How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (52 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

McGee’s next move, whatever his mental and physical state, proved to be his most far-reaching and lucrative, and the one with which he is for ever fixed in the public imagination.

While out one night with his sister in Glasgow, McGee offered a record deal on the spot to the band they by chance had just seen play – Oasis. During the glory years of Britpop – Downing Street, the Met Bar, Knebworth – the Oasis and Creation story was a key media narrative for the buoyancy of the times. Away from the PR, industry insiders quietly whispered that all may not have been as it seemed.

‘There’s so many urban myths about them,’ says Abbott. ‘What is true is that McGee did see them in King Tuts. McGee phoned us up at 5 a.m., to rant about them full-on down the phone.’ Much to the delight of Sony, McGee had come through with the kind of act that would benefit from their system. Oasis and Creation bonded on the band’s first visit to the bunker, while the band’s manager, Marcus Russell, had decided to evaluate the situation at his own pace. In a deal that still has different interpretations from its various signatories, Oasis signed with Creation in the UK and with Sony for the rest of the world.

‘Sony signed the Creation deal for Primal Scream, not Oasis,’

says Abbott. ‘What Sony wanted was

Screamadelica 2

– they struck gold.’

‘Sony were all over Oasis,’ says McGee. ‘Apparently, if you’d walked past them in the street, you’d signed Oasis. I must have met twenty-five people who’ve signed that band. This guy worked for me in 1987 for three months, then he fucked off to Sony, and then two or three years ago, at the height of

X-Factor

, he’s one of the judges, a huge star in Australia. He’s the guy behind Oasis. I don’t think he’s ever met Liam.’

As the word of mouth began to build around Creation’s latest signing, an air of invincibility in the band was palpable. Unlike Ride, the House of Love or many of the label’s previous

non-Glaswegian

signings, Oasis were from a similar background to McGee and Abbott. Noel Gallagher in particular had also been through the shared experience of Ecstasy and the club epiphanies through which McGee and Abbott had first become close. Abbott too was convinced Oasis were going to be the band that re-educated the dance music audience about rock ’n’ roll.

‘It was a fluke, it was a complete fluke,’ says McGee. ‘Oasis summed it up to me when we first met. It was, “Let’s fucking have it,” big time, that was the vibe of them and that was the vibe of me and in the middle of it all I went into drug rehabilitation.’

As the momentum around Oasis gathered at a pace no one at Creation, or in the rest of the music industry, had experienced for a generation, McGee’s exhaustion, brought on by years of partying, finally caught up with him. On a trip to LA he was hospitalised and a long painful, process of recovery began.

While McGee withdrew from the office, Creation was left in the hands of Abbott and Green. To their relief they realised that Marcus Russell was a manager with an equilibrium that avoided the growing circus around his charges and he was thinking in the long term.

‘With Oasis the press and radio took it all,’ says Kyllo, ‘and the band’s management were very professional. It made us realise we had to raise our game and be professional ourselves.’ Another factor ensured that the workload around Oasis remained high and of a sufficient quality. ‘There was a guy called Mark Taylor,’ says Kyllo. ‘He’d been working for Sony and he was put in on Sony’s payroll to protect their asset.’

Aware that he had signed the biggest band of his career McGee, despite his mental fragility, was still calling the office. ‘He would phone up when he wanted to try and run the business,’ says Abbott. ‘I just said, quite categorically, “Alan, look, you’re not very well, mate. Don’t worry about it, when you’re ready just come back.”’

Abbott had managed to ostracise himself from some of his colleagues at Westgate Street but he was firmly part of the Oasis and Primal Scream camps. However much he divided the office, he was given credit by Oasis for running the campaign of

Definitely Maybe

and was sufficiently embedded in the eye of the storm surrounding their ascendency to have written a book about his experiences and appear on the sleeve of the single ‘Cigarettes and Alcohol’.

To James Kyllo, who was less involved in Oasis and has a naturally stoical countenance, it was harder to quantify what contribution Abbott had made. ‘The only marketing activity I was ever aware of Tim Abbott doing,’ he says, ‘was taking some store buyers to a strip club.’

Whatever the claims and counter-claims to the authorship of Oasis’s success, a phenomenon that was almost uncontrollable, McGee and Abbott’s relationship came to an abrupt and unhappy end. During negotiations over the Sony deal, Abbott was given the impression that he would be accredited shares in Creation. The rapidity of Oasis’s success and McGee’s simultaneous

withdrawal meant the matter was left unresolved.

Abbott brought the subject of shares up in a phone call with McGee that highlighted the different pace at which the two of them were now operating. ‘He rang up in the middle of it all and I said, “Dude, I’m trying to fucking MD your company,”’ says Abbott. ‘“We’ve got this band going through the ceiling, everything’s hunky-dory, you get yourself well, and by the way have you transferred those shares we were talking about yet?” … End of … phone down … next day, came into work and Dick went, “You’re in trouble. Alan told me that he can no longer work with you.”’

Abbott was retained by Oasis as a consultant and was responsible for shepherding Noel Gallagher back into the fold having quit the group during the first of one its many fracas in the States. ‘It was fucking fantastic, those two couple of years,’ says Abbott. ‘It was quite difficult as well, delivering all that and then getting ripped off.’

Mark Bowen was an old friend of the Boo Radleys’ Martin Carr, who would shortly be joining the Creation staff. He and Carr, along with, it seemed, the rest of the music industry, had crammed into the Water Rats in King’s Cross to see Oasis’s first official London engagement.

‘I went to the Water Rats with Martin and it was really busy and I thought, can I even be bothered to go into the front room? And I was like, “Oh, come on, let’s just go and sit out the front and drink some more.” Suddenly, by the time I started working there six months later, they’d had the biggest-selling debut and it was starting to go crazy. Alan was there that night, I bought him a Jack and coke when he came back in from the Oasis bus but that was the last time I saw him before he was off for a bit.’

*

Tim Abbott remembers being at a techno night at the time, run by his brother Chris in East London, and being asked by a bouncer whether Stein, whom the bouncer had assumed was a member of the drug squad impersonating an American tourist, was to be granted admission.

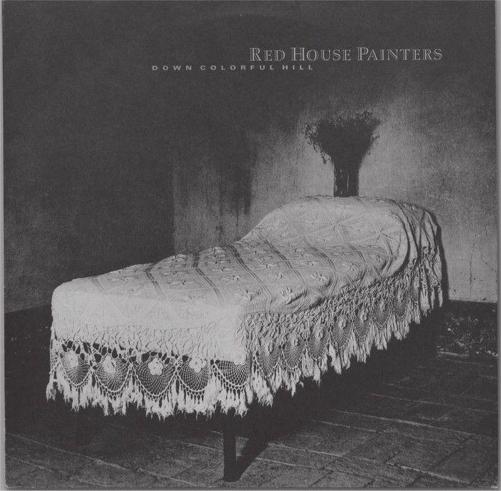

Red House Painters,

Down Colorful Hill

, CAD 2014 (

Vaughan Oliver/4AD

)

A

lan McGee wasn’t the only label head absent from the office. By 1993 Ivo Watts-Russell was dividing his time between America and Britain, a result of his continuing and increasing frustration with the manner in which 4AD was now expected to be run. Having succeeded on its own terms with the Pixies, the label was under pressure to deliver similar results for the rest of its artists. ‘I am disappointed that I didn’t fight or resist it when the managers would say, “Where’s the hit?”,’ he says. ‘I mean, why the fuck have they signed with us then?’

The international growth of the label required a further enlargement of the workforce and a move towards a structure beyond Watts-Russell’s preferred methods of releasing bands whose music he loved and letting the records do the work. Much to his chagrin, 4AD now had a dedicated meeting room, where Watts-Russell tried to spend as little time as possible. ‘There was more of a feeling of feeding the machine,’ he says, ‘and not feeling happy about the way that machine was being fed and the fact it had become a machine.’

Despite his lingering sense of discontent, Watts-Russell made several attempts to bypass the machine. When in the office, he still made a habit of going through the demo tapes from which he had, over the years, regularly found new signings. Sifting through the cassettes now also provided a distraction from the tension of office politics. A song title that had been handwritten on one of the demos, ‘I Had Sex with God’, caught his eye. The

track was credited to His Name Is Alive, an American band based on the four-track tapes of its songwriter Warren Defever. The music was primitively recorded but had a beguiling otherness. ‘I started getting more tapes from him,’ says Watts-Russell. ‘They were the same songs but he was deconstructing them, just leaving a skeleton. I liked it, but said, “Can I mix it?” I went in the studio with John Fryer and we mixed

Lavonia

, and I feel closer to that than to any other record we did, other than This Mortal Coil, for the obvious reasons.’ Watts-Russell once again found comfort in Blackwing, reworking a set of tapes, absorbed in the creation of another record of reflective and personal music. The resulting album,

Lavonia

, had an abstraction and fragility that spoke heavily of Watts-Russell’s state of mind; it also drew comparisons to This Mortal Coil. Although the songs featured the choral vocals of Karin Oliver they retained the rough edge of demos and had a harsh, fractured quality. One of the songs was entitled ‘How Ghosts Affect Relationships’– it might have been describing how Watts-Russell felt about 4AD. He had moved into a new home in London. In his increasingly solitary moments, he shared his new surroundings with

Lavonia

and little else.

‘I’d just moved into this flat in Clapham,’ he says, ‘the first place I ever lived in with tall ceilings. So I was just in there with a sofa that was too big to go anywhere else and suddenly I felt insecure about how could I fill this room with just me. I mixed the tapes and listened to them really quietly in this high-ceilinged room, so quietly that my alarm, which was a ticker, was louder than the music.’

For someone who as a child had taken solace in the music coming from his small bedroom transistor late at night,

Watts-Russell

had come full circle. Quietly absorbed in the

Lavonia

masters he cut himself further adrift from the comings and goings in Alma Road. As well as struggling to maintain his

emphasis on creativity and A&R, he was having difficulties in some of his relationships. He had split with his partner Deborah Edgely and was, for the first time, starting to have increasingly fractious conversations with some of his artists.

‘I probably sequenced about 80 per cent of the records we put out,’ he says. ‘On the last day in the studio, on the last Pixies record, I’d done a running order for it. We were going to go out for supper, and Charles went, “No, I’m going to do a running order; it’s going to be alphabetical.” I ended up falling out badly with Charles and Robin Guthrie, the only two people I’ve ever fallen out with long term.’

Lavonia

had shown that Watts-Russell’s affection for music hadn’t diminished but the passion with which he was able to apply himself was wavering. As a way of circumventing the expectations and pressures of launching a new band on 4AD, he started a sub-label, Guernica, with the sole motive of releasing records he liked. In the States he had discovered a new generation of bands, including Unrest and That Dog, who had self-released material which he felt could benefit from wider distribution; Watts-Russell also heard in these bands the sound of younger artists making music on their terms, away from the strictures of the industry; a sound he had almost forgotten. ‘I was driving up to Big Sur,’ says Watts-Russell, ‘listening to Unrest and feeling really connected to something. Guernica was significant in that I just thought, fuck it. I just want to put a record out that I think is good. The budget would be 5k and that’s it; we won’t release singles, and we’ll never release albums by the same artist.’

The idea of Guernica was straightforward, but within the 4AD system it lacked coherence. The fact that Watts-Russell had all but moved to the States also meant there was no one in the London office to drive the project forward. He had conceived Guernica as a way of rekindling his love of releasing records

without the pressures of career building and long-term planning, but had instead created another pressure in an ongoing series of communication problems at 4AD.

‘Guernica didn’t fucking work because Ivo, the bloke who ran the company, had fucked off to the USA’, says Watts-Russell, ‘and dumped this stuff back on the label and wasn’t there to guide it through. It didn’t seem to work for the artists or the people back there.’ Simon Harper was acting as a de facto label manager in Watts-Russell’s absence and was one of the few members of staff included in his confidence. As Watts-Russell considered emigrating to live full-time to America, he and Harper started to make some contingencies for how the label would be run while he was away. The reality was that 4AD, without the singular vision and authorial voice of its founder, would be a difficult company to steer.

‘I was aware of the fact that he didn’t want to live in England for a myriad of reasons,’ says Harper. ‘He wasn’t having a great time with the industry and so it came as no surprise to me that he was moving to the States. When he moved there, things obviously started to become slightly more complicated primarily on the A&R front. We had a very capable A&R guy in London called Lewis Jameson, but it was obviously going to be an issue as to how practical it would all be in terms of Ivo’s involvement.’

Away from his unease in the industry and his despondency over 4AD, Watts-Russell was beginning to realise that his personal problems were also starting to become difficult to manage. In search of sunlight, he took himself away over the Christmas and New Year break of 1992–3 to Thailand, where, rather than escaping his problems, he was confronted with their magnitude. ‘I’d gone to Thailand on my own,’ he says. ‘In Thailand, like lots of places, you can buy prescription drugs at the chemist. I came back with enough drugs to shuffle off this mortal coil. My

depression, it was becoming apparent, was something I really had to deal with.’

Robin Hurley had got to know Watts-Russell through Rough Trade America where Hurley had handled the Pixies and a number of 4AD acts. As Rough Trade began disintegrating, Watts-Russell suggested to Hurley that he would be welcome to join 4AD. Hurley moved the fledgling 4AD office from New York out to the West Coast where, in an example of how seriously the industry regarded 4AD’s chances of increased success, Warner Brothers were in the process of offering the label, rather than just a selection of its acts, a long-term deal.

‘Robin could tell I was down,’ says Watts-Russell. ‘I’d just got back from Thailand, and he said, “Why don’t you come out here for a month?”, as we’d opened the office. I thought, can I do that? I felt the old feeling when I’d come to America for the first time, years ago, that things are possible. I felt I could do this. I rented an apartment in LA and I tried to live in both places and go back and forth. It took me a while to settle in LA and work out what the fuck I was doing and then when I was back in the UK I felt cheated that I was back because I didn’t want to be there. I was exhausted and it contributed to me going off the rails.’

To Vaughan Oliver, Watts-Russell’s emigration had come as a shock. While their relationship had always fluctuated with their moods, Oliver had been a constant presence since 4AD’s infancy and the designer was horrified that he would now be answering to an ad hoc selection of 4AD label managers rather than directly to Watts-Russell. ‘I didn’t see that coming,’ he says. ‘He said, “That’s where I’m going, that’s what I’m doing. I’m going back to LA.” “Right, oh, I’m sorry about that …” It’s not as if we even had dinner together and discussed it. It just happened and I had to accept it – these divvies coming in and running the company, with him in the background.’

Watts-Russell’s relocation had a further implication for Oliver. For a long time the designer had felt that his input into the label had never been fully recognised. In an awkward moment some years earlier, he had brought up the subject of becoming a shareholder or partner in 4AD, a suggestion that surprised Watts-Russell. ‘In 1984 I suggested that I should be a partner,’ recalls Oliver. ‘Ivo said something to the effect of “fuck off”, which nearly had me in tears. He said, “Well, what money are you going to put in?” It was just an idea. It lasted about three minutes and I scuttled back into my box.’

Other members of staff were under the impression that Oliver still bore a grudge that, combined with his temperament, made his relationship with Watts-Russell increasingly choleric. Oliver, whose work will be for ever associated with 4AD, still maintains that his contributions are underappreciated. ‘Looking in, folks would have thought I’m a partner,’ he says. ‘When Ivo sold the company, I should’ve had some fucking money out of it. You put twenty years of your life into something …’

Throughout his period at the label Oliver was also engaged in freelance commissions, but it is the unique use of typography, colour and photography he applied to 4AD’s record sleeves for which he is most recognised. Whatever the difficulties of the relationship between them as label owner and graphic designer, the partnership between Oliver and Watts-Russell was one of the most creatively successful to have survived the ups and downs of the music business. Oliver’s designs are instantly identifiable and synonymous with 4AD; his bold strokes and willingness to experiment, a suitably individual and vivid representation of the label’s music.

‘A few years ago someone said to me, “You’ve created a brand, v23’s a brand, 4AD’s a brand,”’ says Oliver, ‘that’s not what you aspire to, you’re just trying to make something that’s true … it’s

about truth isn’t it, and that’s all we were trying to do.’

Through the turbulence of emigrating and the problems of how he would be replaced, Watts-Russell managed to sustain his interest in music. While the label may have employed an A&R man, Watts-Russell continued to listen to the demos and tapes that came his way and maintained a close working relationship with the new generation of acts he had signed, almost all of whom were solo performers. One of his later signings especially saw him work with an artist in the manner in which he had enjoyed his most successful partnerships. ‘Ultra Vivid Scene, His Name, Heidi Berry, Lisa Germano, I love those records,’ says Watts-Russell, ‘and Red House Painters in particular.’

Red House Painters were a Bay Area band formed by Mark Kozelek, whose lugubrious singing and atmospheric chord changes gave his songwriting a hushed intensity. A fellow San Franciscan, Mark Eitzel, had passed a whole C90 cassette’s worth of Kozelek’s songs to the journalist Martin Aston, one of 4AD’s few long-term supports in the media, who sent the tape to Watts-Russell.

‘The first time I listened to it all the way through, I rang Mark Kozelek,’ says Watts-Russell. ‘He was in the bath and heard my voice on the answering machine. That was a fantastic collaboration between us. There was that hour and a half, quickly followed by tons of tapes, long songs. So I said to him, similar to

Come On Pilgrim

, “Let’s pick six songs put them out as it is, and let’s do another record and re-record some of it.”’

Watts-Russell and Kozelek picked the six tracks that would comprise

Down Colorful Hill

and Watts-Russell decamped with John Fryer to the studio where, for one last recording session as the head of 4AD, he shadowed the Red House Painters songs in a light haze of reverb. The Red House Painters’ material that was released had an echo of 4AD before the label’s multiplatinum

success and its unhappy evolution into a machine.

Red House Painters’ music also corresponded closely to Watts-Russell’s frame of mind.

Down Colorful Hill

had a

vulnerability

and directness to which the increasingly fragile

Watts-Russell

could relate. Working closely with Kosolek had offered him an opportunity to do what he most enjoyed: producing and compiling a record with an artist in a mutually rewarding process. ‘It was very bleak,’ says Watts-Russell. ‘This very melancholy sound.’ Although a welcome distraction from his problems, Red House Painters offered only temporary respite for him. ‘I suppose by the third or fourth record we put out’, he says, ‘I started to lose the thread.’

In America the Warners 4AD deal that Hurley had supervised had been slow to yield results. Unrest’s

Perfect Teeth

had been a priority release and been given a significant push, to little effect. All was not lost however, by the time Dead Can Dance released

Into the Labyrinth

, Warners finally had a release that could justify the deal.

‘Warners were putting out as many records in a month as we were doing in a year,’ says Hurley. ‘

Into the Labyrinth

came out into the chart at no. 75 or something and went on to do half a million sales. So we thought, “Ah, light at the end of the tunnel. We’ve turned a corner,” and at the same time Belly did really well – they were part of the Warner group – Ivo had been very involved in the recording and it reflected well on us that the A&R was working.’