How the French Invented Love (28 page)

Read How the French Invented Love Online

Authors: Marilyn Yalom

C

harles takes Emma to the opera in Rouen in the belief that a diversion will do her good. Settled into her box, she gives herself over to

Lucie de Lammermoor

sung by the famous tenor Lagardy. Her recollection of the novel by Walter Scott, on which the opera is based, makes it easier for her to follow the libretto, and soon she is bathed once more in the vapors of romantic love. If only she had found a man like Lagardy!

With him she would have traveled through all the kingdoms of Europe, from capital to capital, sharing his troubles and his triumphs . . . she wanted to run into his arms, take refuge in his strength, cry out to him: “Lift me up, take me away, let us go away! All my passion and all my dreams are yours, yours alone.”

Do women think like this anymore in the twenty-first century? Did they ever think like this? We are tempted to attribute Emma’s absurd longings to Flaubert’s masculinist view of what women want, but is that fair? Haven’t we seen from Julie de Lespinasse that some women did indeed derive their entire self-worth from possessing a man’s love, and some women probably still do.

What’s more, Flaubert could draw upon aspects of his mistress, Louise Colet, a dyed-in-the-wool romantic endowed with the tempestuous fervor of her species. Senior to Flaubert by eleven years, she was clearly the one who loved more in their relationship. Some details in

Madame Bovary

can be traced directly to Colet, such as the cigar case with the motto

Amor nel cor

that she gave Flaubert at the beginning of their liaison and which Emma offers Rodolphe in the novel.

Like her contemporary George Sand, Colet had many lovers, including some of the choice men of her era—the philosopher Victor Cousin, the poet Alfred de Vigny, and even Sand’s castoff, Alfred de Musset. And like Sand, she was a prolific writer who worked tirelessly to provide for herself and her daughter, with only a nominal husband and a stingy ex-lover (Victor Cousin) to help with her expenses. Flaubert, reclusively writing away at Croisset, loved Colet in his fashion—that is, he saw her rarely, made love avidly, wrote her regularly, criticized her work extensively, described his own literary process, and ended his relationship with Colet twice over an eight-year period, the second time for good. His remarkable letters to her contain treasured information about Flaubert as author and lover, and a vivid picture of Colet through his eyes.

Louise Colet was not the original source for Emma Bovary. That distinction belonged to a woman named Delphine Delamare, the wife of a country doctor from the Norman town of Ry and the mother of one child, a daughter. She, too, had acquired debts resulting from adulterous affairs and had committed suicide before the age of thirty. Flaubert knew about her only from the local newspapers. He took from Delamare, as he did from Colet and several other women, the raw materials he needed to create his hapless heroine.

I

t was at the opera that Emma Bovary was reunited with Léon Dupuis. Working for a notary practice in Rouen, he had gained considerable experience since his mute love for Emma several years earlier and was now in a position to make her his mistress. The scene in which their desires are consummated is one of the stylistic glories of all literature. First, they spend two hours touring the cathedral of Rouen under the guidance of an officious verger. Then, when Léon can stand it no longer, he sends for a cab and sequesters Emma for the longest city ride in Rouen’s history. The entire seduction scene is seen from outside the cab with its curtains drawn.

It went down the rue Grand-Pont, crossed the place des Arts, the quai Napoléon, and the Pont Neuf, and stopped short in front of the statue of Pierre Corneille.

“ ‘Keep going!’ ” said a voice issuing from the interior.

The carriage set off again and, gathering speed on the downward slope from the Carrefour La Fayette, came up to the railway station at a fast gallop.

“No! Straight on!” cried the same voice.

Three pages and five hours later, Emma emerged from the carriage, with her veil lowered over her face. This second affair, with a man less wealthy and less worldly than Rodolphe, may have been something of a comedown for Emma, but at least Léon was sincere in his love for her. They managed to meet every Thursday in Rouen under the pretense that she was taking music lessons.

Emma became bolder. In her hotel room with Léon, “She laughed, wept, sang, danced, sent for sorbets, insisted on smoking cigarettes, seemed to him extravagant, but adorable, splendid.” Now it was the woman taking the lead, rather than the man. “He did not know what reaction was driving her to plunge deeper and deeper, with her whole being, into the pursuit of pleasure. She was becoming irritable, greedy, and voluptuous.” Over time, Emma and Léon became disenchanted with one another. She saw him as “weak, ordinary, softer than a woman.” He became frightened at her excesses and tried to rebel against her dominance. She realized that “she was not happy and never had been.”

In addition to the disintegration of her love affair, the overnight trips to Rouen added to Emma’s indebtedness to Lheureux. The net of doom began its inexorable descent. However foolish she had been, however much we try to distance ourselves from Emma, it is impossible not to get caught up in her final tragedy. Flaubert himself suffered agonies when he described her suicide by arsenic.

With

Madame Bovary

, French love had traveled a long way from chivalric romance. Instead of the idealized passion shared by a knight and his lady, Flaubert offers a debasing bourgeois melodrama. Instead of the noble renunciation suffered by the Princess de Clèves, we are asked to witness the degradation of a lustful provincial. Instead of the airborne romanticism of Sand and Musset, we feel the sharp edge of Flaubert’s cutting knife. Who would ever believe in romantic love again?

The 1870 military victory of Prussia over France did not help the French recover their sense of identity as lovers. Indeed, until the last decade of the century, pessimistic portrayals of love dominated French thought. Flaubert’s disciple Guy de Maupassant offered glimpses into bizarre behavior hidden under a veneer of normalcy. In his short stories, which were to acquire a worldwide readership, love is never more than a sensual hunger seeking satisfaction. Men and women of various social strata—gentlemen and ladies, peasants, shopkeepers, government workers—war against each other with an elegance of style that belies their underlying primitive needs. Love affairs prove disastrous, and marriage offers no relief, since husbands turn out to be either naïve cuckolds or brutal tyrants.

Even worse, Émile Zola’s novels between the 1860s and 1880s presented characters from the lowest levels of society—miners, factory workers, prostitutes, criminals—resembling animals in their mating habits. What Zola called “naturalism” was a pseudoscientific approach to society, part Darwinian, part Marxist, which saw hereditary degeneration everywhere. Love was subsumed into a kind of fertility cult—after all, the French (like the Germans) were obsessed with their declining birthrate. The best one could do was reproduce as frequently as possible. And yet, romantic love, like bulbs buried underground in the winter, was only waiting for the proper atmosphere to flower again.

Love in the Gay Nineties

Cyrano de Bergerac

I

LOVE YOU,

I

’M CRAZY,

I

CAN’T GO ON ANY LONGER,

YOUR NAME RINGS IN MY HEART LIKE A BELL.

Edmond Rostand,

Cyrano de Bergerac,

1897

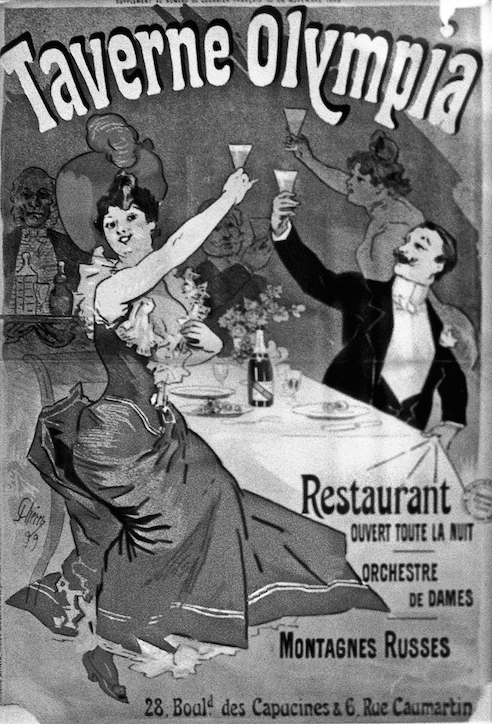

Taverne Olympia poster,

La Revue blanche

, 1899. Copyright Kathleen Cohen.

T

he gay nineties is the term we English speakers use for what the French call

la belle époque

. In both English and French, these terms evoke images of the Eiffel Tower, the bicycle craze, the posters of Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir’s paintings and Rodin’s statues, music halls, cabarets, operas and operettas, boulevard plays, art nouveau, the New Woman, courtesans, actresses, high fashion, high spending, and a host of other upbeat associations.

It is also possible to think of the gay nineties as a time when romantic love made a comeback. After Flaubert’s depressing realism and Zola’s heavy-handed naturalism, after the demoralizing defeat of the French by the Prussians in 1870, the Third Republic was ready to prove to the world that it was still the home of fashion, food, art, literature, and love.

To be sure, love could no longer be packaged in its earlier nineteenth-century forms. It had to be remodeled for a new age, one that had learned the lessons of its forebears and would neither wallow in the excesses of romanticism nor explore the moldy corners of the soul unearthed by Flaubert. Among the newly enriched café crowd, love was as effervescent and ephemeral as champagne bubbles. A man might lose a fortune on a celebrated courtesan, but he didn’t die for love—unless he was killed in a duel. Even though they were officially prohibited, duels proliferated around affairs of honor, which often meant around a woman. But even these could be lighthearted. Frequently, as soon as blood was shed from even a minor wound, the two men walked off the field arm in arm.

Love took on the theatrical aspect that was characteristic of everything else during the gay nineties. It was staged in ritualized settings, such as drawing rooms, hotel rooms, and the private dining rooms of fashionable restaurants. Those dining rooms were frequented by well-heeled men who wanted to entertain their ladies in private—that is, with the help of a knowledgeable maître d’hôtel and accommodating waiters. You can get an idea of what these private spaces were like from visiting the restaurant Lapérouse on the quai des Grands Augustins, opened in 1766 and still a perennial favorite among the affluent.

Men paraded with their mistresses or wives in horse-drawn carriages up and down the tree-lined Champs-Élysées or in the Bois de Boulogne. The women’s elaborate dresses, their plumed hats and boas, were designed to showcase hourglass figures propped up by serious whalebone corsets. The men in frock coats, monocles, and high silk hats proudly displayed their trophy women to the multitudes. As Pierre Darblay baldly stated in his 1889

Physiologie de l’amour

: “A man gets respect depending on the mistress he has.”

1

Lovers were no longer interested in communing with nature, unless it was at one of the chic coastal resorts like Trouville, Dieppe, or Deauville, where the attractions of the beach included the sight of women and men in full-body bathing suits. Marcel Proust, soon to become the greatest French novelist of the twentieth century, wrote nostalgically of his childhood trips with his mother to the Grand Hôtel at Cabourg (fictionalized under the name of Balbec) and rhapsodized about “the young girls in flower” who sprung up each year on the beach. Even when my husband and I stayed at the Grand Hôtel in the 1980s, it had the formal aura of bygone days, and the beach featured women displaying their charms. My husband, who had never seen a “topless” beach before, expressed keen appreciation for the female descendants of Proust’s delectable young women.

Fontainebleau, too, was a choice retreat for the moneyed class. Close enough to Paris for an overnight excursion, it was an ideal site for lovers who—like George Sand and Alfred de Musset in the 1830s—wanted to avoid publicity. Certain hotels became known for their discretion. To this day, high-placed government officials choose Fontainebleau for their trysts.

Still, no place rivaled Paris as the city of love. It had become, once again, a vast stage for all the enterprises that give piquancy to urban life—most notably, commerce, the arts, politics, and romance. The center of the city on both sides of the Seine possessed innumerable restaurants, cafés, hotels, shops, theaters, churches, public buildings, and parks where men and women of every social class could meet and fall in love. A letter in the mail, delivered the same day it was posted, could set up a rendezvous at the magnificent new Garnier Opera House. A few words across the counter with a pretty shop girl might result in a meeting later that night at a Montmartre cabaret. A working-class couple who had already set aside sufficient funds might go hand in hand to look over the restaurant where their wedding supper was to take place. Catholic fiancés on the verge of marriage met with their parish priests for the obligatory lessons on how to live in harmony with religious precepts. (How well I remember visiting the oldest church in Tours with a Catholic boyfriend, Pat McGrady, when we were both members of the Sweet Briar Junior Year in France, and a friendly priest took us for two sweethearts seeking premarital counsel!) Despite the extramarital freedom that many men and women enjoyed, most people did indeed marry. Bourgeois couples, tender and kitschy, looked forward to lifetime unions with the hope of domestic bliss. For, as Roger Shattuck succinctly remarked in his remarkable book

The Banquet Years

: “Love cannot last, but marriage must.”

2