. But the goddess of the rainbow never came to shake her robe for him.