How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (8 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

Among the anecdotes, salacious gossip and hustler’s advice that poured out of Stein was a piece of wisdom that, in its

hard-headed

pragmatism at making the music industry work for you, Drummond found astonishing. One particular piece of advice horrified him: ‘Seymour says, “Bill, this is how you make money out of the music business: you do a deal with a record label. You say, ‘I’ll give you six albums, and you give me x thousand dollars.’ So, say he gets 100,000 dollars for six albums, you go out and you sign six bands, any old bands, it doesn’t matter who they are, you stick them in a studio, you record an album and you record the album for 5,000 dollars. The band will love you ’cause they get to record an album – that’s all they’ve ever wanted to do all their lives. You tell your band, ‘OK you’ve got to get it done in four or five days,’ and you get the album done. So you’ve got your six albums done for under 20,000 dollars, whatever. You’ve just made yourself 80,000 dollars. It doesn’t matter a fuck whether these records happen or not.”’

This cold-hearted reality was an eye-opener for Drummond, who couldn’t help but notice when, a few years later, Stein’s business model had failed him. ‘Seymour came a cropper doing it his way. This was in parallel with his total love of music: these two things were running in parallel but once he got Madonna it was fucked. It wasn’t really even in his interests with Talking Heads or for the Ramones or any of us, or any of them, to sell a lot of records, ’cause suddenly he’d be owing them royalties –

money he’d already spent on art deco stuff, and on his houses. So when Madonna starts really selling, he’s rumbled. He can’t do it any more, so that’s when he has to sell his whole thing to Warner or whatever it was – 51 or whatever per cent – I mean, he ended up selling the whole lot and that’s the reason.’

With Dickins in with the money side of the deal, Stein had his elliptical northern band tutored in Drummond’s air of mystique. Stein’s vision of an alternative Eighties would pay dividends throughout the decade as a succession of pale British boys from the provinces would find themselves flown across the world by Sire, walking out on to the arena stage, blinking into the Santa Monica sun.

As the decade was just starting, all Mick Houghton was witnessing in the Warner press department, however, was real horror at the thought of any of this kind of music succeeding. ‘The first year I was there, the groups like the Bunnymen, Talking Heads, Ramones were getting mountains and mountains of press, the guys in promotion and radio just thought it was unplayable. Warners at that stage didn’t see any kind of commercial potential in those records. I think they were also reeling, to a certain extent, from the reaction of punk against their stable of artists, the Foreigners and Fleetwood Macs. But obviously the whole thing about punk was that it didn’t change anything in terms of certain rock dinosaurs – Genesis, Yes, the Moody Blues of this world – who were possibly more successful after 1980 than they were before, and after Live Aid it just expanded those bands’ horizons to an even greater extent. I was always aware anything coming out of America had that kind of corporate clout behind it. If it was Foreigner, there’d be a big hoo-ha you know, getting them press, getting them radio, and there was inevitably some huge lavish reception. The only reason I remember the Foreigner one is that there was an album called

Cold As Ice

, and they threw

this massive reception at some Intercontinental hotel and they thought it was a really good idea to have the

Cold As Ice

logo, in ice, but it was delivered some time in the afternoon so by the time everyone got there, this thing just melted and dripped all over the floor.’

For Rob Dickins, the young English executive running the London offices of an American company, having hatched a scheme for him and Stein to develop home-grown talent, the future lay somewhere over the horizon with this new emerging guitar music.

‘The Bunnymen happened quite quickly in that sense,’ says Houghton. ‘The Bunnymen only made one single for Zoo, and I think Rob Dickins was astute enough – Rob wanted a label that was like Stiff, he wanted a label that had hit records.’

But Dickins would have to wait for his hit from the Bunnymen, for all the press inches Houghton racked up for the band, and for all Drummond’s

mise en scène

, the radio department at the record company, never mind the playlist controllers at daytime radio, remained hostile. ‘It took the Bunnymen three albums and countless singles before “The Cutter” went Top Twenty, says Houghton. ‘Before that they had the odd “single of the week” in the music press and being played on John Peel, I mean that was it.’

For Drummond, beyond his mythic approach to managing his charges, which meant his idea of planning a campaign was a day of bike rides culminating in a performance at Liverpool Cathedral, the record business remained a thing of blunt, bemusing nonsense. ‘The demograph,’ he says, ‘is a word I learnt in California. “What is the demographics of Echo & the Bunnymen?” “What are you talking about?” Demographics? The demograph is whoever buys the record, that’s the demograph.’

Drummond, who would draw rabbits’ ears over maps and

plan a tour accordingly, was on a different path. The Bunnymen’s performances of ‘A Crystal Day’ at Liverpool Cathedral, touring the leylines of the Orkneys and playing the Albert Hall, while securing their position as the ultimate cult band of the 1980s, were above all an article of faith in the grand gesture.

‘The Orkney Islands tour, the Crystal day, the romance of it all,’ says Houghton, ‘the romance of it all but also the gesture – what Bill has always been good at was the gesture.’ And if his love of the gesture was only half-realised in his managerial capacity for Echo & the Bunnymen, when he re-entered the music business as an artist several years later these gestures, traceable in part back to the ideas of

The Illuminatus!

at the Liverpool School of Language, Music, Dream and Pun, and partly, an outrageously self-confident response to the rave culture spilling out around him, would be magnified, contorted and escalated into one of the most astonishing acts of theatre in the history of independence. Not to mention one of its most lucrative.

*

Bill Grundy famously attempted to interview the Sex Pistols for Thames Television on 1 December 1976, but the broadcast deteriorated into an

intergenerational

swearing match.

†

The advertising campaign for

Ocean Rain

contained the strapline ‘The Greatest Record Ever Made’. ‘That was my idea’, says Drummond. ‘I mean, why fuck around? The marketing department never spoke to me again.’

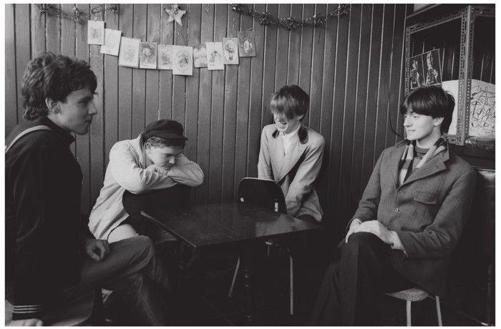

An early Orange Juice photo session featuring Alan Horne standing in for absent bassist David McClymont. From left to right, Steven Daly, Alan Horne, Edwyn Collins, James Kirk (

photograph by Tom Sheehan used by kind permission of the photographer

)

‘

A

t the time when we were forming Postcard,’ says Edwyn Collins, ‘the things that got adopted later by the

jingly-jangly

groups … I never really liked the interpretation of it, I just remember a lot of spitting going on.’ In Glasgow, punk had happened a little later than the rest of the UK, but its in-

your-face

brutish side had found an affinity with the city’s take-

no-prisoners

night-time etiquette. ‘Punk in Glasgow’, says Collins, ‘was a lot of groups called The Sick and The Vomit, The Drags, The Jokes. Glasgow was comfortable with that and always had that tough guy, no messing, obsession.’

Collins was still at school when the first wave of punk arrived in Glasgow. His fellow pupils at Bearsden Academy, a secondary school in one of the city’s less turbulent suburbs, included Steven Daly and James Kirk. ‘All the Postcard people came from a teenage thing of not being tremendously confident,’ says Collins. ‘We were never the kids at school that people wanted to hang out with. When we met each other, we were all coming from an outsider perspective, it informed the way we were with each other.’

Collins, who read

NME

on the school bus, first noticed Daly, a few seats further down, reading the

Melody Maker

. Any potential kudos Collins thought he might gain by reading the less prog weekly was negated by Daly’s horror at the fact Collins proudly wore a Buddy Holly badge.

Their mutual passion for devouring music, hinging on such

teenage minutiae as David Bowie’s hairstyles, Donna Summer’s appearances on

Top of the Pops

and forgotten Sixties B-sides, blossomed into Collins, Kirk and Daly dipping their collective toes into the punk ripples by starting a fanzine. Rather than covering The Sick or The Vomit, their fanzine was, tellingly, more interested in music from the past.

‘We did a fanzine in ’77 called

No Variety

,’ says Collins. ‘James wrote political pieces. When the Scotland football team were going to play in Chile, in the stadium where they’d had the executions in ’74 during the military coup, James wrote about why they shouldn’t do this, which ended with the line, “Will you wipe the blood from their football boots, Willy Ormond?” There were also retrospectives on the Troggs and I wrote a retrospective on the third Velvet Underground album.’

In the course of trying to sell fanzines in the local record shop, Daly had come across a fellow fanzine editor and self-publicist, Alan Horne. If Collins, Daly and Kirk had the textbook schoolboy desire to overcome their gawky shyness through their fanaticism with the pop world, Alan Horne seemed to be coming from somewhere slightly more perplexing:

‘Steven always wanted to be very hip,’ says Collins. ‘“Teenage Depression” came out the same week as “White Riot”, so he had two contrasting single reviews of them. He wrote, “Go fuck yourself, masters, fuck off with your pathetic old rock band. This is the only teen record that matters: ‘White Riot!’” Steven knew Alan Horne through the record shop Listen – they’d met through Alan’s fanzine,

Swankers

.’

Swankers

took the fanzine template into slightly uncharted waters. Instead of profiles of Ayrshire’s nascent punk scene or live reviews of what was happening around town,

Swankers

was a series of character assassinations by Horne. Those unlucky enough to be counted among his nearest and dearest found

themselves on the receiving end of his barbed and hostile surrealism. ‘He’d done

Swankers

solely to annoy his flatmate, Brian Superstar. They’d come from a seaside town south of Glasgow, a popular resort near Ayr. Alan called himself Eva Braun, and his friend the Slob, and he wrote about himself and Brian Superstar and this girlfriend character, Janice Fuck.’

Swankers

seemed to blend small-town xenophobia with the more decadent end of Sixties rock and its

amour fou

for the stylistic trappings of fascism. ‘There was a bigot’s quiz,’ says Collins, and the picture of Brian Jones with the SS uniform, with Brian Superstar’s head over it.’

Dismissing Horne’s politics as that of a bright but ignorant hick, Collins and Daly had detected an astonishing musical knowledge in Horne, coupled with an archness that frequently reduced them to hysterics. ‘We thought it was silly. Steven was very intolerant of anyone wearing swastikas, but he tolerated it in Alan, because Alan was also very camp. Alan insists that all the ideas he had then are the ones Morrissey had, and, because he’s adopted, he thinks Morrissey must have been his lost twin. Rita Tushingham, that whole frame of reference.’

With a piercing liquid gaze staring from behind glasses with either translucent or wire frames, Horne had cultivated a look that suited his thin build, somewhere between Truman Capote’s Factory screen test and a spikier version of Alan Bennett circa

Beyond the Fringe

. Holding it all together was a remarkable ability to project a fiercely vituperative intelligence.

Starting a shaky punk band of their own, the Nu Sonics, Collins, Kirk and Daly, though pleased to be making a racket, realised punk, especially Glasgow meat-and-potatoes punk, was creatively a dead end. ‘By ’79 none of us wanted to be associated with punk’, says Collins, ‘because of bands like Sham 69 and UK Subs coming up. All the neds.’

The Clash’s White Riot tour, however, would provide Scotland with a glimpse of a more interesting, subtle and less dogmatic musical style. Supporting the Clash in Glasgow were The Slits, Subway Sect and Buzzcocks.

‘I hung about at the stage door like you do when you’re a teenager,’ says Collins, ‘asking if I could help with the equipment. The Slits and Subway Sect were an astonishing proposition. Subway Sect’s guitarist, Rob Symmons, had a Melody Maker guitar. The sound made a big impression, as did The Slits because they couldn’t play but made a really charming noise.’

The White Riot tour had also called at Edinburgh and been seen by Malcolm Ross, a teenager who, along with school friend Paul Haig, had begun messing around with the idea of starting a band. ‘We were all at school together,’ says Ross. ‘We’d started jamming in 1977. I don’t think any of us would have made records if it hadn’t been for punk. I’d seen the White Riot tour, and Subway Sect was the one that stood out for me, the whole thing, the way they dressed as well.’

Along with creating a thrillingly feedback-saturated pop noise, Subway Sect eschewed the torn T-shirts and leather of punk. Instead they wore a subdued assemblage of v-neck sweaters, desert boots and shirts, often dyed grey. The band had an unaffected onstage gait that completed the look: a cross between a ’68

enragé

and a postman from a GPO film unit documentary winding down his shift at the sorting office. The blurring intensity of the sound and the second-hand tank tops and guitars would leave a huge impression on anyone who saw Subway Sect during their first year of touring. Ross could, however, detect one influence within Subway Sect’s monochromatic, brittle sound. ‘They were very much inspired by Television and so were we. Of all the groups that put out records in ’77, Television was the one that really connected. Paul Haig and I decided to try and play

guitar together because we both bought

Marquee Moon

and before them it was the Velvet Underground. Alan Horne used to talk about how Postcard was completely inspired by the VU.’

Collins, Kirk and Daly drew a line in the sand and started again; the new band would ignore what was happening around them and invent a new world of their own. ‘We had a whole load of new ideas,’ says Collins, ‘and we thought that the name Orange Juice would stand out like the proverbial sore thumb amidst all the punk names. I didn’t think of any of the connotations the name would have with freshness, or anything like that. Steven liked it because he thought there was a psychedelic thing going to happen, and he thought, wash away the acid trip with orange juice. I wasn’t thinking of that. Alan liked it. We were briefly a three-piece, and I asked David McClymont to join as a bass player and Alan thought he was perfect. He thought he was like a little girl.’

As Collins, Kirk, McClymont and Daly made plans for the newly configured Orange Juice, Horne recognised the need to stay one step ahead and decided that he would not only manage the band, but start a label to release their wares: Postcard Records.

For a record company that in its lifetime released only a handful of 7-inch singles and a stillborn album, Postcard’s legacy and influence is almost unquantifiable. In his third-floor tenement flat at 185 West Princes Street in the West End, while he and Collins filtered through their tastes to fix a Postcard aesthetic, Horne was equally interested in maintaining as high a level of cattiness as possible.

Orange Juice understood the need to elicit a reaction from the prevailing orthodoxy of Glaswegian punk, so took to the stage looking gauche and fey. Collins’s boyish baritone carried the courage of its convictions, revelling in its triumph of hope over experience in hitting the high notes. The rhythm section of McClymont and Daly, while hoping to sound like Chic, sounded

exactly what it was, two boys in their early twenties thrilled at the idea of trying to sound like Chic.

As well as sounding charmingly insouciant and giddy from its self-consciousness, Orange Juice had developed a look that put its unorthodox individuality stage front. Collins would take to the stage in cavalry boots and a Davy Crockett hat, his fringe almost long enough to collide with his toothy grin. The rest of the band, in sports jackets and checked shirts, looked like country and western intellectuals who were enjoying the idea of being in a group while also coming to terms with their second-hand equipment. While it was provocative to the punk neds down at the front of the stage shouting abuse, it had an infallible warmth and charm. ‘I bought the boots and the Crockett hat in a shop in Edinburgh,’ says Collins. ‘We were deliberately camping it up and feying it up in order to provoke, and of course the audience duly responded with “Poofs poofs poofs”.’

After a particularly challenging gig at Glasgow Technical College, Collins, Horne and the rest of the band were wheeling a borrowed Vox Continental organ up Byres Road when they were set upon by youngsters out on the street looking for some late-night thrills – and who were deeply unimpressed by Orange Juice’s attitude and appearance. ‘Alan Horne ran away,’ says Collins. ‘I got beaten up. James Kirk said to me, “That, Edwyn, is the definition of grace under pressure,” then the police arrived and found it all very confusing and looked at us very suspiciously. And of course, Alan loved all that.’

Camping it up in Glasgow, despite Horne’s delight at the provocation, was proving to be not without its perils. ‘I mean, it was quite hard to be gay in Glasgow in 1980,’ says Collins. ‘Almost impossible. I remember, there was one gay bar but you had to keep your head down.’

All this campness was no less in your face than the Glaswegian

hard-man archetype – it was practically its feminisation – so much so that it struck a nerve. Along with Collins and Horne’s switchblade wit and uncompromising way with a put-down there was, behind the charm, something confrontational about Postcard and Orange Juice’s gaucheness.

As Orange Juice took a step into the unknown and began recording their debut single, Horne and Collins’s ideas for Postcard began taking shape. On Postcard, singles would feature photography on the sleeve of their first pressing, subsequent

repressings

would be housed in a uniform pastel beige in-house sleeve which would be stickered with Caledonian imagery: clansmen in kilts, tins of shortbread and lochs at sunset. The Postcard logo would be a grinning cat and, completing this détournement of nationalist boosterism would be the label’s mission statement: ‘Postcard Records, The Sound of Young Scotland.’ These tongue-in-cheek signifiers were as much an expression of Horne’s supreme yet deeply fragile self-confidence and sarcasm as of Postcard’s irreverent sense of playfulness.

Instead of the monochromes or scratchy xerox and biro aesthetics of the singles filling up the back room of Rough Trade, here was sly, stylish fun, openly willing to embrace such exiled ideas as wit and naivety. This sentiment was particularly echoed in Orange Juice’s music: a chiming mix of the Sixties and the contemporary sleekness of chart disco, cherry-picked to bounce off attempts at conveying late teenage soulfulness. ‘I liked the Byrds, the Velvets, the Beatles, Creedence Clearwater Revival. We were big on the Lovin’ Spoonful and all Stax stuff,’ says Collins. ‘We already knew about all of that by the time we started Orange Juice.’ Alongside such sleekly escapist chart staples as the O’Jays’ ‘Love Unlimited’, for the first time since punk, Postcard, via Orange Juice’s willingness to open up to their influences, was happy to allow in the past.

All the labels that had started around the energies of punk had been preoccupied either with the future or the insistent now of the present. Mute, Factory, and Industrial had developed an aesthetic based on the austerity of clean lines while Rough Trade, taking its cue from

Spiral Scratch

’s photostatted presentation of the facts, had the aura and cut-and-paste energies of a fanzine in vinyl form. Fast Product’s imagery codified the DIY impulse, setting it in a playfully theoretical context – pictures of gold discs on the front of the Mekons’ ‘Where Were You?’ – that revelled in its high design values. Zoo, though awash with a romanticism that looked in all directions, shared the greyish raincoat hue of post-punk, and in Echo & the Bunnymen had a band with that most modern of instruments, a drum machine. Postcard, with its sporrans and cat’s whiskers, was asking the listener, before they even put the record on, to forget all that. This was a Warholian pop art commentary on commodification and culture, Glasgow West End style, on a budget and with a truckload of attitude.

In his high-ceilinged room in Princes Street, taking up space next to the stereo, tucked behind a tailor’s mannequin upon which he kept his sunglasses, Horne had a battered suitcase full of 7-inch vinyl, a treasure chest full of the mythic properties of the 45-rpm single whose contents were laid out in rows. ‘He had original presses of things like Big Star’s “September Gurls” on Ardent,’ says Collins, ‘Sue, Motown, Stax, red label Elektra, all lined up.’