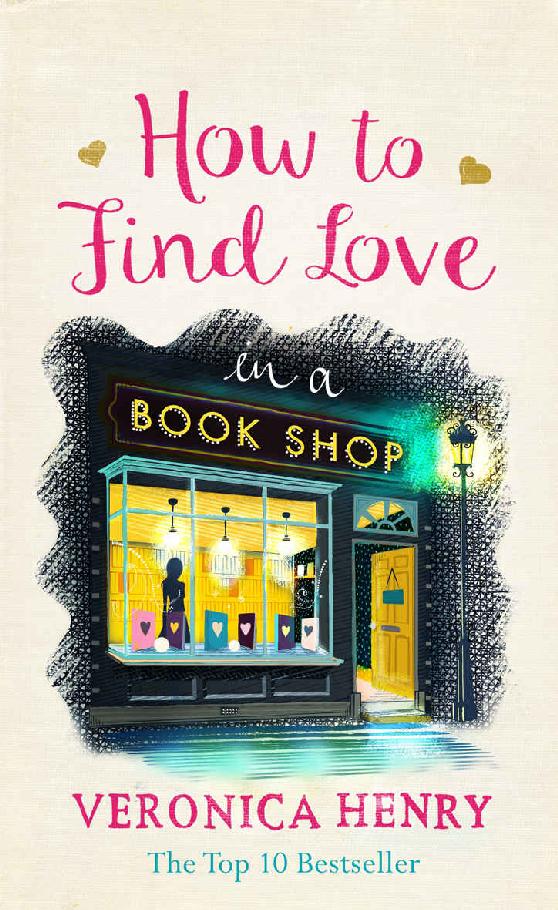

How to Find Love in a Book Shop

Read How to Find Love in a Book Shop Online

Authors: Veronica Henry

This book is dedicated to my beloved father,

William Miles Henry

1935–2016

Veronica Henry

Contents

‘Reading is everything’

NORA EPHRON

February 1983

H

e would never have believed it if you’d told him a year ago. That he’d be standing in an empty shop with a baby in a pram, seriously considering putting in an offer.

The pram had been a stroke of luck. He’d seen an advert for a garden sale in a posh part of North Oxford, and the bargain hunter in him couldn’t stay away. The couple had two very young children but were moving to Paris. The pram was pristine, of the kind the queen might have pushed – or rather, her nanny. The woman had only wanted five pounds for it. Julius was sure it was worth far more, and she was only being kind. But if recent events had taught him one thing it was to accept kindness. With alacrity, before people changed their minds. So he bought it, and scrubbed it out carefully with Milton even though it had seemed very clean already, and bought a fresh mattress and blankets and there he had it: the perfect nest for his precious cargo, until she could walk.

When did babies start to walk? There was no point in asking Debra – his vague, away-with-the-fairies mother, ensconced in her patchouli-soaked basement flat in Westbourne Grove, whose memory of his own childhood was blurry. According to Debra, Julius was reading by the age of two, a legend he didn’t quite believe. Although maybe it was true, because he couldn’t remember a time he couldn’t read. It was like breathing to him. Nevertheless, he couldn’t and didn’t rely on his mother for child-rearing advice. He often thought it was a miracle he had made it through childhood unscathed. She used to leave him alone, in his cot, while she went to the wine bar on the corner in the evenings. ‘What could go wrong?’ she asked him. ‘I only left you for an hour.’ Perhaps that explained his protectiveness towards his own daughter. He found it hard to turn his back on her for even a moment.

He looked around the bare walls again. The smell of damp was inescapable, and damp would be a disaster. The staircase rising to the mezzanine was rotten; so rotten he wasn’t allowed up it. The two bay windows either side of the front door flooded the shop with a pearlescent light, highlighting the golden oak of the floorboards and the ornate plasterwork on the ceiling. The dust made it feel other-worldly: a ghost shop, waiting, waiting for something to happen, a transformation, a renovation, a renaissance.

‘It was a pharmacy, originally,’ said the agent. ‘And then an antique shop. Well, I say antique – you’ve never seen so much rubbish in your life.’

He should get some professional advice, really. A structural survey, a quote from someone for a damp course – yet Julius felt light-headed and his heart was pounding. It was right. He knew it was. The two floors above were ideal for him and the baby to live in. Over the shop.

The book shop.

His search had begun three weeks earlier, when he had decided that he needed to take positive action if he and his daughter were going to have any semblance of normal life together. He had looked at his experience, his potential, his assets, and the practicalities of being a single father, and decided there was really only one option open to him.

He’d gone to the library, put a copy of the Yellow Pages on the table, and next to it a detailed map of the county. He drew a circle around Oxford with a fifteen-mile radius, wondering what it would be like to live in Christmas Common, or Ducklington, or Goosey. Then he worked through all the book shops listed and put a cross through the towns they were in.

He looked at the remaining towns, the ones without a book shop at all. There were half a dozen. He made a list, and then over the next few days visited each one, travelling by a complicated rota of buses. The first three towns had been soulless and dreary, and he had been so discouraged he’d almost given up on his idea, but something about the name Peasebrook pleased him, so he decided to have one last look before relinquishing his fantasy.

Peasebrook was in the middle of the Cotswolds, on the outer perimeter of the circle he had drawn: as far out as he wanted to go. He got off the bus and looked up the high street. It was wide and tree-lined, its pavements flanked with higgledy-piggledy golden buildings. There were antique shops, a traditional butcher with rabbit and pheasant hanging outside and fat sausages in the window, a sprawling coaching inn and a couple of nice cafés and a cheese shop. The Women’s Institute were having a sale outside the town hall: there were trestle tables bearing big cakes oozing jam and trugs of mud-covered vegetables and pots of herbaceous flowers drooping dark purple and yellow blooms.

Peasebrook was buzzing, in a quiet way but with purpose, like bees on a summer afternoon. People stopped in the street and talked to each other. The cafés looked pleasingly full. The tills seemed to jangle: people were shopping with gusto and enthusiasm. There was a very smart restaurant with a bay tree outside the door and an impressive menu in a glass case boasting nouvelle cuisine. There was even a tiny theatre showing

The Importance of Being Earnest

. Somehow that boded well. Julius loved Oscar Wilde. He’d done one of his dissertations on him: The Influence of Oscar Wilde on W.B. Yeats.

He took the play as an omen, but he carried on scouring the streets, in case his research hadn’t been thorough. He feared turning a corner and finding what he hoped wasn’t there. Now he was here, in Peasebrook, he wanted it to be his home –

their

home. It was a mystery, though, why there was no book shop in such an appealing place.

After all, a town without a book shop was a town without a heart.

A book shop could only make things better – for everyone in Peasebrook. Julius imagined each person he passed as a potential customer. He could picture them all, crowding in, asking his advice, him sliding their purchases into a bag, getting to know their likes and dislikes, putting a book aside for a particular customer; knowing it would be just up their street. Watching them browse, watching the joy of them discovering a new author; a new world.

‘Would the vendor take a cheeky offer?’ he asked the estate agent, who shrugged.

‘You can but ask.’

‘It needs a lot of work.’

‘That

has

been taken into consideration.’

Julius named his price. ‘It’s my best and only offer. I can’t afford any more.’

When Julius signed the contract four weeks later, he couldn’t help but be amazed. Here he was, alone in the world (well, there was his mother, but she was as much use as a chocolate teapot) but for a baby and a book shop. And as that very baby reached out her starfish hand, he gave her his finger to hold and thought: what an extraordinary position to be in. Fate was peculiar indeed.

What if he hadn’t looked up at that very moment, nearly two years ago now? What if he had kept his back to the door and carried on rearranging the travel section, leaving his colleague to serve the girl with the Rossetti hair …

And six months later, after weeks of dust and grime and sawing and sweeping and painting, and several eye-watering bills, and a few moments of sheer panic, and any number of deliveries, the sign outside the shop was rehung, painted in navy and gold, proclaiming ‘Nightingale Books’. There had been no room to write ‘purveyors of reading matter to the discerning’, but that was what he was. A bookseller.

A bookseller of the very best kind.

Thirty-two years later …

What do you do, while you’re waiting for someone to die?

Literally, sitting next to them in a plastic armchair that isn’t the right shape for

anyone’s

bottom, waiting for them to draw their last breath because there is no more hope.

Nothing seemed appropriate. There was a room down the corridor to watch telly in, but that seemed callous, and anyway, Emilia wasn’t really a television person.

She didn’t knit, or do tapestry. Or sudoku.

She didn’t want to listen to music, for fear of disturbing him. Even the best earphones leak a certain timpani. Irritating on a train, probably even more so on your deathbed. She didn’t want to surf the Internet on her phone. That seemed the ultimate in twenty-first-century rudeness.

And there wasn’t a single book on the planet that could hold her attention right now.

So she sat next to his bed and dozed. And every now and then she started awake with a bolt of fear, in case she might have missed the moment. Then she would hold his hand for a few minutes. It was dry and cool and lay motionless in her clasp. Eventually it grew heavy and made her feel sad, so she laid it back on the top of the sheet.

Then she would doze off again.

From time to time the nurses brought her hot chocolate, although that was a misnomer. It was not hot, but tepid, and Emilia was fairly certain that no cocoa beans had been harmed in the making of it. It was pale beige, faintly sweet water.

The night-time lights in the cottage hospital were dim, with a sickly yellowish tinge. The heating was on too high and the little room felt airless. She looked at the thin bedcover, with its pattern of orange and yellow flowers, and the outline of her father underneath, so still and small. She could see the few strands of hair curling over his scalp, leached of colour. His thick hair had been one of his distinguishing features. He would rake his fingers through it while he was considering a recommendation, or when he was standing in front of one of the display tables trying to decide what to put on it, or when he was on the phone to a customer. It was as much part of him as the pale blue cashmere scarf he insisted on wearing, wrapped twice round his neck, even though it bore evidence of moths. Emilia had dealt with them swiftly at the first sign. She suspected they had been brought in via the thick brown velvet coat she had bought at the charity shop last winter, and she felt guilty they’d set upon the one sartorial item her father seemed attached to.

He’d been complaining then, of discomfort. Well, not complaining, because he wasn’t one to moan. Emilia had expressed concern, and he had dismissed her concern with his trademark stoicism, and she had thought nothing more of it, just got on the plane to Hong Kong. Until the phone call, last week, calling her back.

‘I think you ought to come home,’ the nurse had said. ‘Your father will be furious with me for calling you. He doesn’t want to alarm you. But …’

The ‘but’ said it all. Emilia was on the first flight out. And when she arrived Julius pretended to be cross, but the way he held her hand, tighter than tight, told her everything she needed to know.

‘He’s in denial,’ said the nurse. ‘He’s a fighter all right. I’m so sorry. We’re doing everything we can to keep him comfortable.’

Emilia nodded, finally understanding. Comfortable. Not alive. Comfortable.

He didn’t seem to be in any pain or discomfort now. He had eaten some lime jelly the day before, eager for the quivering spoons of green. Emilia imagined it soothed his parched lips and dry tongue. She felt as if she was feeding a little bird as he stretched his neck to reach the spoon and opened his mouth. Afterwards he lay back, exhausted by the effort. It was all he had eaten for days. All he was living on was a complicated cocktail of painkillers and sedatives that were rotated to provide the best palliative care. Emilia had come to hate the word palliative. It was ominous, and at times she suspected ineffectual. From time to time her father had shown distress, whether from pain or the knowledge of what was to come she didn’t know, but she knew at those points the medication wasn’t doing its job. Adjustment, although swiftly administered, never worked quickly enough. Which in turn caused her distress. It was a never-ending cycle.

Yet not

never

-ending because it

would

end. The corner had been turned and there was no point in hoping for a recovery. Even the most optimistic believer in miracles would know that now. So there was nothing to do but pray for a swift and merciful release.

The nurse lifted the bedcover and looked at his feet, caressing them with gentle fingers. The look the nurse gave Emilia told her it wouldn’t be long now. His skin was pale grey, the pale grey of a marble statue.

The nurse dropped the sheet back down and rubbed Emilia’s shoulder. Then she left, for there was nothing she could say. It was a waiting game. They had done all they could. No pain, as far as anyone could surmise. A calm, quiet environment, for incipient death was treated with hushed reverence. But who was to say what the dying really wanted? Maybe he would prefer his beloved Elgar at full blast, or the shipping forecast on repeat? Or to hear the nurses gossiping and bantering, about who they’d been out with the night before and what they were cooking for tea? Maybe distraction from your imminent demise by utter trivia would be a welcome one?

Emilia sat and wondered how could she make him feel her love, as he slipped away. If she could take out her heart and give it to him, she would. This wonderful man who had given her life, and been her life, and was leaving her alone.

She’d whispered to him, memories and reminiscences. She told him stories. Recited his favourite poems.

Talked to him about the shop.

‘I’m going to look after it for you,’ she told him. ‘I’ll make sure it never closes its doors. Not in my lifetime. And I’m never going to sell out to Ian Mendip, no matter what he offers, because the shop is all that matters. All the diamonds in the world are nothing in comparison. Books are more precious than jewels.’

She truly believed this. What did a diamond bring you? A momentary flash of brilliance. A diamond scintillated for a second; a book could scintillate forever.

She doubted Ian Mendip had ever read a book in his life. It made her so angry, thinking about the stress he’d put her father under at a vulnerable time. Julius had tried to underplay it, but she could see he was upset, fearful for the shop and his staff and his customers. The staff had told her how unsettled he had been by it, and yet again she had cursed herself for being so far away. Now she was determined to reassure him, so he could slip away, safe in the knowledge that Nightingale Books was in good hands.

She shifted on the seat to find a more comfortable position. She ended up leaning forwards and resting her head in her arms at the foot of the bed. She was unbelievably tired.

It was two forty-nine in the morning when the nurse touched her on the shoulder. Her touch said everything that needed to be said. Emilia wasn’t sure if she had been asleep or awake. Even now she wasn’t sure if she was asleep or awake, for she felt as if her head was somewhere else, as if everything was a bit treacly and slow.

When all the formalities were over and the undertaker had been called, she walked out into the dawn, the air morgue-chilly, the light gloomy. It was as if all the colour had gone from the world, until she saw the traffic lights by the hospital exit change from red to amber to green. Sound too felt muffled, as if she still had water in her ears from swimming.

Would the world be a different place without Julius in it? She didn’t know yet. She breathed in the air he was no longer breathing, and thought about his broad shoulders, the ones she had sat on when she was tiny, drumming her heels on his chest to make him run faster, twisting her fingers in the thick hair that fell to his collar, the hair that had been salt and pepper since he was thirty. She held the plain silver watch with the alligator strap he had worn every day, but which she had taken off towards the end, as she didn’t want anything chafing his paper-thin skin, leaving it on the table next to his bed in case he needed to know the time, because it told a better time than the clock over the nurse’s station; a time that held far more promise. But the magic time on his watch hadn’t been able to stop the inevitable.

She got into her car. There was a packet of buttermints on the passenger seat she had meant to bring him. She unpeeled one and popped it in her mouth. It was the first thing she had eaten since breakfast the day before. She sucked on it until it scraped the roof of her mouth, and the discomfort took her mind off it all for a moment.

She’d eaten half the packet by the time she turned into Peasebrook high street and her teeth were furry with the sugar. The little town was wrapped in the pearl-grey of dawn. It looked bleak: its golden stone needed sunshine for it to glow. In the half-light it looked like a dreary wallflower, but in a couple of hours it would emerge like a dazzling debutante, charming everyone who set eyes upon it. It was quintessentially quaint and English, with its oak doorways and mullions and latticed windows, cobbled pavements and red letterboxes and the row of pollarded lime trees. There were no flat-roofed monstrosities, nothing to offend the eye, only charm.

Next to the stone bridge straddling the brook that gave the town its name was Nightingale Books, three storeys high and double fronted, with two bay windows and a dark blue door. Emilia stood outside, the early morning breeze the only sign of movement in the sleeping town, and looked up at the building that was the only home she had ever known. Wherever she was in the world, whatever she was doing, her room above the shop was still here; most of her stuff was still here. Thirty-two years of clutter and clobber.

She slipped in through the side entrance and stood for a moment on the tiled floor. In front of her was the door leading up to the flat. She remembered her father holding her hand when she was tiny, and walking her down those stairs. It had taken hours, but she had been determined, and he had been patient. When she was at school, she had run down the stairs, taking them two at a time, her school bag on her back, an apple in one hand, always late. Years later, she had sneaked up the stairs in bare feet when she came in from a party. Not that Julius was strict or likely to shout: it was just what you did when you were sixteen and had drunk a little too much cider and it was two o’clock in the morning.

To her left was the door that came out behind the shop counter. She pushed it open and stepped into the shop. The early morning light ventured in through the window, tentative. Emilia shivered a little as the air inside stirred. She felt a sense of expectation: the same feeling of stepping back in time or into another place she had whenever she entered Nightingale Books. She could be whenever and wherever she wanted. Only this time she couldn’t. She would give anything to go back, to when everything was all right.

She felt as if the books were asking for news. He’s gone, she wanted to tell them, but she didn’t, because she didn’t trust her voice. And because it was silly. Books told you things, everything you needed to know, but you didn’t talk back to them.

As she stood in the middle of the shop, she gradually felt a sense of comfort settle upon her, a calmness that soothed her soul. For Julius was still here, amidst the covers and the upright spines. He claimed to know every book in his shop. He may not have read each one from cover to cover, but he understood why they were there, what the author’s intent had been and who might, therefore, like to read them, from the simplest children’s board book to the weightiest, most indecipherable tome.

There was a rich red carpet, faded and worn now. Rows and rows of wooden shelves lined the walls, stretching right up to the ceiling – there was a ladder to reach the more unusual books on the very top shelves. Fiction was at the front of the shop, reference at the back, and tables in the middle displayed cookery and art and travel. Upstairs, on the mezzanine, there was a collection of first editions and second-hand rarities, behind locked glass cases. And Julius had reigned over it all from his place behind the wooden counter. Behind him were stacked the books that people had ordered, wrapped in brown paper and tied with string. There was an old-fashioned ornate till that tinged when it opened, which he’d found in a junk shop and, although he didn’t use it any more, he kept it, as decoration and sometimes he kept sugar mice in the drawer to hand out to small children who had been especially patient and good.

There would always be a half-full cup of coffee on the counter that he’d begun and never finished, because he would get into a conversation and forget about it and leave it to get cold. Because people dropped in to chat to Julius all the time. He was full of advice and knowledge and wisdom and above all, kindness.

As a result, the shop had become a mecca for all sections of society in and around Peasebrook. The townspeople were proud of their book shop. It was a place of comfort and familiarity. And they had come to respect its owner. Adore him, even. For over thirty years he had fed their minds and their hearts, aided and abetted in recent years by his assistants, warm and bubbly Mel, who kept the place organised, and lanky Dave the Goth who knew almost as much as Julius about books but rarely spoke – though once you got him going it was impossible to stop him.

Her father was still here, thought Emilia, in the thousands of pages. Millions – there must be so many millions – of words. All those words, and the pleasure they had provided for people over the years: escape, entertainment, education … He had changed minds. He had changed lives. It was up to her to carry on his work so he would live on, she swore to herself.

Julius Nightingale would live forever.

Emilia left the shop and went upstairs to the flat. She was too tired to even make a cup of tea. She needed to lie down and gather her thoughts. She wasn’t feeling anything yet, neither shock nor grief, just a dull heavy-heartedness that weighed her down. The worst had happened, the worst thing possible, but it seemed the world was still turning. The gradual lightening of the sky told her that. She heard birdsong, too, and frowned at their chirpy heralding of a new dawn. Surely the sun wouldn’t rise? Surely the world would be grey forever?