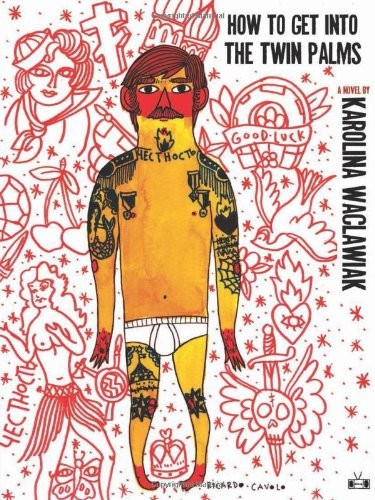

How to Get Into the Twin Palms

Read How to Get Into the Twin Palms Online

Authors: Karolina Waclawiak

Table of Contents

to my family

IT WAS A STRANGE CHOICE TO DECIDE TO PASS

as a Russian. But it was a question of proximity and level of allure. Russians were everywhere in Los Angeles, especially in my neighborhood, and held a certain sense of mystery. I had long attempted to inhabit my Polish skin and was happy to finally crawl out of it. I would never tell my mother. She only thought of them as crooks and beneath us. They felt the same about us, we were beneath them. It had always been a question of who was under whom.

as a Russian. But it was a question of proximity and level of allure. Russians were everywhere in Los Angeles, especially in my neighborhood, and held a certain sense of mystery. I had long attempted to inhabit my Polish skin and was happy to finally crawl out of it. I would never tell my mother. She only thought of them as crooks and beneath us. They felt the same about us, we were beneath them. It had always been a question of who was under whom.

I SEE A COUPLE FROM THE TWIN PALMS FUCKING

against their car across the street from my apartment. I’m hiding behind the newly purchased ficus on my balcony and watching them. I wonder if they know each other and I want to know what he’s whispering to her in Russian. I am a few feet away from them, in it with them, and I want to know if she’s a

suka

or his wife. He wouldn’t be fucking her like that if she were his wife. He grabs at her and she lets him touch her roughly and I wonder how he would touch me.

against their car across the street from my apartment. I’m hiding behind the newly purchased ficus on my balcony and watching them. I wonder if they know each other and I want to know what he’s whispering to her in Russian. I am a few feet away from them, in it with them, and I want to know if she’s a

suka

or his wife. He wouldn’t be fucking her like that if she were his wife. He grabs at her and she lets him touch her roughly and I wonder how he would touch me.

Is he a cab driver or a businessman?

He turns her around, face toward the car and pushes her against it. He moves his hand in between her legs and pulls one up around him. She doesn’t hesitate.

I whistle. He stops breathing and says something in Russian that I can’t understand. I lean forward, trying to hear better, still hidden behind the bush. It doesn’t matter. I’m not hidden enough and he sees me. The woman says something to me in Russian, spits on the ground, pulls down her dress, and pulls up her panties.

He buckles his belt. Zips. They walk quickly back to the Twin Palms and I sit outside on my balcony, hoping to see more but no one else comes out to fuck from the Twin Palms tonight.

If you walked by the Twin Palms during the day you would surely miss it. The doors are green and it looks like a rundown

relic of old Los Angeles. The sign is yellow with a drawn on palm tree. The cabs are gone and the street is empty, clean of cigarette butts.

relic of old Los Angeles. The sign is yellow with a drawn on palm tree. The cabs are gone and the street is empty, clean of cigarette butts.

I want to get inside the Twin Palms. I want them to ask me what I am. So I wait for the cabs to come back, for the Russians to swarm back like birds.

The stores on Fairfax are called

apteka

and sell prosthetic body parts and humidifiers and medicine that I have never seen before. They are next to the grocery stores that sell aging fruit and herring and halvah. I hate herring. In tubs with oil and onions, the silvery pieces curl onto each other, unmoving. I should love herring. I should love borscht. I should slurp it up with pumpernickel or rye.

apteka

and sell prosthetic body parts and humidifiers and medicine that I have never seen before. They are next to the grocery stores that sell aging fruit and herring and halvah. I hate herring. In tubs with oil and onions, the silvery pieces curl onto each other, unmoving. I should love herring. I should love borscht. I should slurp it up with pumpernickel or rye.

As I walk down the street the smell overwhelms me. The smell of rye bread and

ponchki

filled with prune jam. The yeast smell from the bakery overtakes everything and keeps it an immigrant neighborhood in Los Angeles.

ponchki

filled with prune jam. The yeast smell from the bakery overtakes everything and keeps it an immigrant neighborhood in Los Angeles.

There are Russians and Ukrainians on my street. They are not like the Russians in the Twin Palms. They wear plastic shoes and stand with their socks pulled up. The men wear shorts and their bellies hang down and out of their yellowing undershirts. The women weep. The men yell. I see them watching me through their crocheted curtains, waiting to see who comes in and who comes out of my apartment. Picking the ones I should be ashamed of.

The next night something is happening in the Twin Palms and everyone going inside is dressed in fur. I want to really see them so I lean up close to the women in their coats as I walk through and feel the silver foxes and minks brush against my cheek. The coats smell like the one my mother used to have, the one I wanted. It was a silver fox and she used to wear it all

the time in Poland when she was young. The age I am now. My grandmother had a fur too.

the time in Poland when she was young. The age I am now. My grandmother had a fur too.

A sign of a good husband in Poland is one who puts you in a silver fox – short or long. Long is better. More exclusive.

The women in the fox furs don’t appreciate how close I am to them, how my face touches the scruff of their arm. The mink of their sleeve. They curse me in Russian.

Suka.

Bitch. In Polish, bitch is

kurwa

… coorvaaah, but could also be a whore. Was

suka

a whore too? Who else but a whore would rub her cheek against their furs? I watch them walk up the stairs and want to follow.

Suka.

Bitch. In Polish, bitch is

kurwa

… coorvaaah, but could also be a whore. Was

suka

a whore too? Who else but a whore would rub her cheek against their furs? I watch them walk up the stairs and want to follow.

I round the corner and hear the sound wafting down the street.

Suka. Suka. Suka.

The women go upstairs. The men stay behind. Smoke. Snuff out cigarettes.

Suka. Suka. Suka.

The women go upstairs. The men stay behind. Smoke. Snuff out cigarettes.

I try passing again.

The men stare at me in their black leather dusters. With their Eastern Bloc homemade haircuts – a custom they never gave up in America. Hair falling in between linoleum squares, beside refrigerators, ovens, the missed unswept tufts accumulating. I catch their eyes and know they wonder what I am. If I am one of them. Most of them have gray hairs weaving through those homemade haircuts. They watch my 25-year-old ass move, tight and upright in my black stretch pants, as I walk past them slowly. I want to get up there so I walk even slower. I know what they want to ask.

Polska? Ruska? Svedka?

Or maybe just

Amerykanska.

They can’t tell with me.

Polska? Ruska? Svedka?

Or maybe just

Amerykanska.

They can’t tell with me.

They won’t ask, instead they stare; whisper something to see if I turn. Flick ash near me to see if I quicken my pace. They want to know if I’m used to men like them. I keep moving slowly because I want to see if it’s working. They look at my ass, my tits, my face last. I turn my head and stare up the stairs into the Twin Palms. The walls are mirrored and I see the women without their furs, in silk and pearls and amber, their hair in root vegetable colors, their false teeth, metal wires showing between

molars. I know some of them used to be village girls back in the old country. I can tell.

molars. I know some of them used to be village girls back in the old country. I can tell.

I lurk behind the community center and watch the cabbies start to circle again. They park. They stand outside of the Twin Palms and wait for the doors to open. They smoke. They laugh. They speak only in Russian. I stare at them and try to decide which one I would take on in order to get upstairs. They are a mix of young and old and the young look rough, like they’ve just arrived. Their leather dusters have a still-new sheen to them, bought with their first paycheck from the cabstand. Would becoming one of their girlfriends even get me upstairs?

I have to watch them closely. Who goes up. Who stays down. Who has a wife. Who is alone.

More people come. Do I want to wait for better Russians to come or should I try my luck with these? If I am going to spend my time at the Twin Palms I want it to be frequent. I want them to know me. I want to pass fully. What will my name be? I will have to change the

I

to

Y

. I will have to get my story straight.

I

to

Y

. I will have to get my story straight.

THERE ARE 20,000 BABY NAMES IN THE

book I purchased from the store that has menorahs in the window and Russian paperbacks in the back. The most popular Russian baby names are as follows:

book I purchased from the store that has menorahs in the window and Russian paperbacks in the back. The most popular Russian baby names are as follows:

Sasha – spelled Sasha and Sascha. Both make the list.

Karina

Aleksandra

Calina

Anya

Nadya

Agnessa

I wasn’t sure if the last name was a girl’s or boy’s so I cut it off the list immediately.

They were all acceptable choices – all ending with

A

and having the same Eastern European feel. I wanted my

Y

to be prominent. Anya. It could pass for Polish or Russian. I could move easily with it. Fluidly.

A

and having the same Eastern European feel. I wanted my

Y

to be prominent. Anya. It could pass for Polish or Russian. I could move easily with it. Fluidly.

I practiced speaking with an accent, but it just sounded like all the times I would mock my mother’s thick Polish accent.

Beach

sounded like

bitch

,

count

like

cunt

. I sounded like a crude caricature of her, my voice low and thick, rolling the

R

’s. I could play

her for humor but I could never be her, really. I switched back to my flat American accent and gave up. I was from nowhere and I had lived in too many places to hold on to anything permanent in my voice.

Beach

sounded like

bitch

,

count

like

cunt

. I sounded like a crude caricature of her, my voice low and thick, rolling the

R

’s. I could play

her for humor but I could never be her, really. I switched back to my flat American accent and gave up. I was from nowhere and I had lived in too many places to hold on to anything permanent in my voice.

I HAD INHERITED THE APARTMENT FROM

someone I once knew and it was strange to live here, to think about what he had done in here. The apartment was vertical blinds, beige carpets, bare off-white walls, and small things I found that people left behind.

someone I once knew and it was strange to live here, to think about what he had done in here. The apartment was vertical blinds, beige carpets, bare off-white walls, and small things I found that people left behind.

Bobby pins in the corner of the bedroom carpet, a hair ball of long blond hair in the living room that the vacuum had missed, six shrimp-flavored Ramen noodle packages at the back of the kitchen cabinet, and purple Fabuloso floor cleaner, untouched.

I used the bobby pins, threw away the hair, pushed the Ramen aside, and filled the cabinets with my own food. I threw away the floor cleaner and bought myself Ajax powder, like my mother always used.

The apartment was rent controlled so I wasn’t going to complain. But, I was curious about whose hairball was in the living room. I thought maybe some kind of actress-to-be. The roots were dark brown. She was in need of a touch-up, whoever she was, and her hair was fine, like mine.

I considered keeping the hair, saving it, but I was already holding on to too much.

SOMETIMES, WHEN THERE IS NO PARKING ON

Fairfax the Russians park on my street. The men are always alone, having already deposited their wives or significant others curbside at the Twin Palms. Alone, they like to look. I can giggle and coo here without being called a

suka

or worse,

shalava

. Here, I can woo freely.

Fairfax the Russians park on my street. The men are always alone, having already deposited their wives or significant others curbside at the Twin Palms. Alone, they like to look. I can giggle and coo here without being called a

suka

or worse,

shalava

. Here, I can woo freely.

I usually sit behind my ficus and wait. I see a few pull up with their Cadillacs and Buicks. These are better Russians. Better than the cabbies. They are well fed and wear their shirts unbuttoned two buttons to show their chest hair, their lion’s mane. I whistle from my ground-level balcony. They look for a moment, or two. I’m not their type or I’m not their girl or I just don’t work because they keep walking.

My neighbor climbs out of the sliding glass door and starts preparing something. He lays down newspaper on the table outside. He brings a floor lamp from inside the apartment outside. He brings out a few knives, and finally a fish. He smiles at me. His mustache is fine haired and ill groomed. He does not have gray yet.

He shakes his knife at me. “Do you want to take a try?” He points to the fish and smiles.

“Gut it?”

“Yes, gut and scale. Easy work.” He laughs at this but I don’t.

His English is thick with an accent. His mother still cuts his

hair in the bathroom. I can see it. The lopsided cuts. The cowlick. The telltale sign of a homemade haircut. His mother only speaks to me in Russian and I do not understand. She comes outside and smiles at me. She wants me to gut the fish and motions to it. She wants me to like her son.

hair in the bathroom. I can see it. The lopsided cuts. The cowlick. The telltale sign of a homemade haircut. His mother only speaks to me in Russian and I do not understand. She comes outside and smiles at me. She wants me to gut the fish and motions to it. She wants me to like her son.

He is much older than me. But still not old.

He lives across the street and walks back and forth. One day he talks to me – more than hello and goodbye.

“My mother thinks you’re pretty,” he says.

I stare at him. I’m not sure how to react so I smile and shrug.

“She said it. I didn’t.”

“Tell her thank you.”

I smile at her and she smiles back with her few silver teeth, just like my grandfather. Her single son climbs into her ground-level balcony every day, pulls open the sliding glass door and goes inside. A few minutes later he comes back out the front door with a small bag of garbage and brings it to the dumpster. Every day.

Why not use the front door each time? It was some kind of strange ritual I did not understand. I never considered scaling my balcony to press through my sliding glass. We were supposed to be cultured here and not do those kind of things in this country. Or call attention to ourselves. I wasn’t sure why he didn’t know that in America we used the front door, always.

My neighbor’s son doesn’t go to the Twin Palms. He walks around the streets with his white athletic socks pulled up high, and black, plastic sandals. And shorts. The men who go to the Twin Palms do not wear shorts. They wear slacks and silk shirts unbuttoned and leather jackets even if the Santa Ana winds are roaring.

Other books

[05] Elite: Reclamation by Drew Wagar

Teaching Roman by Gennifer Albin

The Charming Max by Lang, Desi

FINNED (The Merworld Water Wars) by Sutton Shields

Embracing the Unexpected by Ella Jade

Last Immortal Dragon: Dragon Shifter Romance by Joyce, T. S.

The Eye of God (The Fall of Erelith) by RJ Blain

The Death of Wendell Mackey by C.T. Westing

Kid Power by Susan Beth Pfeffer

Master of Melincourt by Susan Barrie